A display of low-value coins from Greece helps illustrate how money became part of ordinary peoples’ everyday lives during economic transformation in medieval Europe.

American Numismatic Society / Alan Roche

As trade expanded, banks were established and currency production surged, medieval Europe experienced a major transformation: Suddenly, money was everywhere in daily life. However, although economic development rewarded some, significant disparities remained, sparking new moral quandaries.

A new exhibition at New York’s Morgan Library and Museum—titled “Medieval Money, Merchants and Morality”—traces the ethical and theological debates that sprang from money’s expanding role in medieval European life.

“The interesting thing about money is it hits everything in society,” says Deirdre Jackson, the on-site curator of the exhibition, to the New York Times’ James Barron. She notes that “most people, even the poor,” were caught up in the new monetary economy.

One of the exhibition’s first displays focuses on low-value coins, which made their way into people’s daily lives during this period.

“Previously, mints produced few coins, and these were of high value. This situation couldn’t sustain growth at all levels of the economy,” exhibition curator Diane Wolfthal tells Artnet’s Richard Whiddington. “After the year 1100, more coins, including lower-value coins, began to be produced, which were essential for market penetration into the everyday life of ordinary people.”

Dull and somewhat lackluster in appearance, the coins on view at the Morgan are a sharp contrast to the shiny silver and gold museums typically show.

St. Francis Renouncing His Worldly Goods shows Francis taking off sumptuous garments bought through his family’s textile trading and donning a simple robe instead. Philadelphia Museum of Art

“We’re subverting the idea of treasure, and we’re doing that to make the point that low-value coins were minted in huge numbers,” Jackson tells the Times. While perhaps less visually impressive, these coins helped drive the economy, she says.

Still, even as cash permeated all aspects of life, its presence raised a number of moral concerns within medieval culture, Jackson tells Fast Company’s Talib Visram.

For example, the exhibition features Hieronymus Bosch’s 15th-century painting Death and the Miser, which depicts a man on his deathbed confronting a choice between good and evil: An angel on the right beckons toward salvation; on the left, a demon-like creature holds out an enticing bag of money. The dying miser is caught in a moment of indecision between material gain and spiritual redemption—a reflection of the larger debates about the dangers of avarice and “Christian ideals of poverty and charity,” according to a statement from the Morgan.

A steel strongbox is a symbol of the great wealth some were able to acquire, while others remained in poverty. The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Another artifact reflecting the sharp divides between rich and poor is an elaborate 800-pound steel strongbox that would have been used to store money—a great deal of it—in the home. Elsewhere in the exhibition, a painting from around 1500 depicts Saint Francis, who is shown taking off sumptuous garments bought through his family’s textile trading. In their place, he puts on a simple robe.

“He was questioning the ethics of a society in which there was such disparity in wealth and access to resources,” says Jackson to Fast Company. “For the time, that was really a radical thing to do.”

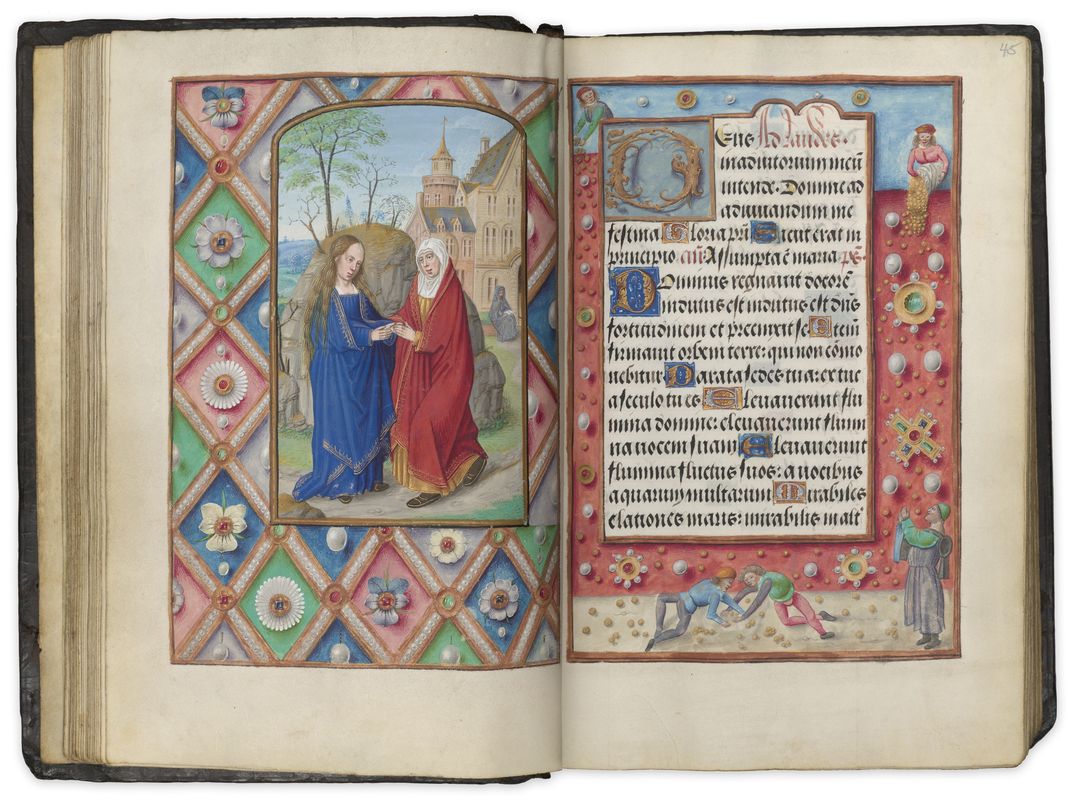

Visitation and Shower of Coins from the Book of Hours illuminated by the Master of Sir George Talbot is one of several medieval manuscripts from the Morgan Library and Museum’s collection on display in the exhibition. The Morgan Library and Museum

These are pertinent questions to consider in this particular space, since J. Pierpont Morgan’s fortune built the mansion the museum occupies. His collection of medieval manuscripts makes up a large portion of the show. “To some, he represented a captain of industry; to others, one of the infamous robber barons,” writes Fast Company. “As in the Middle Ages, the Gilded Age presented fundamental questions about the fairness of capitalism.”

These overlapping histories are a reminder of how the exhibition’s subject remains relevant today.

“I hope visitors will see how complex medieval discussions of money were and think about the role money plays in their own lives,” Wolfhal tells Artnet. “We have much to learn from the medieval past.”

“Medieval Money, Merchants and Morality” is on view at the Morgan Library and Museum in New York through March 10, 2024.

Recommended Videos