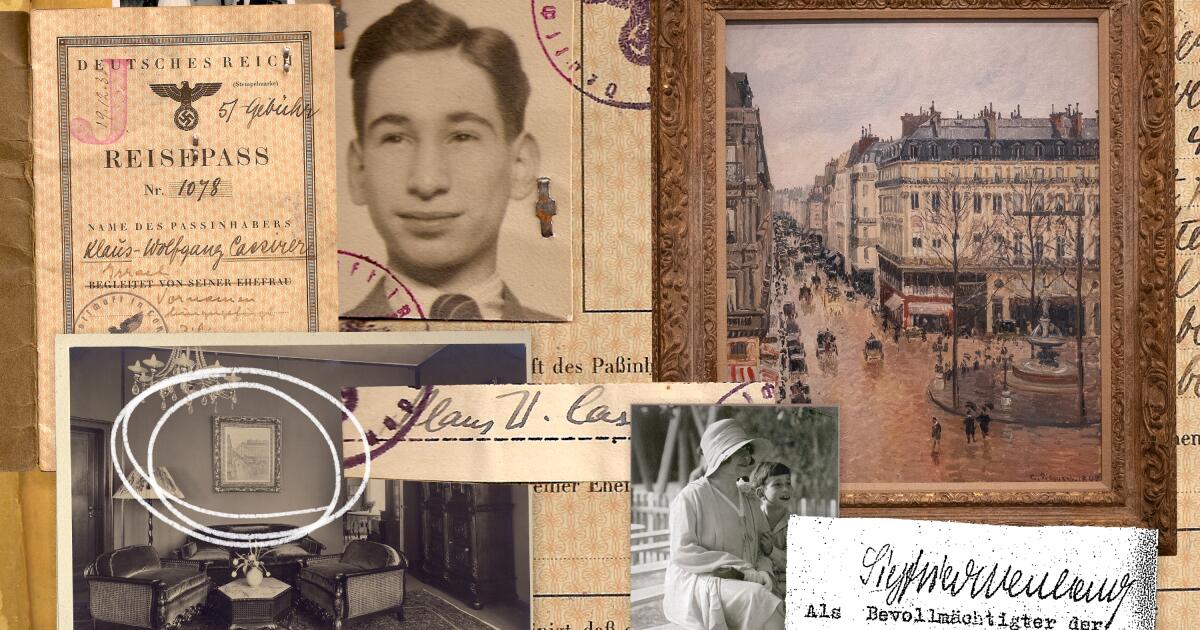

It was early 1939 and the window for Jews like Lilly Cassirer Neubauer to escape was rapidly closing. The Nazis had been tightening their grip on Germany, ransacking synagogues and Jewish homes and schools. Death camps would follow soon.

In desperation, she surrendered an exquisite impressionist painting in her family’s art collection for a visa to flee Germany at the dawn of World War II.

Six decades later, Lilly’s grandson in San Diego made a shocking discovery: the painting had resurfaced in Europe, tied to the scion of a German industrialist family that helped finance Adolf Hitler’s rise to power.

Today, Lilly’s great-grandson David Cassirer awaits a decisive ruling in the family’s long legal battle to reclaim the painting, now in a Spanish museum. The work by Camille Pissarro is estimated to be worth tens of millions of dollars.

The fight isn’t only about money, but family legacy and a conflict between law and morality.

From the early 1930s until the war’s end in 1945, the Nazis stole an estimated 650,000 paintings and other artworks. Many have never been found, while legal battles for others rage on. Each family’s case is different, but a decisive legal victory for one often benefits many, and Jewish families, restitution experts and attorneys the world over have been watching the Cassirer case closely for decades.

Thaddeus Stauber, an attorney for the museum, declined to comment on behalf of his clients.

Cassirer — now 69, of Colorado — said he wants to see the case to the end for his great-grandmother, who lived with his family in the U.S. for several years before her death in 1962, and his father, Claude, who died in 2010 dreaming of the painting’s return.

“As a Holocaust survivor, my father never stopped thinking or talking about what happened to the Cassirers and to the Jewish people in Europe during the Nazi era,” Cassirer said. “His quest to recover the [painting] was the embodiment of the seemingly impossible dream of restoring at least something of what the Nazis had so brutally destroyed.”

Escaping the Nazis

Before the war, the Cassirers were wealthy art collectors, gallerists and publishers who helped put promising artists — including Jewish impressionist Pissarro — on the map. The family’s Berlin gallery was famous in the art world.

Lilly joined the Cassirer family by marrying the opera conductor Fritz Cassirer. They had one child, Eva, who later gave birth to David’s father, Claude. When Eva died of the flu in 1921, Lilly became one of Claude’s primary caregivers.

