Exterior Panorama, Metropolitan Museum of Art (photo by Michael Gray, via Michael Gray’s Flickrstream)

Our encyclopedic museums like the Metropolitan Museum of Art are vocally committing themselves to diversity and inclusion, and enacting major changes to the way they tell the story of world art. In many ways, however, Europe is still firmly fixed at their centers. I work in a large encyclopedic museum, where I curate shows and displays in a collection of European art. Amidst a surge in white supremacist violence in my community and across the country, I believe the time has come to reconsider how American museums are presenting European art.

European painting and sculpture has formed the core of our museums since they were founded. These works usually inhabit the largest and most central galleries in buildings that are themselves European in style, modeled after the great royal and imperial collections of England, France, and Germany. Because the centering of Europe is baked into the architecture of these institutions, some may not see the connection to white supremacy today. But white supremacists do. Europe’s cultural prestige is their evidence for the racial superiority of white America.

#Whitenationalists and American #NeoNazis want the rest of us to see them as legitimate social and political movements

Beware of #Greeks Bearing Gifts: How Neo-Nazis and Ancient Greeks Met in Charlottesville | https://t.co/hXsbHuKxXk pic.twitter.com/HzKr964XKl

— Origins (@OriginsOSU) July 22, 2018

Consider the recruitment materials that white supremacist groups distribute. One video starring Richard Spencer cycles through images of European paintings and monuments as he intones: “We aren’t just white. White is a checkbox on a census form. We are part of the peoples, history, spirit, and civilization of Europe.” Joining Spencer at the 2017 Unite the Right Rally was the white nationalist group Identity Evropa. They assert the superiority of “European, non-Semitic heritage” and advocate ending immigration to the United States to maintain the “European-American supermajority.” They recruit primarily on college campuses and use imagery of Renaissance sculptures emblazoned with calls to “Protect your heritage” and “Serve your people.” A March 2018 rally on the steps of Nashville’s replica of the Parthenon featured a 40-foot banner: “European Roots/American Greatness.” Far-right Twitter and Reddit also proudly claim 19th- and 20th-century European art, but tend to lose interest around the end of the Second World War. As neo-Nazi site The Daily Stormer tells it, with the Allies’ victory, “the West’s cultural evolution was also completely upset. In practically every way, the art produced today is inferior to European art thousands of years old.”

In the cities where today’s white supremacists are organizing, museum galleries are the places where Europe’s cultural patrimony is most visibly singled out as exceptional. The white supremacists have noticed. In February of last year, one group gathered at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. Lingering in a room of 18th-century French armchairs and English landscapes, they were confronted by anti-fascist activists, then threw punches and were ejected. They had come to the museum for a “white lives matter” rally. Organizers later explained that they chose that location in order for participants to “enjoy the Minneapolis Institute of Art’s collection of traditional art.”

This history is long and our response overdue. Activist campaigns from the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition to the Guerilla Girls and more recently LaTanya Autry and Mike Murawski’s “Museums Are Not Neutral” and MTL+’s “Decolonize This Place” tell it plainly: America’s encyclopedic museums originated from worldviews not that different from those of today’s white supremacists and nationalists. With few exceptions, our museum founders sought to establish America’s inheritance of European empire and to “civilize” America’s immigrant and working classes.

