Aaaaaaand we’re back to our regularly scheduled programming. I’m Carolina A. Miranda, art and design columnist for the Los Angeles Times, and I’ve got your first Essential Arts newsletter of the year!

Worlds of wonder

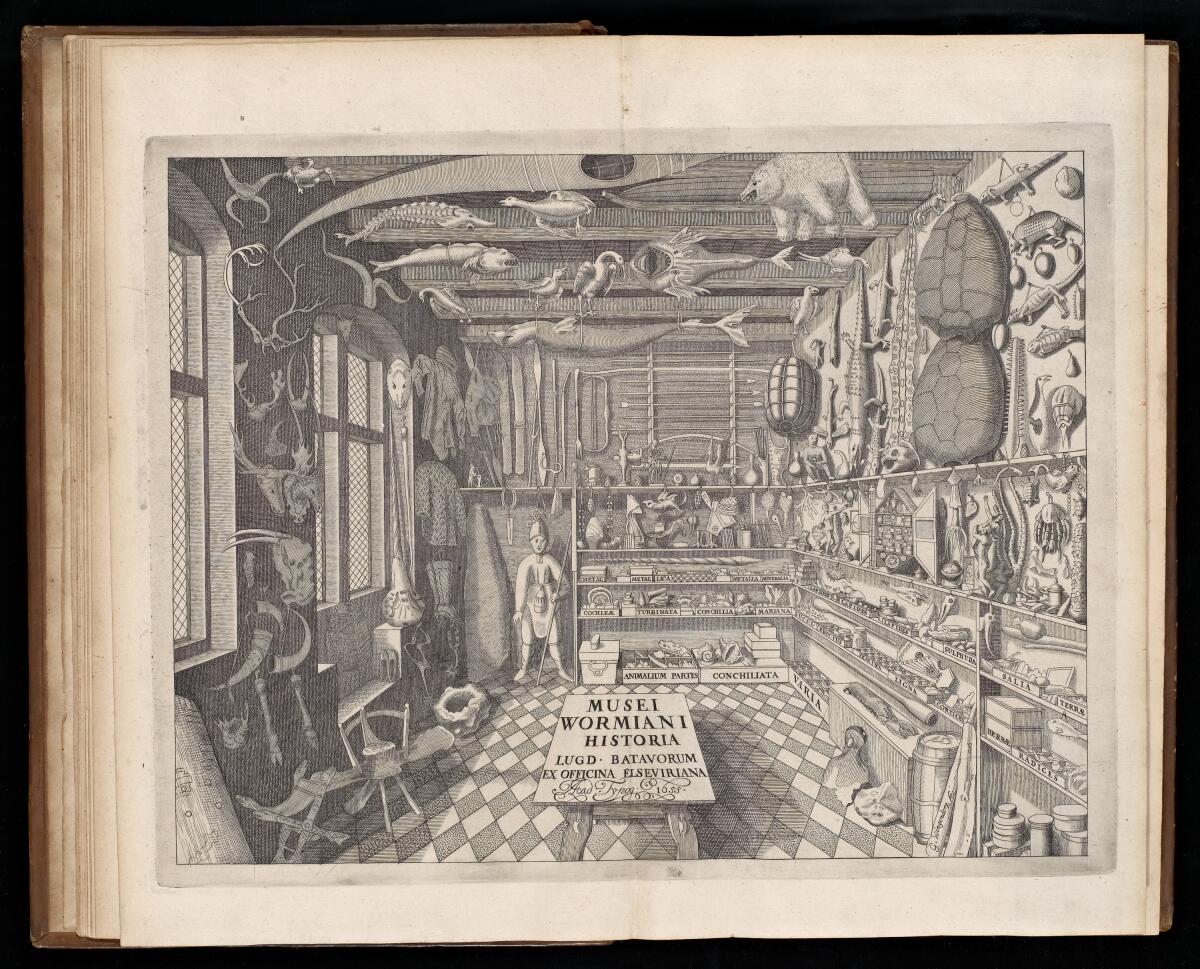

I’m a sucker for a wunderkammer, which literally translates to “room of wonder” — the 16th and 17th century cabinets of curiosities that inspired many modern museums (in particular, natural history museums). These collections could be unfathomably broad, mixing objects without regard to genre. European paintings might commingle with Chinese lacquerwork, anthropological illustrations, the bones of a saint and a taxidermied crocodile suspended from the ceiling.