A photo of Claude Cassirer as a young boy with his grandmother, Lilly Cassirer, who was forced by Nazis to surrender a precious Pissarro painting in exchange for a visa to flee Germany at the dawn of World War II.

(The Cassirer Family Trust)

In 1924, Lilly and Fritz inherited what she later called an “heirloom” from her late father-in-law: an 1897 Pissarro painting in a golden frame depicting a glistening Parisian streetscape, titled “Rue Saint-Honoré in the Afternoon. Effect of Rain.” The painting had been in the family since about 1900, according to court records. In 1926, when Fritz died, Lilly became its sole owner.

While she also had other valuable art — a Jacob van Ruysdael landscape, a Degas bronze ballerina — the Pissarro was special: A photograph from the time, taken for insurance reasons, shows the Pissarro hanging at the center of the family’s Berlin parlor.

In 1938, the Nazis entered Austria. In January 1939, Lilly — by then living in Munich — married Otto Neubauer, a prominent doctor who had been forced by the Nazis to give up his position as head physician at a Munich teaching hospital. That March, the Nazis took Prague.

Desperate to escape, Lilly paid what amounted to a Nazi ransom.

At the time, Jewish families of means were still able to secure exit visas by allowing their estates to be assessed by Nazi appraisers, who took what they wanted and charged an exorbitant “flight tax” on anything the families took abroad.

The families were sometimes paid nominal cash amounts, as the Nazis feigned administrative legitimacy for their systematic theft of Jewish wealth, but the same families were precluded from taking cash out of the country.

Jakob Scheidwimmer, a local art dealer and Nazi party member, appraised the Pissarro and decided to take it. He paid 900 Reichsmarks, a fraction of the painting’s worth, into an account Lilly couldn’t access. She got her visa, and the couple fled to England.

That September, the Nazis invaded Poland and the war officially began. Many Jews who hadn’t already escaped perished in Nazi death camps, including Lilly’s sister and mother in Auschwitz, the family said.

Jonathan Petropoulos, a prominent expert in Nazi-looted art who has worked on the Cassirer case for two decades, said Jews like Lilly faced sheer terror and lacked leverage when confronted by practiced Nazi appraisers such as Scheidwimmer.

“For Lilly, history was telling her to get out of the country as quickly as possible,” Petropoulos said, “and she was dealing with a shark.”

A hunt across continents

Lilly never forgot the Pissarro, and neither did her grandson Claude.

Around the same time Lilly was making her escape from Germany to England, Claude was in France, where he’d unwisely traveled with a friend from school in England, his son said.

“My father always said it was to learn to speak French better,” Cassirer said, “but you can bet they were chasing girls.”

Claude, then still a teenager, was detained by France’s Nazi-collaborationist Vichy government and held in a camp in the Moroccan desert outside Casablanca, where he contracted typhoid fever and nearly died, his son said. He was rescued when Allied forces advanced into North Africa, and he eventually boarded a ship bound for the U.S.

He convalesced at a hospital in New York before moving to Cleveland, where he married a local girl named Beverly and became a photographer. Claude remained close with Lilly. She had started looking for the painting after the war, hiring a lawyer in Germany and identifying herself to the postwar government as being owed restitution for the theft.

Beverly Cassirer and her husband, Claude Cassier, both now deceased, at their home in San Diego. A copy of the Nazi-looted painting they wanted returned hangs behind them.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

In a December 1948 government claim, Lilly wrote that she believed the painting had fetched 85,000 Reichsmarks at a Berlin auction soon after Scheidwimmer had taken it, and that the incident constituted a “major confiscation,” according to a translation of the document filed in U.S. court.

Lilly’s claim led to a drawn-out court battle in Germany, complicated by the fact that Scheidwimmer had “traded” it to a second Jewish family before it was confiscated by the Nazis again. In 1958, the parties agreed to a settlement: Germany paid Lilly 120,000 Deutschmarks, or about $250,000 today, according to one court estimate, with a portion of that earmarked for the second Jewish family.

“Rue Saint-Honoré in the Afternoon. Effect of Rain,” 1897, is in the Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection in Spain.

(Heritage Images / Getty Images)

Cassirer said the family never thought the settlement ended their claim. Lilly left the rights to the painting to Claude when she died, and Claude never stopped wondering about its whereabouts — or mentioning it to friends. For all he knew, it had been sold at a Nazi auction, then vanished.

Then one day in late 1999 or early 2000, he received a call from Anne Groves, an artsy friend in New York.

Groves, now 88, said in an interview with The Times that she had been clearing books from her living room to prepare for house guests when she noticed an old book on Pissarro that listed many of his paintings and their locations around the world.

