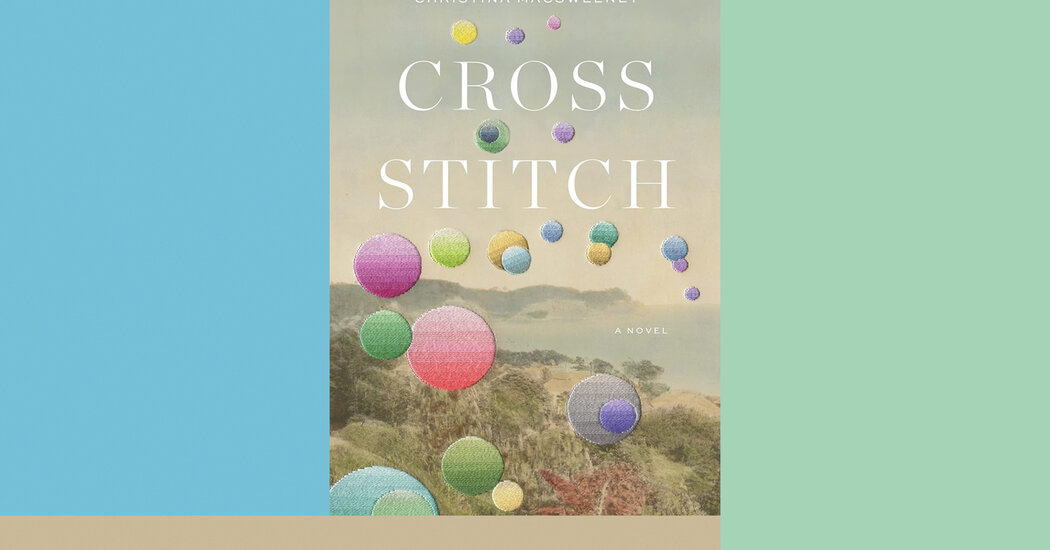

CROSS-STITCH, by Jazmina Barrera. Translated by Christina MacSweeney.

Needlework is often depicted as a peaceful activity: feminine, unthreatening, decorative. Yet in Jazmina Barrera’s understated and lovely debut novel, “Cross-Stitch,” translated from the Spanish by Christina MacSweeney, embroidery is revealed to be as quietly brutal as young womanhood, despite the shroud of innocence society often places over both.

Mila is an author, mother and needleworker whose life with a young child and a new book is so all-consuming she scarcely has time to attend to the growing patch of mold on her bathroom ceiling, let alone think about her adolescent best friends, Dalia and Citlali. That changes when Mila receives a Facebook message from Citlali’s aunt informing her that Citlali has drowned off the coast of Senegal. Citlali’s aunt asks her to help plan the funeral, which Mila agrees to, but the news also sends Mila reeling into her memories — she begins to recall a life-changing trip to Europe with Dalia and Citlali, as well as their other teenage escapades across their home of Mexico. Through her reflection she slowly realizes that in their teenage years, while she and Dalia were crafting themselves into independent adults, Citlali was starting a slow unraveling that would culminate in her mysterious death abroad.

As teens, the trio were unlikely friends. Dalia was gorgeous, adventurous and erudite. In middle school, she surrounded herself with “the sporty types, the good-looking girls who were no longer little kids, who played soccer or volleyball in the afternoons, had boyfriends, wore low-cut tops and could dance.” Citlali, however, seemed to reject the concept of cool as an identity. She was known for her raucous laughter, which “cackles like thunderclaps exploding from her wide mouth, often followed by an attack of hiccups,” Mila thinks. “She’d laugh at anything and anyone, herself most of all.”

The two go on opposite journeys in Mila’s memory and as the novel unfolds: While Dalia’s intensity, intelligence and sexuality continue to deepen over the course of the book, Citlali’s exuberance and humor fade, replaced instead with insecurity and rage. As the sparkle drains from Citlali, so does the fat on her bones, with Dalia and Mila nervously noticing that she eats less and less.