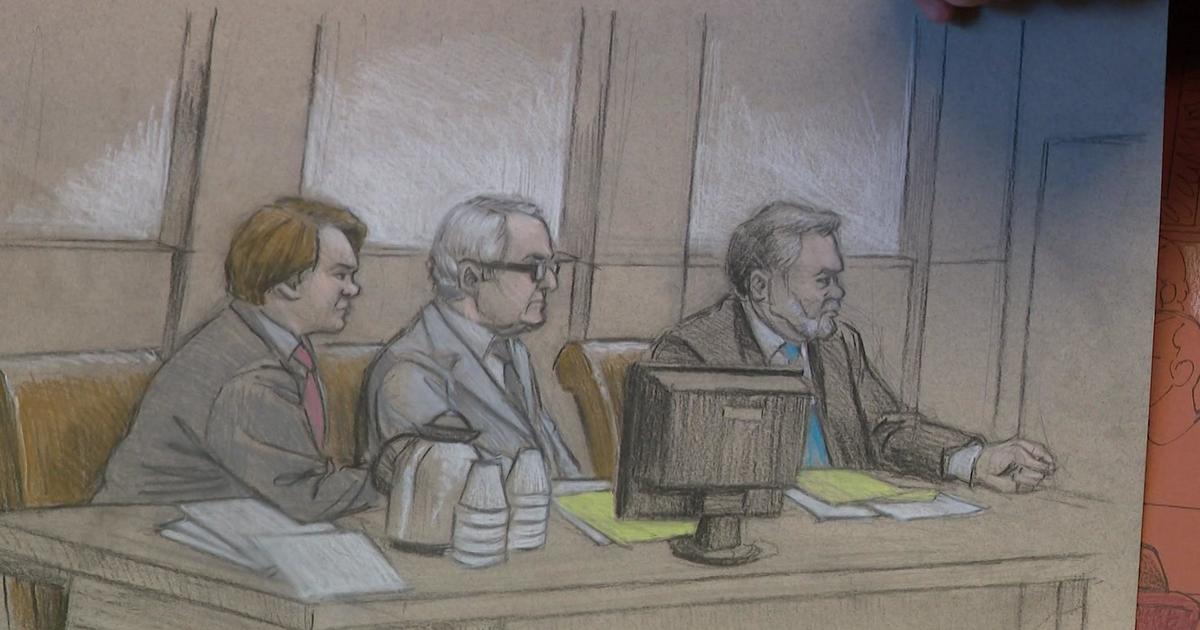

BURNSVILLE, Minn. — Cameras are appearing more frequently in courtrooms, but an age-old way to capture the moment is still finding its way into the spotlight.

Sketch artists are helping the public catch a glimpse inside Donald Trump’s trial in New York.

WCCO wanted to know: What does it take to be a courtroom sketch artist? And how is the profession changing? Good Question.

Colorful, cartoonish creativity is the hallmark of Cedric Hohnstadt’s illustration career, whether it’s drawing for a toy company like Hasbro, a children’s publisher, or even Disney.

“It’s lots of freedom to be silly and create stuff that hopefully brings joy to kids,” he said.

His side gig, however, involves capturing real-life moments in the confines of a courtroom, a job he picked up a few years after college when there was a big trial in Fargo, not far from his alma mater Minnesota State University Moorhead.

“The local media wanted a sketch artist, and they contacted the university and one of the professors recommended me,” he said.

Using his sketches from that trial, Hohnstadt pitched his skill set to media outlets in the Twin Cities, kicking off a unique journey of documenting moments in history like illustrators of centuries past.

Courtroom sketching goes back to at least the 1600s in Europe. For the United States, most notably the Salem Witch Trials in the late 1600s in Massachusetts are known as one of the first instances of trials being sketched.

A ban on cameras in the courtroom in the 1930s reinvigorated the need for sketches, leaving artists as the lone visual scribes of what happened in court for several decades.

WCCO

It’s up to the local news media to decide if a trial needs a sketch artist. Hohnstadt doesn’t work for the court system. He’s an artist-for-hire for whichever news outlet wants sketches of a trial. If he’s hired, he lets the court system know which trial he’s planning to work. Court staff then save a seat for him near the front of the gallery.

“A few things,” Hohnstadt said when asked what makes a good courtroom sketch artist. “You have to be able to draw really fast because the deadlines are tight. The news media wants something right away. Courtroom artists have to be objective and only capture what they see. They also have to convey personality, mood, and expressions. That last skill can be tough given the straight-faced feel of trials. It’s kind of like sitting in a very long school board meeting.”

He added that trials rarely carry the intensity and physical drama they do in movies and TV shows.

That’s why when a witness makes a gun gesture with their hand, or a lawyer slaps a table to make a point, Hohnstadt suddenly has interesting material to draw. The trick is memorizing the brief moment, then quickly sketching an outline to get the drawing started.

Hohnstadt averages about three to five sketches per day at a trial. It’s a range that’s easier to reach nowadays thanks to sketching on an iPad. The software on the tablet allows him to make edits, reuse backgrounds and not fumble around with colored pencils and paper. It helps him work faster and makes his job much easier overall.

More states allowing cameras in courtrooms have cut into his work opportunities, but if a judge restricts cameras, artists like Hohnstadt know their phones might ring.

He respects the public’s right to transparency, but he said there are times when cameras in courtrooms might not be a good idea.

“If someone is going to be on camera, a witness may be less likely to come forward or want to testify about embarrassing or personal things,” he said.

The few times artists still use paper and pencil are when judges ban digital devices in the courtroom. That’s because a tablet, like an iPad, could have apps that record video and audio.

To see more of Hohnstadt’s work, click here.