In other ways, these collections could be very narrow, reflecting the interests or professions of their patrons. (A famous collection held by Elizabeth Bligh consisted largely of seashells gathered by her husband, William Bligh, the sea captain who inspired “Mutiny on the Bounty.”) In all wunderkammer, there are convenient elisions: of the wealth that built them, of the creators behind the objects, of how these items ended up in European hands.

An engraving from 1655 shows the cabinet of curiosities belonging to Danish physician and natural historian Ole Worm.

(Getty Research Institute)

An exhibition at LACMA riffs on the phenomenon, presenting works from the museum’s permanent collection alongside gems, maps, historic engravings and a wild assortment of taxidermy — cue the floating crocodile — drawn from various other collections, including UCLA’s Biomedical Library. Organized by LACMA assistant curator Diva Zumaya, “The World Made Wondrous: The Dutch Collector’s Cabinet and the Politics of Possession” is displayed as the cabinet of an imagined 17th century Dutch merchant. But Zumaya adds a layer by including four contemporary artists whose works explore the erasures and brutalities of colonialism.

The exhibition has transformed a corner of the chilly Resnick Pavilion into a lush sequence of spaces jammed with all manner of objects: decorative chalices, a tapestry of a hunt, classical amphorae, illustrations of 16th century Algerian fashion and a portrait of a prominent Dutch merchant by Rembrandt van Rijn. Taxidermied crabs and macaws share space with a beguiling pocket sundial from the 16th century.

Newsletter

You’re reading Essential Arts.

Carolina A. Miranda guides you through the depth and breadth of Southern California’s complex cultural sphere.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

In an early gallery, Francesco da Castello‘s painted miniature “Salvator Mundi,” from the late 16th century, shows an idealized blond Christ with his hands draped protectively over a globe. (Is there a better metaphor for European colonialism?)

Placed among the older pieces are works by artists such as contemporary conceptual photographer Todd Gray, whose stacked images connect colonized sites with their metropoles. Absorbing (and mordant) is a multimedia work by Sithabile Mlotshwa, which responds to a 17th century Dutch still life by Abraham van Beyeren. The modern piece consists of a collaged riot of gold coins and humbled laborers amid a litter of human skulls — a reminder of the human cost behind so many bewitching wunderkammer.

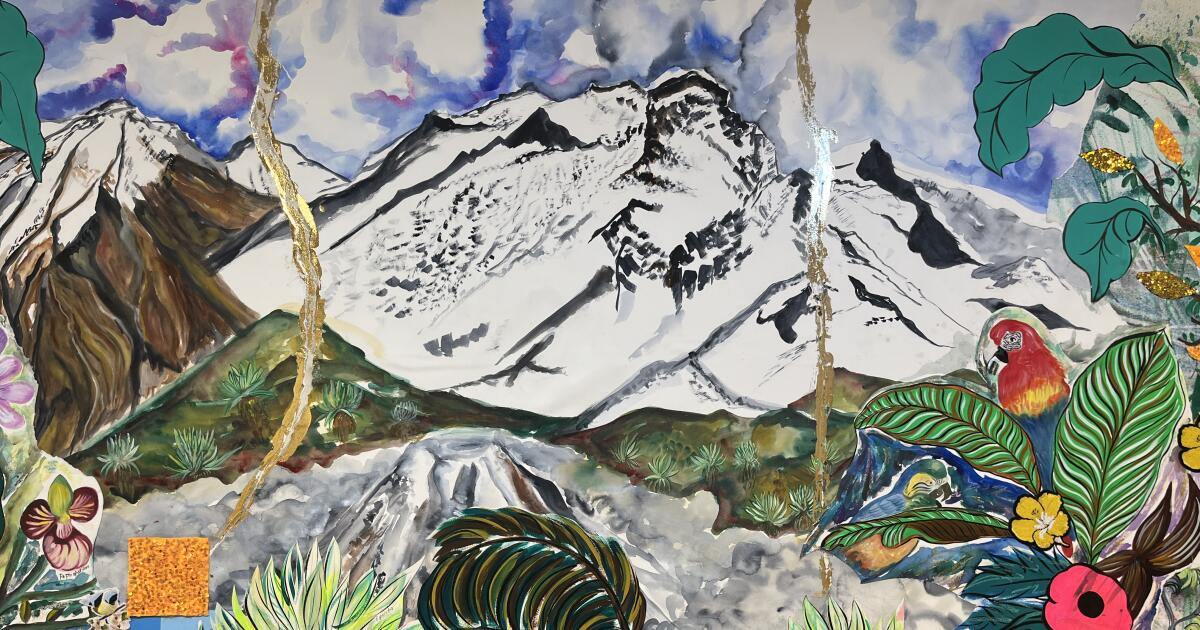

Carolyn Castaño, “Cumanday — Beautiful Mountain (Nevado del Ruiz),” 2023, at Craft Contemporary.

