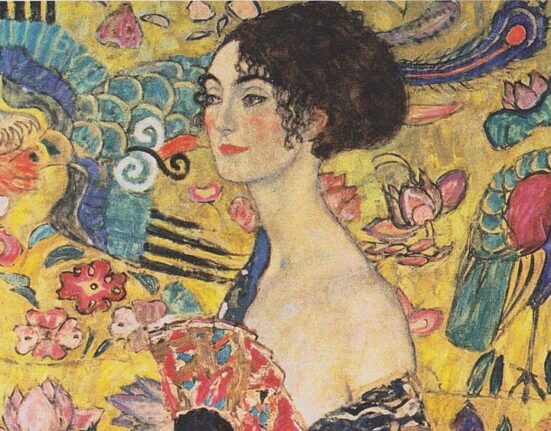

In the fall of 1969, after a night of heavy storms and thunder, a caretaker came rushing out of a baroque church in the old city of Palermo, on the Italian island of Sicily. In tears, the woman had just discovered that a priceless Caravaggio painting that hung over the altar had been cut from its frame and stolen.

More than half a century later, the fate of Caravaggio’s Nativity With St. Francis and St. Lawrence, painted in 1609, remains one of the art world’s greatest unsolved mysteries. Long believed to have been taken by the Italian mafia, the painting, estimated to be worth at least $20 million, is listed by the FBI among the world’s top 10 art crimes.

Now, more than 50 years after the disappearance of the master work, authorities may have their best chance in decades to recover the Caravaggio. And in a dramatic twist, it is coming in the form of a shadowy figure whose own freedom is at stake. A 69-year-old Anglo-Hungarian art dealer named William Veres needs to solve one of the coldest cold cases in art crime history or face jail himself. Veres was arrested at his home in London in 2018, accused by prosecutors in Sicily of running a pan-European smuggling ring made up of tomb raiders, counterfeiters, fences, and frontmen—some of whom are suspected of having connections with the Sicilian mob.

But Veres, an expert on ancient coins known to those in the trade as “The Professor,” says he met with Italy’s anti-mafia police, the Direzione Investigativa Antimafia (DIA), who told him they will put in a good word with prosecutors if he can find the Caravaggio painting. And perhaps, if found guilty, he says he could be spared some 20 years in jail. (The DIA did not return a request for comment.)

“If I managed to recover something, they would speak to the prosecutors,” Veres told me.

Over the past three years, I’ve followed Veres on this unlikely quest, which is the subject of my new podcast, The Professor: The Hunt for the Mafia’s Missing Masterpiece. Together, we traveled all over Europe, meeting with former mafia hit men and turncoats, retired police officers, and shadowy art world figures. As we followed clues to the painting’s whereabouts, we went further than Italy’s police have ever gone.

During his career, Veres has dealt with middlemen linked to the mafia at least once before. The Sicilian mob has long played an important role in the illicit art trade. Now Veres is pulling on those connections to locate the Caravaggio.

“At some stage, somebody within the mafia will be making a decision on whether…to give it back, or how to give it back, under what terms to give it back,” Veres said.

Over the past half century, the Caravaggio painting has become a symbol of the mafia’s enduring power. In 1989, a mafia turncoat admitted to stealing the painting. But since then, Italian police have made scant progress in finding answers. In the podcast, we reveal for the first time how an Italian police investigation into the painting was thwarted in the 1990s. Earlier this year in a park in Naples, I spoke to Ferdinando Musella, the cop who led that probe.

In 1997, Musella’s investigation led him to interview a former mafioso whom witnesses said had tried to sell the painting in the 1970s. Around the same time, this mafioso was a bodyguard for an up-and-coming real estate developer in Milan named Silvio Berlusconi.