The Captured Runaway, 1856, by William Gale, British, 1823–1909. Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Museum Purchase, Jane H. and Charles E. Parker Jr. Art Acquisition Fund, 2021.48.

On January 25, 2024, the Bowdoin College Museum of Art will open “The Book of Two Hemispheres:” Uncle Tom’s Cabin in the United States and Europe. This exhibition explores the international circulation of imagery that propelled the widespread if controversial fame of Uncle Tom’s Cabin and its author Harriet Beecher Stowe in the decades following its publication in 1852. Stowe’s ardent condemnation of slavery shook an already divided American society and quickly caused a sensation across Europe. Penned here in Brunswick, Maine, The book grappled with several issues of international concern during this period that also resonate powerfully today, including labor exploitation, gender violence, nationalism, colonization, religion, and the very nature of liberty and humanity. In nations like Britain and France, which had previously abolished slavery throughout their colonial empires, the book’s complex themes elicited a mix of responses from excitement to moral outrage and even racist parody. Just months after its appearance in Britain, for instance, one of the country’s leading news outlets The Illustrated London News noted the sweeping impact of Uncle Tom’s Cabin and called it “the book of two hemispheres.”

The Book of Two Hemispheres features examples of painting, sculpture, print, and photography from the BCMA’s collection, along with significant loans from the George J. Mitchell Department of Special Collections & Archives at the Bowdoin College Library and the Harriet Beecher Stowe Center in Hartford, Connecticut. A blend of examples from fine art and visual culture reveals the far-reaching impact of Uncle Tom’s Cabin and the many different ways that its narrative and themes were adapted and reimagined by translators, publishers, illustrators, artists, playwrights, and composers across diverse national and cultural contexts. The book gave rise to many translations and editions, and its most memorable characters and scenes appeared in numerous media. Weak copyright laws meant that Stowe had little control—especially internationally—over changes made to her work. As the story was reinterpreted across decades and continents, it became increasingly detached from its original message, sometimes in explicitly racist ways. Paradoxically, while the book took on a life of its own, Stowe herself became frozen in time as “the author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” her prolific writing career often condensed down to this one literary achievement.

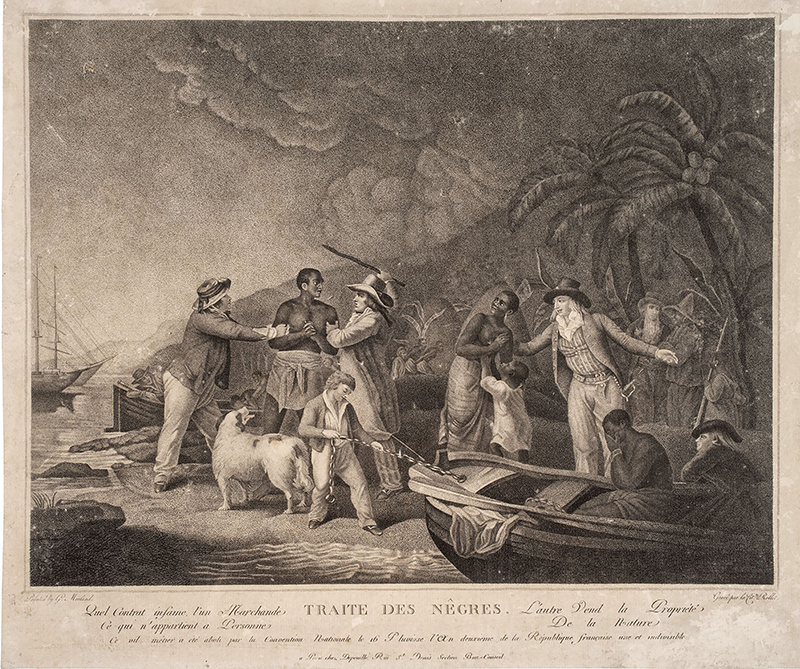

The exhibition is organized roughly chronologically and structured around a timeline with key dates from the book’s publication history, Stowe’s biography, and histories of abolition in the United States and Europe. One of the first objects visitors will encounter is The Slave Trade by French printmaker La Citoyenne (Citizen) Rollet from ca. 1794–1795, which commemorates the abolition of slavery by the First French Republic in the wake of the Revolution of 1789. Rollet crafted this engraving after another engraved reproduction of British artist George Morland’s oil painting The Execrable Human Traffic (1788). The image highlights the cruelty of a father being abducted by enslavers in front of his wife and child, an imagined episode occurring on the coast of West Africa. The separation of families figured into slave narratives and abolitionist literature during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and provides the main plot threads of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Accompanying this print are works by British artists and abolitionists Josiah Wedgwood, Matthew Boulton, and Joseph Collyer the Younger, which call for and/or celebrate the end of Britain’s involvement in the transatlantic slave trade, enacted by Parliament in 1807. While these objects primarily praise white statesmen and white institutions, omitting the protests and revolutions by enslaved people across European colonies in the Caribbean and elsewhere, they still offer important context for the reception of Stowe’s novel in these nations decades later. They also help demonstrate to viewers based in the United States that slavery and abolition were more than just American issues but had global implications.

