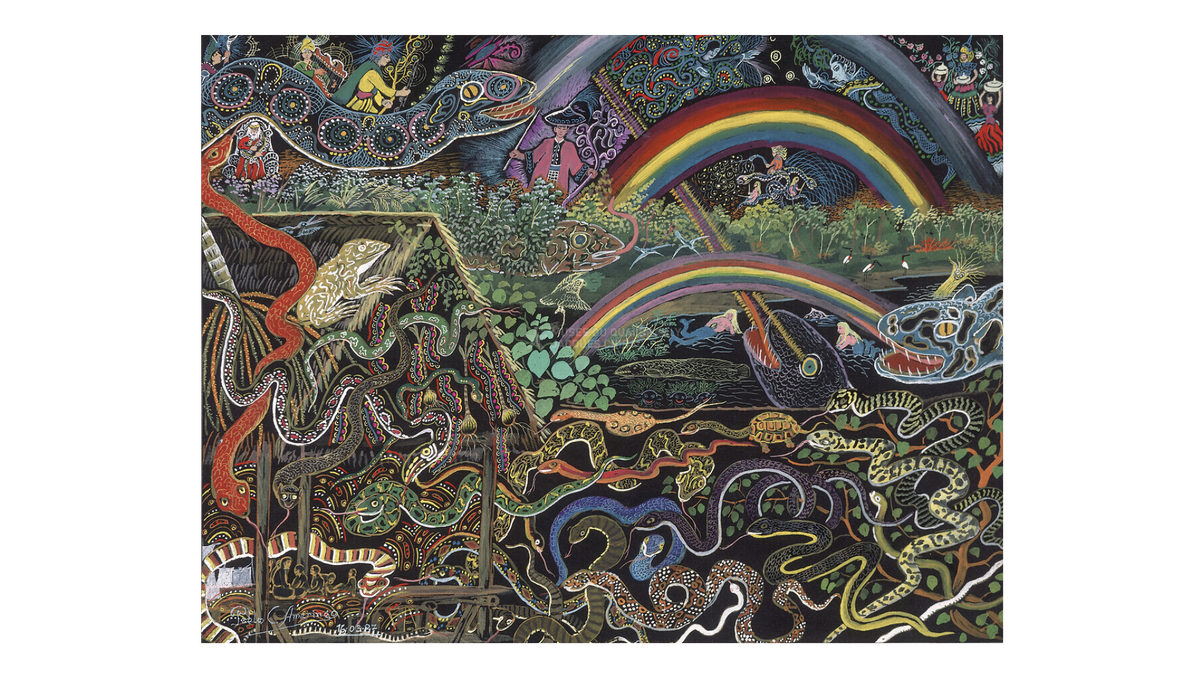

In the early 1980s, Peruvian artist Pablo Amaringo began painting the visions that ingesting ayahuasca produced in him. He did so at the invitation of Colombian anthropologist Luis Eduardo Lima, who later published a book with descriptions of the canvases. The paintings, full of colors, not only represented the fauna and flora of the Amazon, but also celestial palaces and mythological beings. The Quai Branly Museum in Paris showcases his work and that of others in an exhibition that explores the relationships between the hallucinogenic substance and artistic creation.

Ayahuasca is made from a vine, which gives its name to the brew, and the leaves of a bush called chacruna, where DMT, a psychedelic compound, is found. Upon entering the body, the substance produces alterations in perception and can cause intense emotional experiences.

The infusion is used by around one hundred communities in the Amazon rainforest for ritual and healing purposes. But it has also generated growing interest internationally, as demonstrated by research into its possible therapeutic benefits and the emergence of shamanic centers that attract a Western clientele.

The brew, also known as yagé, is prohibited in France and is in legal limbo in Spain. But in Peru, the traditional knowledge and uses linked to ayahuasca have been declared part of the nation’s cultural heritage.

“It is a topic that arouses many passions, many oppositions and tensions. I found it interesting to approach it from a different perspective, through art,” David Dupuis, anthropologist and curator of the exhibition, explains by phone. Shamanic Visions. The arts of ayahuasca in the Peruvian Amazon, is on display until May 26.

The exhibition opens with two murals painted by a local association in Lima that brings together women from the Amazonian Shipibo Konibo people. Both represent geometric shapes that resemble labyrinths of clear lines. They are the so-called kené, an iconography with multiple meanings that is also reflected in bodies, textiles and ceramics.

The designs are an integral part of the culture of these communities and are often passed down from mother to daughter. Its origins are in the worldview of this people and according to ancestral belief, they are inspired by the anaconda, which on its skin would combine all variations of motifs. But also “there is a whole series of discourses that associate kené with the [ingestion of] ayahuasca,” says Dupuis, who has been working for more than 10 years on the rise of shamanic tourism and the globalization of psychotropics.

The Shipibas Muralistas collective of Lima, for example, explains by email that the patterns come first from the piri piri plant, whose extract is usually placed with a drop in the eyes of small children. He also cites ayahuasca, which allows “visions to be channeled into designs.” The group is made up of four Shipibas artists who migrated from Pucallpa, in the Amazon jungle, to the Peruvian capital, where they have created more than 50 murals.

Not everyone claims that link. The Austrian ethnomusicologist Bernd Brabec de Mori, from the University of Innsbruck, points out by email that the designs were found on ceramics hundreds of years before ayahuasca began to be used. The reasons that are known today mostly emerged during the rubber rush, when the concoction began to be used as a means of healing. The relationship between patterns and visions dates back to “the last few decades,” says the researcher, who studied the designs for years.

What interested Commissioner Dupuis, however, is the way in which the populations of the Amazon used the attraction generated by ayahuasca as a “way of valuing” their art, their crafts and their culture. “Shipibo art and crafts achieved notoriety at the same time as shamanic tourism,” says the anthropologist.

The exhibition reveals how the kené have inserted themselves into the world art market, with artists such as Sara Flores, Chonon Bensho or Celia Vasquez Yui. The three live in Peru, but are part of the Shipibo Conibo Center in New York, a non-profit organization that seeks to enhance their creations, now on display in Paris. But the exhibition also includes works that break with the tradition of the kené and opt for a more figurative register, always related to the mythology, environment and ways of life of the Amazonian communities. And sometimes, with ayahuasca-induced visions.

Shipibo-Konibo painters

This is the case of Pablo Amaringo, who together with the Colombian researcher Luis Eduardo Lima created the Usko Ayar painting school in the Amazonian city of Pucallpa in 1988. Or Roldán Pinedo, who is part of the first generation of Shipibo-Konibo painters who emigrated to Lima, among others, to publicize their creations. Of his painting “The Vision of the Rainbow,” he says: “It is an illustration of the world that is in the rainbow, which I saw during an ayahuasca ceremony. Painting that vision seemed like evidence to me.”

Through art, the exhibition also seeks to reflect on the globalization of the brew, driven by the rise of shamanic tourism. Popularized in 1963 by writers William Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg with Yagé Letters, the growing interest in this hallucinogen has generated profound cultural and economic transformations in the area. And it has opened the way to the emergence of another, more psychedelic form of art.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition