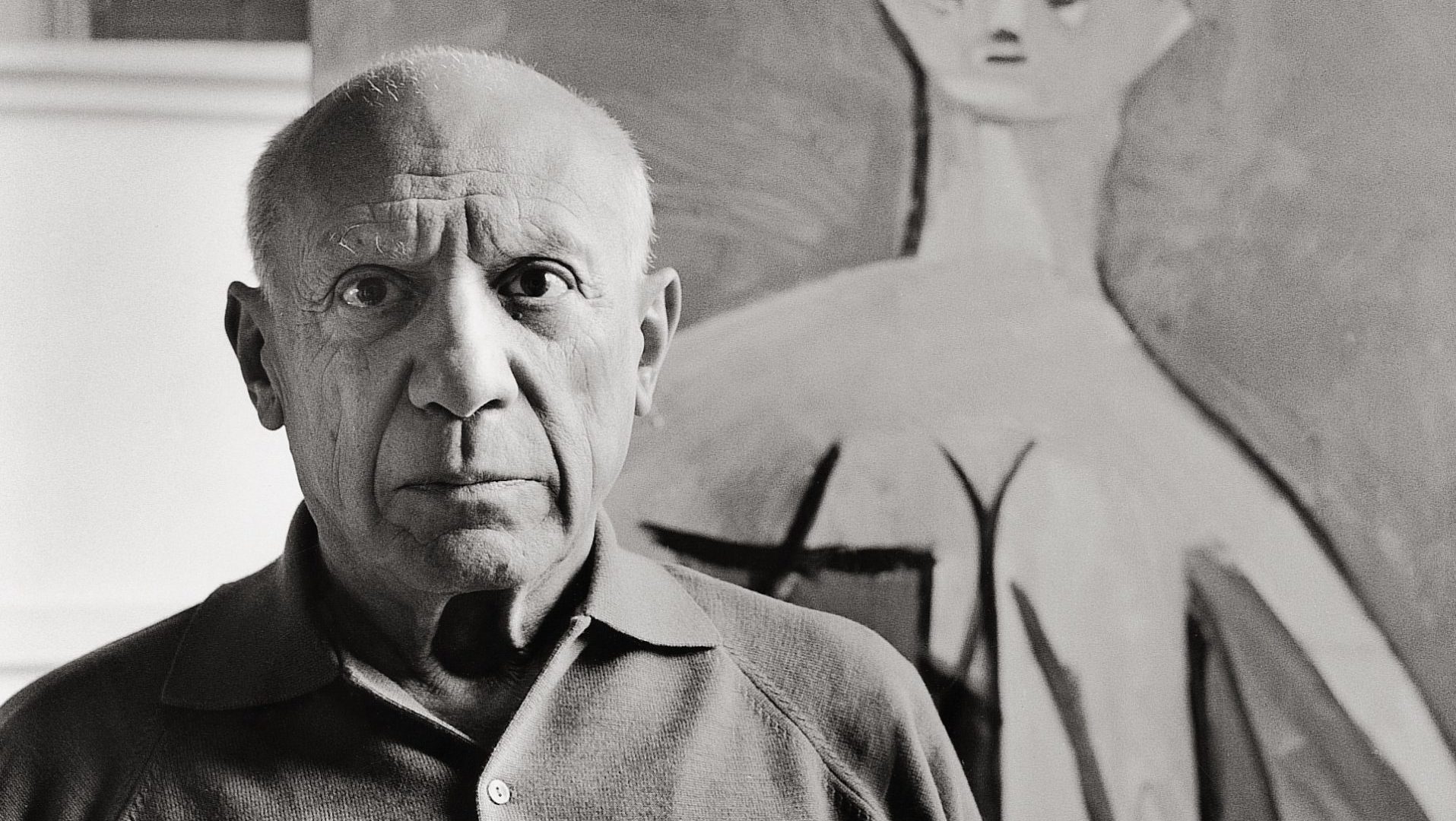

“I am fortunate to have contacts in both governments, and it was just a matter of bringing them together,” he says with modesty. It’s not a trait he inherited from his grandfather, who once told a friend, “I am God”.

The anniversary programme consisted of 40-plus different exhibitions, most in Spain and France, but others in the United States, Germany, Switzerland and beyond, examining different aspects of the artist’s life and work. “The idea was to try and capture the breadth of Picasso’s creativity,” Ruiz-Picasso says, “and also open a dialogue about what he means today, both good and bad. I think, on those terms, it has succeeded.”

We’ll come back to the reference to “good and bad” shortly, as it is crucial in an anniversary year that has featured as many scorching takedowns of Picasso’s character as it has paeans to his genius. But first it is worth dwelling on the way Ruiz-Picasso refers to his grandfather not as grand-père or abuelo but by his surname.

This can be explained by the fact that he was 13 when Picasso died. Since then, his relationship with his grandfather has been professional. As one of five heirs to Picasso’s estate, Ruiz-Picasso instantly became a multi-millionaire when that estate was settled in 1980.

The artist had died intestate, due to a superstition that making a will would hasten his death. Fraught legal negotiations ensued, not just among the heirs but also with the French state, which ended up receiving a plethora of artworks in lieu of inheritance tax and duly opening the Musée Picasso-Paris. The estate was appraised at $250m, though many experts have suggested that the true value was $1bn.

In other words, Ruiz-Picasso didn’t have to work a day in his life. However, from early on he chose a career as a professional promoter of his grandfather’s art. This choice was formalised at the turn of the millennium, when he and his wife launched Fundación Almine y Bernard Ruiz-Picasso para el Arte (FABA), a foundation aimed at exhibiting, researching and preserving Picasso’s work. It also boasts a rich collection of the late master’s pictures, donated by Ruiz-Picasso.

Does he remember his grandad? “Very much,” he says. “I have fond memories of summer holidays at his house in Mougins [the Côte d’Azur village where he spent his final 12 years]. I would travel down from my home in Paris with my father [Paulo, Picasso’s son]. I remember going to bullfights with my grandfather, and also the beach. He was a warm person, very happy to have us around. He used to love watching the wrestling on the television, and I spent many hours sitting in his room with him doing that.”

This is a far cry from the popularly held opinion of Picasso as a selfish, philandering bully. Another of his grandchildren, Marina Picasso – Paulo’s daughter and Bernard’s half-sister – gave an excoriating account of him in her memoir from 2001, Picasso, My Grandfather.

“He drove everyone who got near him to despair and engulfed them,” she wrote. “No one in my family ever managed to escape [his] stranglehold.” This included Paulo, who, according to Marina, was treated with constant disrespect by his father and humiliatingly employed as his gopher. Paulo died in 1975, aged 54, of cirrhosis brought on by alcohol abuse – Bernard was 15 at the time, Marina was 24.

More famously, Picasso showed cruelty to wives and lovers, their happiness deemed less important than their role as the muse for his pictures, and the object of his sexual whims. (When his first wife, Olga, Bernard’s grandmother, was confined to a clinic for months in 1928 with a serious gynaecological issue, he took the opportunity to shack up with his lover, Marie-Thérèse Walter.)

In the wake of #MeToo, some commentators have suggested that Picasso should be cancelled rather than being the recipient of a year-long anniversary celebration. Does Ruiz-Picasso agree?

“I don’t think this is the time to ban or cancel things. Talking is the better option. The number of democracies on earth is decreasing, and those of us lucky enough to live in a democracy can discuss matters to find a solution. This is a privilege.

“Picasso himself lived in an age when freedoms were under threat, and one might see his artworks as a love letter to those freedoms.

“I understand that, most of the time, when people protest, they have genuine concerns and start from a place of good intentions. But they often end up somewhere irrational… like football fans who are happy at their team’s victory but go on to destroy a city after a match.”