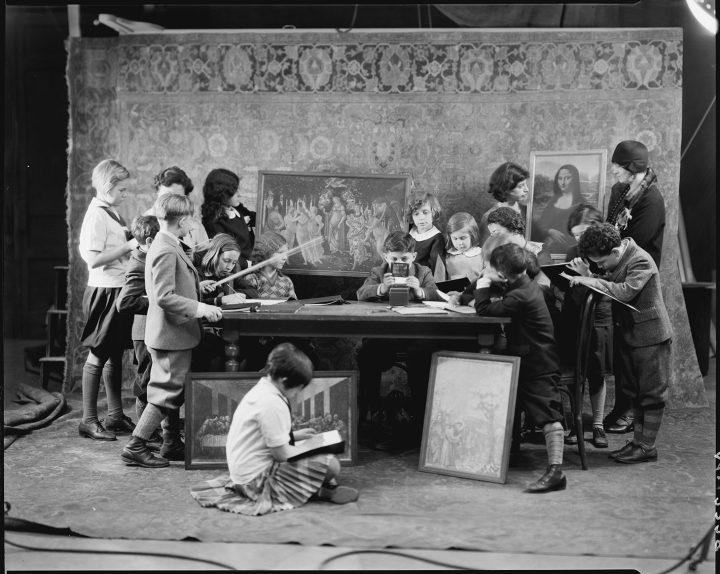

“Class of Members’ Children” (1929) (photo © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, via The Metropolitan Museum of Art Flickrstream)

At the opening of its first neo-Classical style building in 1888, Metropolitan Museum of Art trustees announced their mission: “To provide instruction for the industrial classes … With the best specimens of the Renaissance and Louis 16th, we can bring our artisans up to the best work of foreign manufacturers.” The Met’s vice president, William Prime, foresaw the museum’s role in building America’s future as the “noblest development of humanity” and compared its “exalted civilization” favorably to Ancient Greece and Renaissance Europe. “I have seen finer American horses than those horses of Phidias. There are nobler forms of men than Praxiteles ever sculpted. There are fairer women here to-day than Titian ever painted — lovelier than Raphael ever dreamed of.” If they also showed the arts of China, Japan, Persians, Assyrians, Egyptians, ‘Hebrews,’ it was because they were the “record of characteristics of a people, a race, an age” that offered lessons for the improvement of American civilization.

Today, the leaders who oversee these museums are distancing them from these founding visions. Max Hollein, taking directorship of the Met this summer, described it as “an encyclopedic museum at a very, very challenging, probably volatile moment.” He added, “Encyclopedic museums were founded on the idea that you bring the culture of the whole world to one place and tell one single narrative.” Citing “the buzzwords, globalization, interconnectivity,” he explained, “the idea that you can actually tell one succinct story is really impossible. You have to be an institution that embraces diversity — another buzzword — not only regarding your staff and collection but in terms of the multiple narratives you provide about the cultures of the world.”

“Globalization,” “interconnectivity,” and “diversity” are more than museum “buzzwords”; they are the battles white supremacists are fighting. Thankfully, the Met and other major encyclopedic museums are enacting change: exhibiting and commissioning more work by contemporary artists from historically underrepresented groups; expanding their collections and galleries of historical African, Asian, and Latin American art; and better representing indigenous and immigrant artists in their historical American galleries. Museum educators and interpreters are convening around anti-racist and anti-oppressive practices in the galleries. And, in some cases, museums are returning objects or are better telling the story of their acquisition. However, European collections have been mostly exempted from this work. They are not subject to colonial-era restitution claims, and few people see their galleries as sites for expanding narratives and representation. But if European departments could once excuse themselves as extraneous to efforts toward equity in historically white institutions, that time has come to an end. After the violence in Charlottesville, Charleston, and Pittsburgh, our encyclopedic museums must take steps within their galleries of European Art to combat white supremacist ideology.

What can be done? Our collections are inherited from times that assumed the superiority of European, Christian, male artists, and we now often lack the resources to buy our way towards more diverse collections. If we look to what museum colleagues have done to address histories of racism and colonialism in legacy collections of the Americas, Africa, and Asia, and global contemporary art, we can see that they recommend several avenues for European art to pursue:

- Disrupt the mythos of a singular triumphant civilization encompassing all of Western Europe and extending from Ancient Greece to today. Our grouping of French, British, German, Italian, and Spanish art in suites of “European” galleries, usually the most prominent in the museum, supports a historical fiction present in white nationalists’ claims of racial superiority and in their aggrievement towards globalization: that of a world dominant civilization unified by a shared racial identity. Against the fantasy of commonality within “Fortress Europe,” we must learn how to tell the story of Europe’s historical disharmony and integration in global geographies of empire, trade, and migration. We can look to recent scholarship on historical European identity by our academic colleagues, particularly in medieval studies and critical whiteness studies, as we imagine new ways to talk about and present the geography of our collections. We can do much to change the language in our labels and the works we choose to display on our walls; we must also address the physical architectures of the spaces we have inherited, which tell their own stories.

