Courtesy the Met

The Metropolitan Museum of Art is doing so many interesting things right now—a “Manet/Degas” doubleheader, a sprawling Jacolby Satterwhite commission, and a show about Africa and the Byzantine Empire, to name just three—that it is easy to forget the most exciting one of them all: a sweeping rehang of its European paintings galleries.

In 2018, these galleries started to shutter as the Met revised their skylights. With a cost of $150 million, the initiative is the largest capital project ever undertaken in the museum’s history. The gamble paid off: more natural illumination now flows into the galleries, which began reopening in 2020 and are now, at long last, completed.

When those galleries started the slow process of reopening during the height of the pandemic, new focuses emerged. Women artists, who had historically been all but shut out of the European painting department’s presentations, were given greater attention, and so were topics like colonialism, class, race, and gender. Now, the curators have delved even further into the process of editing a canon that went stale.

Starting today, visitors will be able to see all of the European painting galleries for the first time in half a decade. They look better than ever, and there is plenty to see—nearly 700 works are parceled across 45 beautiful spaces, many of which are shorn of walls that previously caused them to feel cloistered and hermetic.

Old friends return anew. All five of the Met’s Vermeers are afforded their own space all to themselves; they’re back after a sojourn in a sad special exhibitions space while the galleries underwent renovations. A host of works by Francisco Goya, Peter Paul Rubens, and Jacques-Louis David are here, too, along with many other jewels of the Met collection. But rather than simply offering these treasures once more, the curators, working under the leadership of department head Stephan Wolohojian, have sought to view them through fresh lenses.

Work by the German Expressionist Max Beckmann hangs beside an altarpiece by Jean Bellegambe, an artist associated with 16th-century Flanders.

Courtesy the Met

Take the Giovanni Battista Tiepolo showstopper that has long greeted viewers to these galleries, an 18-foot-tall history painting called The Triumph of Marius (1729). Its title asserts its main character as the Roman general Marius, but one’s eye falls on Jugurtha, a North African king who, after being captured by the Romans, was chained up and paraded through the streets. It’s a violent spectacle that seems at odds with the majesty of Tiepolo’s rendering, filled as it is with waving flags and clustered onlookers, and the curators don’t entirely let him off the hook.

They’ve placed The Triumph of Marius beside a ca. 1764 lacquerware tray by José Manuel de la Cerda, a Purépecha painter in Mexico whose representation of an episode from Virgil’s Aeneid is encircled by racing horses and winding trees, all done in a style borrowed from Asian decorative objects. Admittedly, the Tiepolo and the de la Cerda don’t have much in common, beside the fact that they turn to ancient Rome for inspiration. But the point remains: both Tiepolo and de la Cerda were working in a Europe that had already been globalized, with the tendrils of its empire reaching all corners of the world via colonialism. A nearby gallery called “Tiepolo and Multiracial Europe,” featuring oil sketches depicting enslaved Venetians and personifications of Africa and Asia, only confirms that.

This is a permanent collection hang that boldly expands the very concept of European painting and sculpture. European Paintings is a common department name in many Western institutions, but it is something of a misnomer, the Met curators seem to say, because the continent’s influence extended across the Atlantic and even toward the Pacific.

An entire gallery of the European paintings galleries at the Met is devoted to the art of Spanish America. At center is Our Lady of Valvanera (ca. 1770–80), by an unknown Cuzco painter.

Courtesy the Met

A gallery devoted to the art of Spanish America proves the point. With a range of pieces produced in Mexico, Guatemala, Peru, and elsewhere, it features a ca. 1770–80 work by an unknown Cuzco painter that shows a sculpture of the Virgin Mary. This figure, known as Our Lady of Valvanera, was thought to have been hidden in a tree in Spain’s La Rioja region until it revealed itself in a vision to a thief, who, in this work, is shown kneeling beneath her. The painting, with its craggy Iberian peaks, speaks of an inseverable connection to Spain, which had colonized Peru more than two centuries earlier.

Hieronymus Bosch’s The Adoration of the Magi (ca. 1475) is exhibited with a focus on the Black king at right.