(Josh Schaedel / Craft Contemporary)

The perfect follow-up to “The World Made Wondrous” is a tight little exhibition by painter Carolyn Castaño at Craft Contemporary, right across the street. The Colombian American artist has long been intrigued by traditional paintings of the American landscape. “It’s all very bucolic,” she told me in an interview last year. “It’s paradise. There is no colonialism, no death or destruction.” In the past, she has subverted that gaze by, say, adding a body part to an Edenic landscape.

Her exhibition at Craft Contemporary, “Cumanday — Beautiful Mountain” — which closes on Sunday — features a series of paintings of snowy peaks from Andean tropical glacier chains. These record landscapes threatened by climate change. They also continue her tradition of tweaking 19th century painting: Castaño adds appliqués, sequins and lace in riotous colors, some evocative of Indigenous textiles, others of the plasticky palettes of industrial production.

Most stupendous is the namesake work, “Cumanday — Beautiful Mountain,” referencing the peak otherwise known as Nevado del Ruiz in Colombia. It is grand in scale and ambition, featuring a lush tropical landscape surrounding the jagged peak, all against a toxic pink sky.

It is utterly absorbing. I’d love to see it hanging opposite Frederic Edwin Church‘s romantic 19th century depiction of the Ecuadorean Andes in “Chimborazo,” which resides just across town at the Huntington. That would be a room of wonder.

“Carolyn Castaño: Cumanday — Beautiful Mountain” is on view at Craft Contemporary through Sunday (craftcontemporary.org); “The World Made Wondrous: The Dutch Collector’s Cabinet and the Politics of Possession” is on view at LACMA through March 3 (lacma.org).

Art and design

The Huntington has received four important paintings, including a remarkable portrait of a Spanish marquis by Francisco de Goya. Times art critic Christopher Knight gets into what makes the Goya portrait so special. (It involves a wily minor noble surviving the machinations of the royal court during the Napoleonic Wars.) The other donations are a scroll by Ming dynasty master Qiu Ying, a painting of a tree by David Hockney and a 1940s canvas by Rico Lebrun.

