OM MALIK-

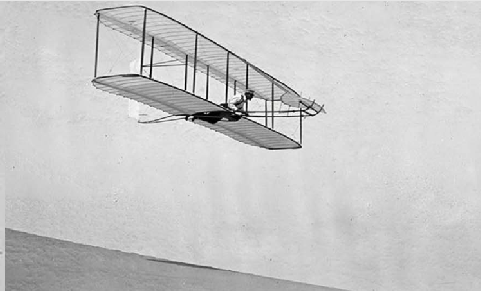

On December 17, 1903, Orville Wright piloted the first powered airplane on a beach in North Carolina. The plane ascended 20 feet above the ground and traveled 120 feet in 12 seconds, approximately 10 feet per second. On the same day, Wilbur Wright flew the aircraft for 59 seconds, covering 852 feet at a slightly faster pace of 14.4 feet per second. By comparison, the average cruising speed of a modern Boeing 737 is 756 feet per second. 120 years after their inaugural flight in 1903, air travel has become commonplace, with around 10,000 flights in the air at any given moment, carrying 1.25 million people.

In 1899, as the Wright brothers began their earnest pursuit of aviation, a group of French artists, including Jean-Marc Côté, were tasked with envisioning the distant future of the year 2000 for the 1900 World Exhibition in Paris. These visions were encapsulated in a series of futuristic images, initially lost to time but rediscovered in 1986 by author and futurist Isaac Asimov, who published them in the book “Futuredays,” A Nineteenth Century Vision of the Year 2000.

Some of those postcards envisioned concepts like “helicopters,” personal air travel, and even air warfare, long before the Wright brothers embarked on their historic maiden flight 120 years ago from today. Fast forwarding to the present, we find ourselves in an era where air taxis, flying cars, and drones are becoming as integral to our lives as airplanes were, just as imagined at the turn of the last century.

Reflecting on these historical events and predictions, I am reminded of the importance of envisioning a future — preferably a hopeful one. However, accurately predicting the timeline and eventual impact of these innovations is challenging. This perspective has consistently nurtured my optimism in science and technology. On a more prosaic level, my primary focus is on the science of technology, followed by understanding the rationale behind a technology, and then considering its societal and business impacts. This forms the basis of my “present future” framework.

Consider the concept of flying cars and air taxis, imagined in 1899. After numerous failed attempts and substantial hype from Silicon Valley, Slovakia’s Klein Vision has developed a functioning model of its AirCar. Meanwhile, Joby Aviation, based in Marina, CA, has created an eVTOL aircraft that resembles a hybrid of a quadcopter and an airplane. This represents the once science-fictional future gradually materializing in our present.

I recall my experience riding in Tesla’s first roadster, which utilized a Lotus body design. While it wasn’t the most comfortable ride, it certainly paved the way for future innovations in electric vehicles. This pioneering model even faced skepticism, notably from Jeremy Clarkson of TopGear. Fast forward to today, and it’s commonplace for me to find a Tesla as my Uber ride, illustrating the dramatic shift in the automotive landscape.

Similarly, solar power, once considered a fringe concept, has seen remarkable growth. For instance, in 2023, it was reported that China added an impressive 200 gigawatts to its solar energy capacity, showcasing significant advancements in renewable energy.

Earlier this year, I wrote:

One ground truth about modern technologies — despite all the hype and hoopla, it takes a long time for whizbang ideas to become real and widespread. We live in a networked present where the media cycle is driven by attention, and nothing begets more attention than hype and fear. Over the last year or so, “artificial intelligence” has been presented in the media as a digital voodoo man: to be feared. AI taking over the world, taking jobs, and destroying our future makes for great headlines — there is a good chance that the reality might turn out to be mundane. Sure, things can go wrong — as they do in science fiction books — but we also have no idea what benefits we might reap from the shift to this new approach to software, aka artificial intelligence.

I am choosing to adopt a more optimistic perspective, primarily due to our collective history as humans. Back in 1973, Isaac Asimov pointed out, “All technological changes meet resistance.” In one of his speeches, The Future of Humanity, he elaborated on this theme:

…all through history there had been resistance…and bitter, exaggerated, last-stitch resistance…to every significant technological change that had taken place on earth. Usually the resistance came from those groups who stood to lose influence, status, money…as a result of the change. Although they never advanced this as their reason for resisting it. It was always the good of humanity that rested upon their hearts.

For instance, when the stagecoaches came into England, the canal owners objected. Not that they would lose money, although they would, but they feared for humanity. Because as the stagecoaches tore along at fifteen miles an hour, the air whipping past the nostrils of the people on board, would by Bernoulli’s Principle, suck all the air out of the lungs.

Issac Asimov, The Future of Humanity Lecture, 1973

This notion has been repeatedly evidenced by innovations such as Apple’s iPhone, Amazon’s Cloud, Electric Vehicles, and Solar Energy. These are just some of the more recent examples. It’s important to remember the value of maintaining hope for the future — because that hope is crucial in carving out our path forward.

Now, I hope you have a clearer understanding of the common thread linking French artists, the Wright Brothers, and AI. It’s about how fringe becomes mainstream, eventually.