“It was just an accident that I found it,” she recalled — but a lucky one. She phoned Claude.

“She wanted to know if, by any chance, one of those paintings was the one that had been looted by the Nazis,” Claude said during a 2006 court deposition.

Claude immediately faxed a copy of an old black-and-white image of Lilly’s painting to Groves, who told him she thought it was a match for one of the paintings listed.

An old insurance photograph shows the Pissarro painting hanging in the Cassirer family’s home in Berlin in the 1920s.

(The Cassirer Family Trust)

When Claude got his hands on his own copy of the book, he said, he instantly realized she was right.

“It said that the painting was owned by Baron von Thyssen,” he said, “and that it was in Lugano, Switzerland, where the baron lived.”

The baron: A sophisticated collector

Baron Hans Heinrich von Thyssen-Bornemisza — who went by Heini — was born in the Netherlands, held Swiss citizenship and lived for tax purposes in Monte Carlo, but his fortune was from German iron and steel.

Thyssen-Bornemisza’s grandfather August Thyssen had founded a steel mill in a German industrial district and amassed a fortune, which he passed on to his sons when he died in 1924.

Heini’s uncle Fritz Thyssen used part of that wealth to finance Hitler’s rise, though he later denounced his Nazi affiliations. Heini’s father, Heinrich Thyssen, moved to Hungary and married the daughter of a baron, who had no sons of his own and adopted Heinrich. Heinrich took up the hyphenated name Thyssen-Bornemisza, and his father-in-law’s title.

Heinrich later moved to Holland, where he used his inherited fortune to branch into shipping and banking. He eventually settled in a palatial mansion called Villa Favorita on the shores of Lake Lugano in Switzerland, which he’d acquired in 1932 from a Prussian prince, and began to build an impressive art collection with works of old masters.

Industrialist and art collector Baron Hans Heinrich von Thyssen-Bornemisza (1921-2002) in 1988.

(Georges De Keerle / Getty Images)

Under Heini’s leadership, the Thyssen-Bornemisza Group further diversified into other industries. As he amassed an ever-larger fortune, his private art collection became second only to the British Royal Family’s, according to various accounts published around the time of his death in 2002.

Well in the garden of Villa Favorita, 17th century, Lugano, Ticino, Switzerland.

(DEA / G. SOSIO / De Agostini via Getty Images)

In 1976, the baron purchased four pieces of art from the Stephen Hahn Gallery in New York, according to experts for the Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection. One of them was the Pissarro, which had a cloudy history between the end of the war and its arrival in the U.S.

In July 1988, Architectural Digest featured Villa Favorita in a large spread that detailed the stunning scope of the baron’s art collection and included photographs of some of its most precious pieces. One showed Lilly’s painting hanging in the baron’s private dressing room.

The article said the baron was “constantly juggling proposals that come to Lugano from all over the world to help him decide the future of his collection.”

Soon enough, he accepted one.

In 1993, the baron sold 775 works to the Kingdom of Spain — the native land of his fifth and final wife — for $350 million. Spain put another $45 million into renovating an early 19th-century palace near the Prado Museum in Madrid to house and showcase the collection, which became a major tourist attraction: the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza.

Heini was still alive when Claude found Lilly’s painting in the Pissarro book, but not when the lawsuit was filed in 2005, leaving a key question unanswered: What did he know of the Pissarro’s tainted history when he bought it?

A ‘good faith’ buyer?

Cases involving Nazi-looted art are rarely cut and dried. Many hinge on the pieced-together stories of a generation of Jews — now almost entirely lost — whose households and family records were destroyed by the Nazis.

The Cassirers’ case is special in part because “Lilly got out with all of her trunks full of pictures and documents,” her great-grandson said. “Soon after, nobody got out.”

Special, however, doesn’t mean simple. The case has raised complex legal questions, forcing judges to reconcile conflicting statutes from different territories.

In California, thieves cannot pass good title for stolen property on to subsequent buyers. In Spain, buyers can gain good title eventually if they purchased the item in good faith — that is, they didn’t know it was stolen when they bought it — and then possess it for a certain number of years without challenge.

The Cassirers maintain that the baron and the museum knew or should have known the painting was looted, and have an obligation to return it. The museum says it didn’t know and maintains its title as a good-faith buyer under Spanish law.

Both sides have hired experts with impeccable credentials to back their positions.

Petropoulos, a professor of European history at Claremont McKenna College, has worked on the subject of Nazi looted art for more than 40 years and is the author of several books on the topic, including “The Faustian Bargain: The Art World in Nazi Germany.”

A woman looks at the impressionist painting “Rue St.-Honore, Apres-Midi, Effet de Pluie” painted in 1897 by Camille Pissarro, on display at the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum in Madrid in 2022.