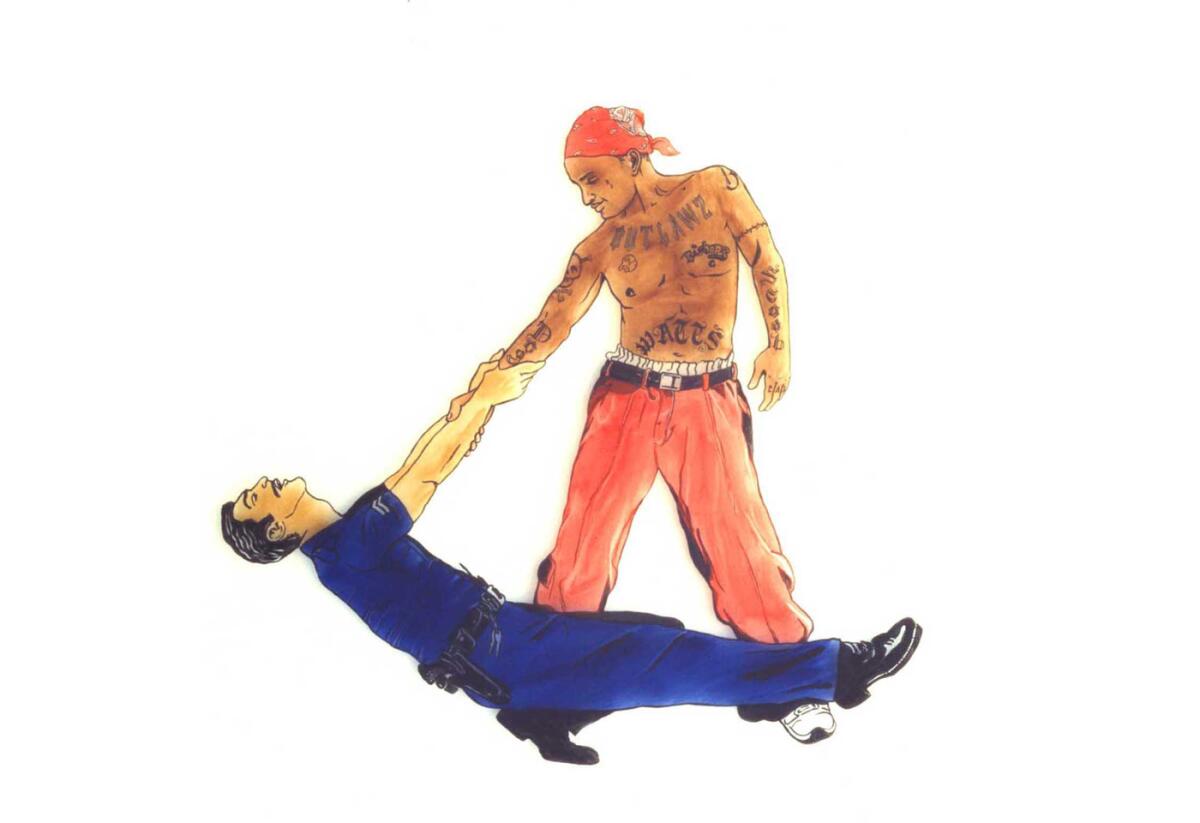

I wrote about a pair of key shows that put the Chicanx body front and center. At the Vincent Price Art Museum, “Teddy Sandoval and the Butch Gardens School of Art” illuminates the work of an underexposed 1970s and ’80s-era artist, while at the Cheech in Riverside, “Xican-a.o.x Body” gathers work by a multigenerational group employing the body in their work. There is history — and bawdiness too.

Alex Donis, “Scoob Dog, and Officer Morales,” 2001, in “Xican-a.o.x. Body” at the Cheech — on view through Sunday.

(Alex Donis / American Federation of the Arts)

And ICYMI, here are some stories from over the holidays:

Knight was disappointed by the exhibition “Woven Histories: Textiles and Modern Abstraction” at LACMA.

I reported on the design of two New York performance venues, the Perelman and Geffen Hall, and how these spaces make audiences feel a part of the action.

LACMA has been cooking up plans to loan chunks of its collection to a not-yet-built Las Vegas museum.

Performing arts

Times classical music critic Mark Swed has thoughts on “Maestro,” the Leonard Bernstein biopic directed by and starring Bradley Cooper. The film minimizes the role that Thomas Cothran played in Bernstein’s life, he notes. But “the glimpses of family life are no doubt accurate.” One thing he wasn’t wild about? The score. “The recorded sound is bombastic,” writes Swed, “instrumental balances, grotesque; the conducting, bland.”

Bradley Cooper as Leonard Bernstein in “Maestro.”

(Jason McDonald / Netflix)

How do actors realistically portray bodily functions onstage — be it coughing, sneezing, crying or reaching an orgasm? Contributor Stuart Miller talks to a range of stage actors to get the deets.

What I’m reading and listening to

Besides jury duty and trekking up to Fresno for a profile (landing soon!), I spent my December immersing myself in two very interesting projects.

Enjoying this newsletter? Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

The first was tech writer Joanne McNeil‘s debut novel, “Wrong Way,” about a gig worker laboring for a tech company called AllOver, run by a CEO who seems to be the love child of Elon Musk at his most Machiavellian and Jack Dorsey at his most annoyingly yogic. (My colleague Matt Pearce wrote about it here.)

One of the topics I’ve long been obsessed with in design is how automation and other forms of technology are resulting in architectural spaces that center our engagement with technology over engagement with other humans. (I wrote about it for the Atlantic in 2018.) This has manifested in other areas too. The Writers Guild of America strike was, in part, about how creative work like screenwriting might turn a field once centered on human endeavor into one in which humans are kept around only to tidy up scripts churned out by machines.

McNeil’s book offers a visceral, bitingly satirical look at what it means when we serve technology at the expense of our own bodies. To give away the premise would spoil it, but I’ll note that in addition to channeling high-minded tech blather in uncanny ways, the novel also features an unforgiving detour through the museum world.

Find the book here.

I also spent December working my way through “In Trust,” a fantastic podcast about the history of Osage landholdings and mineral rights in Oklahoma, hosted by Bloomberg’s Rachel Adams-Heard. The podcast came out in the fall of 2022, but with Martin Scorsese‘s “Killers of the Flower Moon” as an Oscar contender, it is worth revisiting. The series breaks down the systemic issues that resulted in so much dispossession — namely, a legal system that favored white people, with Osages kept in preposterous guardianships.

