The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s European Paintings galleries, which reopened last November after a thoughtful, beautiful refurbishment and reinstallation, now display more than seven hundred works, including a discrete selection of sculpture and the decorative arts (and even a small sampling of nineteenth-, twentieth-, and twenty-first-century paintings). After efforts to raise $600 million to fund David Chipperfield’s design for the wing housing modern and contemporary art stalled in 2016, those plans were shelved, and the museum shifted its attention to the long-deferred maintenance of the second-floor galleries’ skylights. This complex undertaking was launched in 2018 after approval from New York City’s Landmarks Preservation Commission. Housed in attics above the glass-paneled ceilings, the corrugated wire-and-glass skylights consisted of a louver system dating from 1939 that had last been remodeled in 1952. In replacing some 1,400 skylights covering 30,000 square feet at a cost of $150 million, the primary objective was to improve the way that natural light, in combination with artificial lighting, enters the suite of forty-five galleries at the top of the grand stairway that has occupied pride of place at the Met since the building was completed in 1880.

The five-and-a-half-year project, initiated under the direction of Keith Christiansen, former John Pope-Hennessy Chairman of the Department of European Paintings—in whose honor several outstanding recent acquisitions, such as Nicolas Poussin’s The Agony in the Garden (1626–1627) and Charles Le Brun’s The Jabach Family (circa 1660), have been made—and brought to completion by his successor, Stephan Wolohojian, also provided the opportunity to construct new heating and air-conditioning systems, with impressive improvements in sustainability and energy consumption. While nearly all the galleries had to be de-installed and the paintings relocated or placed in storage, Giovanni Battista Tiepolo’s monumental decorations for the grand reception room of the Palazzo Dolfin in Venice, three of which have greeted visitors to these galleries since the late 1970s, remained in place throughout the work. “It’s open-heart surgery,” quipped the Met’s director and CEO, Max Hollein, “and the patient is awake.”

This was the first of four major capital projects. Of the three still underway, by far the most ambitious is the 135,000-square-foot Tang Wing for modern and contemporary art, designed by the Mexican architect Frida Escobedo. Launched in November 2021 by a gift of $125 million from the philanthropists Oscar L. Tang and Agnes Hsu-Tang—the largest capital donation in the museum’s history—it is estimated to cost $500 million and is slated for completion in 2029. (At the beginning of May, the Met announced that it had secured $550 million in private donations for the new wing.)

Beyond the lighting, the European Paintings galleries project is less a physical reconfiguration of the spaces—while some doorways have been widened, the layout, established in 2013, remains essentially the same—than a thorough reconsideration of the display of the Met’s collection of paintings from Giotto to Jacques Louis David. Chronology dominates the new sequence, and, particularly in the Renaissance galleries, artists from Northern Europe are brought into conversation with their Italian counterparts. You can choose to follow the numbering that is rather tentatively inscribed on the doorjambs at each gallery, but there is flexibility to the sequence. The curators have devoted entire rooms to El Greco, Rembrandt, and Goya; the museum’s five Vermeers are beautifully displayed on one wall in gallery 614; its paintings by Velázquez, Poussin, and David have never been so well installed. The same can be said of the superb sixteenth-century Venetian paintings in gallery 608; the Holbeins brought together with masterpieces of Italian portraiture by Andrea del Sarto, Bronzino, Salviati, and Sofonisba Anguissola (the spectacular full-length Portrait of a Noblewoman on loan from the Kletsch Collection) in gallery 612; and the near-perfect symmetrical hang of large-scale paintings and portraits by Rubens and Van Dyck in gallery 618.

The chronological progression is punctuated by occasional thematic displays. There are rooms devoted to still lifes, the artist in his or her studio, oil sketches, and the different supports on which painters have worked (primarily wood and copper). There are also occasional atemporal confrontations that function at their best, the critic Karen Wilkin has noted, “rather like seasoning, a squeeze of lemon, that sharpens our perceptions.”1

When you enter the first long gallery devoted to fourteenth-century Florentine and Sienese religious painting by the right-hand set of doors, you might wonder if you have come to the right place. For you are immediately confronted by Max Beckmann’s postwar triptych The Beginning (1946–1949), flanking Jean Bellegambe’s The Cellier Altarpiece (1511–1512): two tripartite masterpieces in dialogue. On an adjacent wall Francis Bacon’s Three Studies for Self-Portrait (1979) is placed next to a fourteenth-century Florentine Head of Christ attributed to Niccolò di Tommaso. In other galleries paintings by artists such as William Orpen, Henri Matisse, Chaïm Soutine, Salvador Dalí, Elaine de Kooning, and Kerry James Marshall create intentionally disruptive juxtapositions. These are neither disturbing nor jarring—they are exhilarating.