The exhibition is organized roughly chronologically and structured around a timeline with key dates from the book’s publication history, Stowe’s biography, and histories of abolition in the United States and Europe. One of the first objects visitors will encounter is The Slave Trade by French printmaker La Citoyenne (Citizen) Rollet from ca. 1794–1795, which commemorates the abolition of slavery by the First French Republic in the wake of the Revolution of 1789. Rollet crafted this engraving after another engraved reproduction of British artist George Morland’s oil painting The Execrable Human Traffic (1788). The image highlights the cruelty of a father being abducted by enslavers in front of his wife and child, an imagined episode occurring on the coast of West Africa. The separation of families figured into slave narratives and abolitionist literature during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and provides the main plot threads of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Accompanying this print are works by British artists and abolitionists Josiah Wedgwood, Matthew Boulton, and Joseph Collyer the Younger, which call for and/or celebrate the end of Britain’s involvement in the transatlantic slave trade, enacted by Parliament in 1807. While these objects primarily praise white statesmen and white institutions, omitting the protests and revolutions by enslaved people across European colonies in the Caribbean and elsewhere, they still offer important context for the reception of Stowe’s novel in these nations decades later. They also help demonstrate to viewers based in the United States that slavery and abolition were more than just American issues but had global implications.

Organizing this exhibition has entailed research into the extensive holdings of the Special Collections & Archives at the Bowdoin College Library. During the spring and summer of 2023, Andrew W. Mellon postdoctoral curatorial fellow Sean Kramer, curatorial intern for campus engagement Emily Jacobs ’23, and BCMA co-director Anne Collins Goodyear worked with SC&A staff to access the many examples of visual and material culture related to Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which include an array of objects such as playbills, trading cards, cut-out toys, and songbooks. Given the scope of the collection, it was quickly determined that the exhibition would only be able to focus on one segment of a long and multifaceted history. Uncle Tom’s Cabin continued to be adapted and reimagined throughout the twentieth century, and by midcentury writers such as James Baldwin voiced scathing critiques of the book, with the figure of “Uncle Tom” coming to be invoked mainly as a derogatory term. While this is an important aspect of the book’s reception, the excitement and controversies it caused in the nineteenth century are perhaps less discussed today. Kramer traveled to London over the summer to consult collections and archives at the National Portrait Gallery, Victoria & Albert Museum, and Tate Britain, and to discuss the project with colleagues with expertise in nineteenth-century European art.

Organizing this exhibition has entailed research into the extensive holdings of the Special Collections & Archives at the Bowdoin College Library. During the spring and summer of 2023, Andrew W. Mellon postdoctoral curatorial fellow Sean Kramer, curatorial intern for campus engagement Emily Jacobs ’23, and BCMA co-director Anne Collins Goodyear worked with SC&A staff to access the many examples of visual and material culture related to Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which include an array of objects such as playbills, trading cards, cut-out toys, and songbooks. Given the scope of the collection, it was quickly determined that the exhibition would only be able to focus on one segment of a long and multifaceted history. Uncle Tom’s Cabin continued to be adapted and reimagined throughout the twentieth century, and by midcentury writers such as James Baldwin voiced scathing critiques of the book, with the figure of “Uncle Tom” coming to be invoked mainly as a derogatory term. While this is an important aspect of the book’s reception, the excitement and controversies it caused in the nineteenth century are perhaps less discussed today. Kramer traveled to London over the summer to consult collections and archives at the National Portrait Gallery, Victoria & Albert Museum, and Tate Britain, and to discuss the project with colleagues with expertise in nineteenth-century European art.

Bowdoin College faculty and students were crucial to the exhibition’s conception and development. As the campus community is one of the primary audiences for this exhibition, it was important to seek their guidance and recommendations. Contributions ranged from insightful questions and ideas to practical suggestions for the exhibition’s layout and graphic presence. BCMA staff held group discussions with Bowdoin faculty members from Art History, History, Africana Studies, and English, and with Library staff, and students from a variety of disciplines to discuss strategies to engage with racialized and sometimes overtly racist imagery and language. What came out of those group discussions was the importance of decentering Stowe while still critically analyzing her fraught relationship with the continually morphing history of Uncle Tom’s Cabin and her own public image. There was great sensitivity to the differences in how the book was interpreted by audiences from different cultural backgrounds at different times.

The works on view demonstrate how a story with an antislavery message could nevertheless lend itself to racist interpretations as ideas about enslavement and racial difference were contested and reframed on both sides of the Atlantic. In considering both the novel’s and Stowe’s complicated legacies, viewers may find themselves contemplating equally complicated questions: Did Uncle Tom’s Cabin move society toward justice and liberation, or is it merely a “catalogue of violence,” as Baldwin famously denounced it? How can texts, images, and institutions oppose forms of domination and oppression on the one hand, and still buy into the ideological frameworks that make those forms possible? Although the material featured in the exhibition concludes in 1900, Uncle Tom’s Cabin has never ceased to prompt debate. Its early international reception demonstrates why it still demands our attention today.

Sean Kramer

Andrew W. Mellon Postdoctoral Curatorial Fellow

Bowdoin College Museum of Art

Illlustrations:

The Slave Trade (Traite des Nêgres), ca. 1794–1795, by La Citoyenne Rollet, French. Bowdoin College Museum of Art, The Philip Conway Beam Endowment Fund, 2021.6.

Antislavery Medallion, design introduced in 1787, Josiah Wedgwood, British, 1730–1795. Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Museum Purchase, Laura T. and John H. Halford, Jr. Art Acquisition Fund, 2015.22.