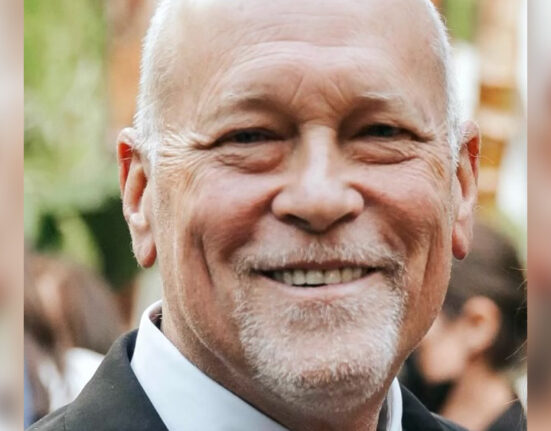

The last few years haven’t been easy for Conor Matthews. As a writer and creative struggling to make ends meet while pursuing paid work, he found himself on benefits.

He was pushed to take any job he could find and moved on to do night shifts as a porter at a hotel. The job was so draining that he had little energy left to pursue his passions.

“I was feeling extremely anxious,” he says.

Just as he felt his prospects in life were dwindling, he was handed a lifeline. The Irish government selected him as one of the participants in a basic income pilot scheme for artists and those working in the creative sector.

More than 9,000 people applied and 2,000 were randomly selected to receive €325 (£280) a week for three years, from August 2022 to 2025 – with no conditions attached. Among those selected were more than 700 visual arts, 584 musicians, 204 working in film and 184 writers. Others worked in theatre, dance, architecture.

When he got the funding, Matthews quit his job as a porter and increased the amount of time he spent on his projects from four to 20-odd hours a week. He now has agency representation and grant funding for an audio drama on Spotify.

Matthews, 34, says the past year has been the “most productive, enlightening and promising” of his life.

“It’s definitely a relief,” he says. “You just feel valued. It’s just more manageable. I’m not resting on my laurels. It’s essentially the closest you can get to saying you’re a full-time writer.”

Matthews, from Leixlip in County Kildare, is not the only creative to report a boost to their mental health as a result of the pilot scheme.

Reports published by the Irish government last month showed a decrease in anxiety and depression among recipients during the first six months of the payments. Those selected worked fewer hours in other sectors and invested more time and money into their arts practice.

As part of the pilot scheme, they have to fill out surveys with a range of questions about how they spend their time and money.

Experiences of depression and anxiety decreased by 10 percentage points when compared with the control group. Recipients were 3.6 percentage points less likely to have felt depressed or anxious “all the time” and 19.2 percentage points less likely to have difficulty making ends meet.

The scheme’s main objective was to address the financial instability faced by many working in the arts. In September 2020, the Irish government set up an arts and culture taskforce to look at how the sector could adapt and recover from the pandemic. Its top recommendation was a three-year basic income pilot.

Some €25m in funding was set aside to cover the costs. To be eligible, artists and creatives had to show they were professionals and produce evidence such as previous grant funding, exhibitions and publications of their work.

An income to replace jobs taken over by AI

Basic income trials have surged in recent years, with the pandemic proving to be a catalyst for their adoption in many countries.

Ireland is one of four internationally that focuses on artists. Other schemes have offered universal payments to everyone living in a particular area, or targeted people with specific backgrounds such as prison leavers.

Guy Standing, an economist and co-founder of the Basic Income Earth Network, says there are currently more than 150 basic income pilots and experiments taking place around the world.

Around 100 of them are in the US, but there are others in Germany, South Korea, India, Kenya and Catalonia.

Closer to home, Wales has its own government-funded scheme, with payments targeted towards care leavers. Proposals for a pilot in England were outlined last year by the Autonomy think tank, but funding is yet to be secured.

Cleo Goodman, a basic income expert at the Autonomy think tank, says: “The reason that basic income remains a compelling idea is perhaps a result of the pandemic and bigger groups of people seeing, for the first time, the gaps in the social security system and safety net that we’re supposed to have in this country.”

She says advancements in artificial intelligence have also sparked fears that jobs may be replaced by robots, resulting in mass unemployment and economic downsides.

“If we had a basic income and unconditional payment that you’d be able to depend on, regardless of your employment status, you could do meaningful and important work and have a lot more flexibility in that,” she says.

“Basic income is an opportunity to turn changes in the labour market due to AI into something that works for people and for society, rather than just for the people making the profits off of that automation.”