Hanging paintings by Cezanne and Picasso in the El Greco gallery can be justified historically—Picasso studied El Greco’s works from the time he was a teenager—but they serve an aesthetic rather than a didactic purpose by enhancing an already dazzling display. Before visiting the galleries, I was skeptical about the pairing of Duccio’s transcendental Madonna and Child (the Stoclet Madonna, circa 1290–1300), acquired in 2004 for a record—and much-reported—sum of over $45 million, with Ingres’s The Virgin Adoring the Host (1852), which entered the museum as a gift the following year. Placed at the center of the gallery that brings together for the most part fourteenth- and fifteenth- century paintings and objects used for private devotions (under the rubric “Beyond the Wall”), the Duccio presides in a far more dignified space than it previously occupied. Now as before you can see the singe marks made by candle flames on the lower edge of the panel. Ingres’s exquisite work acts as a deferential partner to Duccio’s monumentally tender depiction, while demonstrating the continuing function of such small-scale paintings to nourish personal piety over the centuries.

The Met’s curators and designers have shown impressive restraint in their selection, as well as thoughtfulness about the museum’s various audiences for older European art. With one notable exception, the galleries are hung spaciously and are not overcrowded with artworks. Most rooms have at least one painting, if not more, designated a Collection Highlight, with a longer label. There is a preference for forthright, saturated tones as backgrounds on the walls—nine hundred gallons of paint were required—and a palette of five colors has been used. For the walls of the early Italian galleries the designers have found an elegant “gull-wing gray.” Also effective are the vibrant blue of the introductory Tiepolo gallery, curiously called “gentleman’s gray”; the deep purple-brown (“galaxy”) used for the sixteenth-century Venetian and El Greco rooms; and the earthen red (“red rock”) for the Italian Baroque and Goya galleries. Less felicitous is the choice of a baby blue (“province blue”) for the ten eighteenth-century galleries with which the installation concludes. It has a somewhat deadening effect on these French and Italian paintings.

During the past decade and under the leadership of Michael Gallagher, the recently retired Sherman Fairchild Chairman of the Department of Paintings Conservation, conservators have cleaned and restored an impressive array of paintings in anticipation of the reinstallation. Masterpieces by Giotto, the anonymous fourteenth-century Bohemian Painter, Giovanni di Paolo, Fra Angelico, Filippino Lippi, Jacopo Bassano, Moretto da Brescia, Poussin, Charles Le Brun, and David—to name but a handful—have been examined and treated.

Most spectacularly, Rembrandt’s Aristotle with a Bust of Homer (1653) was meticulously restored by Dorothy Mahon, who removed the haze-like bloom that had clouded the surface of the canvas since its last cleaning in 1980. The rich black velvet of Aristotle’s tunic is revealed in unimagined depth and texture. The philosopher’s chain of office sparkles in the penumbral light, as does the profile medallion of Alexander the Great hanging from it, below the voluminous drapery of Aristotle’s lemony-gold satin mantle, rendered in dabs and dashes of impasto. Even the glinting gold band on the little finger of Aristotle’s left hand is now visible.

It should also be noted that with very few exceptions, the paintings are not displayed behind glass. This is normal procedure in permanent collection galleries, but courageous and commendable today when vandalism by climate activists has compelled many institutions to reconsider the vulnerability of unglazed works (and their frames). There are lines of tape on the floor demarcating the appropriate distance from the walls at which viewers should stand, and on all of my recent visits the guards were vigilant and courteous in enforcing this (and the visitors unfailingly compliant).