Ouch. Ruiz-Picasso commends the Australian comedian, Hannah Gadsby, who made waves in 2018 with her stand-up show for Netflix, Nanette, in which she lambasted Picasso for his attitude to women. Earlier this year, she co-curated an exhibition along similar lines called It’s Pablo-matic at the Brooklyn Museum. It included works by the Spaniard alongside unflattering captions in which Gadsby dubbed him such things as “monumentally misogynistic”.

“The anniversary programme was always meant to examine different aspects of Picasso and his legacy, and that show was a good example,” Ruiz-Picasso says. “Yes, it was critical, but it was in the spirit of engagement. I enjoyed it.”

Another criticism of Picasso Celebration 1973-2023 is that its subject is no longer relevant. In an age when AI (artificial intelligence) and NFTs (Non-fungible tokens) are hot topics of art conversation, how important is an artist 50 years dead?

“I think there is a timelessness to Picasso’s art,” says Ruiz-Picasso. “By which I mean a sense of life and humanity… He had a willingness to share everything about himself on canvas, in a way that few other artists have, and people still respond to that.”

His work certainly remains hugely popular among collectors. Irony alert: according to the latest Burns Halperin Report, a paper tracking equality in the art world, sales of Picasso’s work made more money at auction between 2008 and 2022 than the work of all female artists combined ($6.23bn versus $6.2bn).

Ruiz-Picasso says that in the years immediately after his grandfather and father died, all he wanted to do was grow his hair long, ride his skateboard and play music with friends. He had little interest in school or art. By his early 20s, though, he says he found himself being sucked “slowly and willingly” into the Picasso universe.

He began devouring books, chatting to scholars, and meeting the great dealers of his grandfather’s art such as Ernst Beyeler and Heinz Berggruen. “I came to realise that this was my story, and I needed to take care of it,” he says.

Notable alongside the establishment of FABA was the fulfilment of his grandfather’s wish to have a museum opened in his name in the city of his birth. In 2003, Ruiz-Picasso opened the Museo Picasso Málaga – most of whose exhibits are on long-term loan from FABA.

With the passing of his aunt (Maya Widmaier Picasso) in December and uncle (Claude Picasso) in August, he says the past few months have been difficult. This leaves only one of the artist’s four children now alive: Paloma Picasso, his daughter by fellow painter Françoise Gilot.

It is she who has taken over from Claude as head of the Picasso Administration, which controls the rights to all reproductions and merchandising. Each Picasso heir has a seat at the administration, and they meet once a quarter, often rather fractiously.

In the late 1990s, when Claude agreed to a $20m deal with the carmaker Citroën allowing the artist’s name to be given to a car (the Citroën Xsara Picasso), he was publicly criticised by Marina for deigning “to sell something so banal”.

How are relations among the family now? “No family is easy,” Ruiz-Picasso says with a smirk. “And in our case, things are bigger for being [played out in] public. Nobody gave us a manual on how to handle the gift we inherited from Picasso. We each try to follow the path we think best.”

A few years ago, the Picasso Administration gave approval for an immersive exhibition, Imagine Picasso, which has been touring cities worldwide since 2020. Such exhibitions – featuring a great painter’s work digitally reproduced and projected across a venue’s walls, ceiling and floor – tend to be viewed by critics as pure cashing-in. Ruiz-Picasso hints that he agrees, claiming: “It’s not what I like: selling a digital experience as real art.” However, presumably in a bid not to start a row with the relatives who outvoted him, he won’t say more.

Ruiz-Picasso ends his busy year by taking part in a big Picasso symposium at Unesco’s headquarters in Paris in December. After that, might he take a little break? “Not really,” he says. “The Museo Picasso Málaga gets a rehang of its collection in 2024, and – anniversary year or not – there are always exhibition curators around the world demanding my grandfather’s work, too.”

Even half a century after his death, the sun refuses to set on Picasso’s empire. The questions about his character remain valid, but however they are answered, the work endures.

For details on the rest of Picasso Celebration 1973-2023, visit celebracionpicasso.es