- Challenge the notion that the cultural life of Europe was uniformly white, heteropatriarchal, and Christian. Jews, Muslims, women, queer people, and people of color pervade the history of European art. After centuries of minimization, we must call attention to their presence. In many cases, our collections already include works that allow us to do so, but they are isolated in Judaica or Islamic galleries, or more often, languishing in storage. A label on a wall can also state what is not there. We should talk about absences. The uniformity of our art history is not the natural order of things, or even historically accurate. There were women artists. American museums did not collect them.

- Speak plainly about the values of the art we exhibit. Celebrate those works that are committed to values we share, and acknowledge those that are not. This does not mean avoiding or minimizing complexity in the artwork we exhibit, but rather learning how to talk about it better, more directly. In my own area of expertise, modern art, there was an outpouring of new work between the two world wars attacking European nationalism, colonial expansion, and restrictive gender roles. Too often we shy away from explicitly stating the political and social values in these works, preferring vague references to their “radicalism” or “avant-gardism.” If a painting targets fascism, this should be made clear in the wall label. If its creation resulted in the artist being targeted and killed by the Nazi party, this should be stated too. And if that same painting, or another, employs misogyny or racist fantasies of Black primitivism, this too must be stated. There can be good reasons to show art with characteristics we now find repugnant, but we need to think hard about what those reasons are and provide our rationale to visitors who may disagree.

- Tell the histories of our collections. In November, Decolonize This Place activists occupied the Egyptian galleries at the Brooklyn Museum with a banner reading, “How was this acquired? By whom? For whom? At whose cost?” Visitors to European art collections have the same questions. Few know why paintings from European royal collections are in their cities. Our silence on this matter promotes the idea of America’s natural inheritance of European culture. Who bought these paintings and brought them to America? Where did the money come from? Who decided these paintings should be permanent features in our cities? What was the rationale for the encyclopedic museum in the first place? If this invites questions about the continued value of displaying European art or of encyclopedic museums in present-day America, those are questions we should welcome and be prepared to answer. Too often, we have outsourced this self-reflection and truth-telling to contemporary artists, often artists of color, who we invite for temporary “interventions” in our galleries without committing to long-term change.

- Finally, and most importantly, we must address the inequities in the staffing and leadership of curatorial departments of European Art. The overwhelming whiteness of staff is a challenge to inclusion efforts across the museum sector, but it is a particular problem in the curatorial ranks and in encyclopedic museums. In the most recent demographic data, 90 of America’s top encyclopedic art museums reported employing an aggregate curatorial staff of 730 people. Of those 730 people, only 11 were Black. 634, or 86%, were white. Art museums’ professional and grant-giving organizations are aware and devoting substantial resources to addressing systemic causes. To my knowledge, there is no effort specifically directed towards diversifying European Art, which is regularly among the least diverse spaces in already majority-white institutions — the least diverse along virtually every axis: socio-economic background, religion, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation. Changing this will require long-term investments and realignments, but there are also candidates who can be hired today, exhibitions that can be greenlit today. Curator Denise Murrell’s landmark exhibition about the representation of black figures in European painting, Posing Modernity: The Black Model from Manet and Matisse to Today is on view right now in a university art gallery, not in one of the major museums that houses European paintings in the United States. France, where it travels next, will show it in the Musée d’Orsay.

Some of these changes are already happening in European art departments, at the Met and at museums across the country. But as a professional body, European art has sat on the sidelines of museum efforts toward diversity, equity, and inclusion for too long. We must energetically join our colleagues who have been doing this work for decades, show them we stand in solidarity and support, and seek out and listen to our critics. They inspire the recommendations here. Museums are not neutral. Displays of European Art are not neutral. White supremacists know it. We must see it too.