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Elsewhere, there is an emphasis on Black and Brown figures who had previously been downplayed in these galleries. There’s a William Wood portrait of the Bengali nursemaid Joanna de Silva in a gallery titled “The British Atlantic World,” and a painting of Saint Maurice, a North African commander of the Roman legion, by Lucas Cranach the Elder and his workshop in a space about the Northern Renaissance. There’s even a Hieronymus Bosch painting of the Adoration of the Magi whose wall text centers around a Black king observing the proceedings.

This presentation does not wipe the canon clean—not entirely, at least. Even if certain thematic galleries wrest portraits and landscapes from the rigid grouping by nationality that had previously structured the galleries, much of what is on view still proceeds as it did before, now with a chronological orientation. The offerings run from Gothic Italy through Baroque Spain, from the Dutch Golden Age to Neoclassical France.

That is not to say that there are no fireworks along the way. In a touch that feels quietly revolutionary, women artists begin to take center stage by the end.

Margareta Haverman‘s A Vase of Flowers (1716) is among the many works by women that have entered these galleries.

Metropolitan Museum of Art

The star of the still life galleries is not Willem Claesz Heda, whose vanitas scenes feature tables laden with the remains of picked-over feasts, but Margareta Haverman, a Dutch painter who succeeded him. Her work A Vase of Flowers (1716), featuring roses and hydrangeas that are so bountiful as to nearly conceal the vessel which holds them, is something to behold. It is painful to learn that this is just one of two known paintings by her that remain. And in the French galleries, there’s a relatively new acquisition, Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun’s Julie Le Brun (1780–1819) Looking in a Mirror (1787), a painting of the artist’s daughter contemplating her own image. As this little girl peers into her glass, her reflected gaze meets the viewer’s.

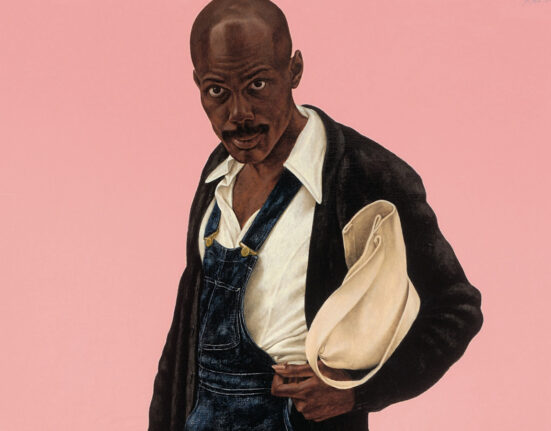

Then, in a moment that feels like a true shocker, the curators bring things into the present. One of the final galleries of the European wing features a good deal of contemporary art. Self-portraits by the 18th-cenutry Frenchwoman Marie Victoire Lemoine and the 20th-century American Abstract Expressionist Elaine de Kooning are presented side by side, implying that women artists have been representing themselves for many, many years, even when no one took notice. An 1817 Jean Alaux painting of the artist Léon Pallière shares space with a 2014 Kerry James Marshall canvas in which all the figures—both the painter and his models—are Black.

Kerry James Marshall’s Untitled (Studio), from 2014, is among the contemporary artworks that have joined the European paintings galleries.

Courtesy the Met

Perhaps even more jolting is a gallery that divines connections between El Greco and European modernism. Set aside a few minutes to observe El Greco and Paul Cézanne’s views of Toledo and Fontainebleau, respectively. Few will regret pausing to compare the fractured planes of the Spaniard’s cramped hills and the Frenchman’s uneven rocks. Leave it to the Met to find a new take on a topic that’s grown old hat.

But these are the flashiest gestures in galleries that largely do not make much of their greatness. And so, some of the true revelations can get lost in the hustle. Here’s one: Pierre Jacques Volaire’s ca. 1776 painting The Eruption of Vesuvius, A View of Naples Beyond, in which a group of awestruck people cower beneath a blast of molten rock. The lava spews into the night sky, disrupting the serenity of the moonlit clouds above. The Volaire painting is a new one to the Met’s galleries—it was promised as a gift to the museum this year. Consider that a reminder that the museum likely has many more surprises in store for the years to come.