Interesting to me was the role that allotment — the divvying up of collectively owned tribal lands into individual plots, put in motion by the Dawes Act of 1887 — played in so much displacement. Historian David Treuer has a good explainer on the ravages of allotment on tribal autonomy in his terrific 2019 book, “Heartbeat of Wounded Knee.”

The legacies of allotment have been cropping up in other spaces too. In November, I caught a show at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. organized by painter Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, a citizen of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Nation. “The Land Carries Our Ancestors,” on view through next week, features a wall whose checkerboard installation is inspired by allotment. “The enforcement of this law fragmented Native families and communities, disregarded tribal self-governance, and took land from Native nations,” reads a wall text adjacent to the display. “Yet, Native peoples survive and adapt.”

An installation view of “The Land Carries Our Ancestors: Contemporary Art by Native Americans” at the National Gallery of Art.

(Carolina A. Miranda / Los Angeles Times)

Find “In Trust” podcast at this link. Plus, “The Land Carries Our Ancestors” at the National Gallery is on view through Jan. 15.

Moves

Peter Marks has signed off from his post as chief theater critic for the Washington Post. “You can see that even the New York Times is cutting back on reviews; there’s been a loss of faith in them,” he tells American Theatre. “I think it’s partly due to the lack of imagination in American journalism for figuring out how to convert that print invention into something compelling for digital.”

Passages

Glynis Johns, a Tony Award-winning actor known for her role in “A Little Night Music” and for playing Mrs. Banks in the Disney film version of “Mary Poppins,” has died at 100.

Actor Vinie Burrows, who made her first Broadway appearance in 1950, with Helen Hayes and Ossie Davis, and went on to create a celebrated off-Broadway show called “Walk Together Children,” is dead at 99.

Playwright Mbongeni Ngema, creator of the Tony-nominated musical “Sarafina!,” a work that challenged apartheid in South Africa, has died at 68.

Alexis Smith, a SoCal conceptual artist who combined image and language in works that helped reimagine what art could be, is dead at 74. “If you do your art form well, it is smarter than you are,” she is quoted as saying in an obituary by Times contributor Barbara Isenberg. “I’m stuck in my own time, but the art itself is much more flexible. It can be part of a zeitgeist that I won’t be part of.”

Alexis Smith in 1999.

(Lawrence K. Ho / Los Angeles Times)

Martha Diamond, a painter known for capturing the New York City skyline in bold, expressionistic strokes, has died at 79. (She will be the subject of a presentation at L.A.’s David Kordansky Gallery in the spring.)

In the news

— The takedown of Harvard president Claudine Gay has been disheartening and appalling. Critic Tressie McMillan Cottom has a good essay on the subject in the New York Times: “What has happened at Harvard is not just a blueprint for taking over higher education; it is a strategy for taking over our information environment.”

— As tech writer Taylor Lorenz pointed out on Bluesky, this 2014 essay by Kyle Wagner about Gamergate in Deadspin was prescient about how both-sides-ism and packs of bullies can drive the culture wars: “All culture wars strike these same chords, because all culture wars are at bottom about the same thing: the desperate efforts of the privileged, in an ever-pluralizing America, to cling by their nails to the perquisites of what they’d thought was once their exclusive domain.”

— A survey by the group Heritage for Peace shows that more than 100 ancient and historic sites in Gaza have been damaged by Israeli bombings.

— Isaac Butler at Slate recalls the artistic and political Easter eggs that Mel Chin and the artists of the GALA Committee managed to insert onto the set of “Melrose Place” back in the ’90s.

— Kriston Capps at Bloomberg CityLab has a new weekly newsletter all about design and architecture. It’s called Design Edition and you can sign up right here. In a recent dispatch, he spoke with the American Institute of Architects’ new leader, Kimberly Dowell, the first Black woman to hold the post.

— The dramatic tale of a little-known painting by Kandinsky that was stolen, disappeared, reappeared and was later auctioned.

— Adding Álvaro Enrigue’s “You Dreamed of Empires” to my very long reading list.

And last but not least …

An online museum of Portuguese tinned fish labels and a guide to the best places to find tinned fish in L.A. (Yes, I’m bringing the tinned fish obsession with me into 2024.)