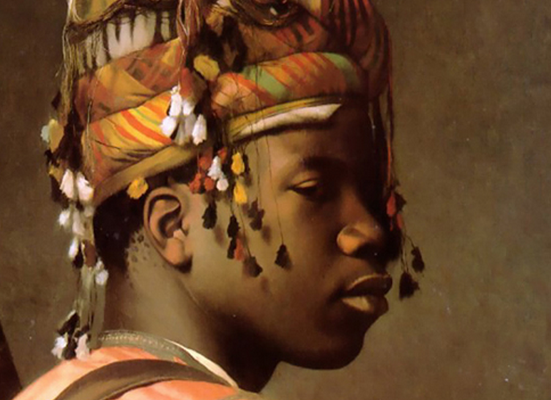

The labels and text panels in each gallery are for the most part succinct, accessible, and informative. In Tiepolo’s The Triumph of Marius (1729), which dominates the large entrance hall, the sympathetic depiction of the vanquished North African king Jugurtha—standing upright and alone in his red cloak, more prominent than the victorious Roman general in the chariot behind him—serves as a palimpsest of sorts. An effort has been made to avoid the triumphalism frequently implicit in surveys of European art. Europe, we are told, was as much a geographical construct as a coherent entity, and the legacy of Mediterranean antiquity influenced many cultures beyond the continent. Hence the inclusion of a superb fourth- or fifth-century bodhisattva from Gandhara (present-day Pakistan), as well as a radiant eighteenth-century Mexican lacquered wood bowl illustrating an episode from Virgil’s Aeneid. If you look closely at The Triumph of Marius, you see the portrait of the thirty-three-year-old artist halfway up the left-hand edge of the canvas: his is the only face to engage the viewer directly. But it stretches the evidence—and is also anachronistic—to claim, as the general introductory panel does, that “many painters similarly worked to define Europe, as well as its constituent parts, often by staging encounters between the self and the other.”

While likely beyond most visitors’ recollections, until 1980 the Met’s European galleries presented a far broader survey of paintings, from Giotto to Picasso, with Raphael’s Colonna Altarpiece (circa 1504; see illustration) at the top of the monumental stairway. Only in that year were the nineteenth-century paintings moved to the thirteen newly built André Meyer galleries, whose modernist design was heralded by the architectural historian Ada Louise Huxtable as “a near-perfect synthesis of the arts of scholarship, building and display.”2 In anticipation of the gift of the Impressionist and Post-Impressionist collection of Walter and Leonore Annenberg, in 1993 this wing was transformed into a Beaux-Arts suite of twenty-one galleries, and in 2007 by the addition of nine new rooms.

The bequest to the Met of the Annenberg collection in 2002, with the provision that the works be shown together in contiguous galleries and not be lent—mercifully without any stipulation that the installation replicate the midcentury modern interiors of the Annenbergs’ California residence at Sunnylands—reminds us that the growth and preeminence of the museum since its incorporation in April 1870 have depended largely on the acquisition of collections en bloc from trustees and donors, most of whom have sought to attach conditions on presentation and display. (Among the Met’s greatest benefactors, John Pierpont Morgan and Louisine Havemeyer were unusual in imposing no such restrictions to their gifts.) After a decade spent in temporary quarters—Allen Dodworth’s Dancing Academy at 681 Fifth Avenue and James Renwick’s Douglas Mansion at 128 West 14th Street (which Henry James remembered as “stately though scrappy”)—in March 1880 the Met finally took possession of the High Victorian Gothic structure in Central Park designed by Calvert Vaux and Jacob Wrey Mould. By 1895 the growth and ambition of the museum led to its reorientation away from the park to Fifth Avenue, with a monumental Beaux-Arts façade, entrance hall, and grand stairway designed by Richard Morris Hunt, completed by his sons, and inaugurated in December 1902. These are largely unchanged and are familiar to all who visit the Met today.

Of the founding purchase in March 1871 of 174 old master European paintings, mainly of the Northern schools, eleven works remain on display in the new installation, including paintings by Salomon van Ruysdael, Poussin, Van Dyck, and Jean-Baptiste Oudry. An even greater number—some fourteen gifts and thirteen works acquired through his funding—come from the collection of the Met’s greatest early donor, the banker and railroad financier Henry Gurdon Marquand. This was a gift of “rare munificence,” as James noted, that included Vermeer’s Young Woman with a Water Pitcher (circa 1662), even if Marquand’s “Leonardo”—Girl with Cherries (circa 1491–1495)—has long been reattributed to Marco d’Oggiono, and his “Lucas van Leyden” of Joseph Interpreting the Dreams of Pharaoh (circa 1534–1547) to Jörg Breu the Younger. The earliest (and most momentous) endowment for acquisitions, a gift of $6 million from the estate of Jacob S. Rogers—the miserly and misanthropic president of Rogers Locomotive and Machine Works in Paterson, New Jersey—known as the Rogers Fund, has supported the acquisition of no fewer than eighty of the paintings currently on view.