(Manu Fernandez / Associated Press)

He argued, on behalf of the family, that the baron and the museum’s experts would clearly have known the painting was looted — or at least that it was suspicious and warranted further investigation — given the gaping holes in its ownership history after the war and a partial Cassirer Gallery label on its backside.

Petropoulos said the baron was one of the world’s most sophisticated art collectors, and should have known how to identify stolen art. He had other experts working for him, but often took a personal interest in the paintings he acquired, Petropoulos said, and was keenly aware of the sensitivities involved as the scion of a German family with embarrassing Nazi ties.

Lynn H. Nicholas, who similarly has studied Nazi looting for decades and is the author of “The Rape of Europa: The Fate of Europe’s Treasures in the Third Reich and the Second World War,” served as an expert for the museum — and argued the opposite of Petropoulos.

Nicholas said information about the Cassirer family’s ownership and Lilly’s forced “sale” of the painting to Scheidwimmer was not readily available at the time of the baron’s purchase in 1976 or the museum’s purchase in 1993. She said there were no “red flags” about the painting’s provenance.

In 2019, U.S. District Judge John F. Walter ruled otherwise, deciding that the baron should have taken added steps to investigate its history before purchasing it. However, Walter also found no proof that the baron or the museum had “actual knowledge” that the Pissarro was stolen, and therefore the museum’s title to the painting was valid under Spanish law.

Walter noted that Spain had signed multiple international agreements for the return of Nazi looted art, but wrote that he could not force the country‘s government “to comply with its moral commitments.”

Over the years, attorneys for the Thyssen-Bornemisza museum have downplayed the harrowing nature of Lilly’s ordeal. They have suggested the Pissarro was sold — not stolen — as part of a deal in which Scheidwimmer helped get Lilly out of Germany with other precious art. They have argued that a restitution payment Lilly received from the post-war German government, in the 1950s when the painting was still missing, resolved her claim to the painting.

The Cassirer family, their attorneys and Jewish organizations say those arguments have not only been rejected by the courts, but are insulting — trading on the dangerous stereotype of Jewish greed by suggesting the family is looking to be paid twice.

‘Contrary to common sense, and common decency’

In 2021, the legal dispute reached the U.S. Supreme Court. The Cassirers argued the lower courts had wrongly applied Spain’s law rather than California’s, and the following year the high court agreed, sending the case back to the U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals for reconsideration.

Cassirer was bullish about the family’s chances. Then, in January, the 9th Circuit found that even California’s law required deference to Spain, and Spain should retain the painting.

One of the three panel judges who made the decision — Circuit Judge Consuelo Callahan — said it was correct legally but went against her “moral compass.”

On its website, the museum says the case is closed and lists the painting as part of its permanent collection.

But Cassirer said the family remains hopeful, and has asked a larger, 11-judge en banc appellate panel to consider the case. A win for the family, he said, would put plunder holders around the globe on notice and help other families fighting to reclaim stolen property.

A coalition of prominent Jewish groups and legal organizations also has called for reconsideration, arguing in its own recent filing that the ruling in favor of the museum perpetuates “Holocaust minimization” and “turns the horrors of Nazism into an ordinary business transaction.”

“Such a legal result cannot stand,” the coalition wrote. “Nazi looted art is stolen property and forever tainted until returned to those from whom it was stolen or their heirs — full stop.”

Cassirer said he doesn’t understand why the Spanish government or such a prominent art museum would want to own a painting that was stolen from Jews fleeing Nazi death camps and never returned.

“Spain’s behavior for nearly 25 years, since we first approached them to recover our family’s priceless heirloom, is so very clearly contrary to common sense, and common decency,” he said — what Jews of his father’s generation in Europe would call a “shanda,” or a deep shame in Yiddish.

David Cassirer, the great-grandson of Lilly Cassirer Neubauer, poses for a photo outside the U.S. Supreme Court in Washington in 2022. Lilly surrendered a Pissarro painting to the Nazis in exchange for safe passage out of Germany at the dawn of World War II, and David is fighting for its return.

(Susan Walsh / Associated Press)

He still hopes the painting will be returned, he said. If it is, the next steps are “already cast in stone.”

“My father had very specific wishes,” Cassirer said, “and I’m loyal to my father, who was good to me.”

After selling the painting at auction and paying off attorneys fees and other obligations, Cassirer said he would establish and run a foundation designed to help other families in need and support civil rights groups and other organizations important to his parents.

Those who have had art and other property looted from them would be “high on the list” of the foundation’s priorities, he said.

“It’s crucially important that nobody gets to keep anything that was stolen by the Nazis from Holocaust victims,” Cassirer said.