As Calvin Tomkins made clear in his still-indispensable Merchants and Masterpieces: The Story of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, published in 1970 in celebration of the institution’s centenary, successive presidents and trustees have walked the delicate line of soliciting entire collections of European art while trying to discourage donors from determining the placement of their bequests or imposing restrictions upon them. As noted by the Met’s first president, John Taylor Johnston, a lawyer, railroad tycoon, and discriminating collector of American paintings, “We must curb the exuberance of our donors except in the article of money, of which they may give as much as they please.” His son-in-law Robert Weeks DeForest, who succeeded J.P. Morgan as president of the Met in 1913, lamented that the museum “cannot wisely prevent the proper arrangement of its growing collections as an integral whole by accepting gifts conditioned on perpetual segregation.”

Yet for much of the twentieth century the development of the Met’s collection of European art was dependent precisely on agreeing to such terms. Outstanding collections from the bequests of the department store magnate Benjamin Altman (1913); his successor at B. Altman and Company, Colonel Michael Friedsam (1931); the Met’s seventh president, the banker George Blumenthal (1941); and the banker Jules Semon Bache (1944) were accepted in accordance with the donors’ desire that the collections be kept together and shown in contiguous galleries.

The most extreme example was the acceptance in 1969 of the collection of Robert Lehman, the investment banker and first chairman of the museum’s board—a position created to secure the donation—which is housed in galleries that replicate the rooms in his homes at 7 West 54th Street and 625 Park Avenue and is installed, as Tomkins put it, “forever inviolate from other objects.” The glass-domed wing on the Met’s west façade overlooking Central Park, built to accommodate the Lehman collection, was inaugurated in May 1975.3 The final manifestation of this insistence on replicating the collectors’ interiors is the seven first-floor galleries devoted to Jack and Belle Linsky’s collection, which opened in 1982. The Linsky fortune was made from the Swingline Corporation, manufacturer of staplers and office stationery. Forty years later the galleries remain mostly overlooked and little visited.

While some donor restrictions still apply—works from the Altman, Annenberg, and Wrightsman collections may not be lent to other institutions, and the Lehman wing continues as a separate entity—the reinstalled European galleries represent the Met’s most ambitious attempt to integrate masterpieces from all the donations and bequests, including a handful of impressive loans and promised gifts such as Antoine Le Nain’s A Peasant Family (circa 1640–1648), an exquisite small painting on copper, and Orazio Gentileschi’s Madonna and Child (circa 1607), the latter from the recently announced benefaction of the television producer Dick Wolf of Law and Order fame. While the absence of the fourteenth-century Sienese painter Simone Martini in the new hang is somewhat surprising—especially since three of his panels can be seen in the Lehman galleries—the presence of the Lehman collection’s magnificent El Greco Saint Jerome as Scholar (circa 1610) in gallery 619 adds immeasurably to the impact of that room. Similarly, I was struck by the grandeur of Luis Meléndez’s The Afternoon Meal (La Merienda) (circa 1772) from the Linsky collection, the Met’s only work by this Spanish still-life painter, which more than holds its own in the Goya gallery. It is also remarkable that an impressive gallery devoted to the arts of the Spanish Americas (626)—primarily eighteenth-century religious paintings and objects from Mexico City—has been assembled entirely through gifts and acquisitions made over the past decade.

The Met’s vice-president of capital projects, Jhaelen Hernandez-Eli, has described the skylight renovation as part of a progressive mission that renews faith with the founding principles of the institution:

What, then, are our galleries if not prisms that shift our gaze and reverence toward the act of making? Our collections are a testament to labor and provide the inspiration needed to see the people who construct our galleries and improve our infrastructure as artisans, whose work will one day be the subject of study by the art historians of the future…. The galleries themselves provide an opportunity to mine contemporary acts of making to deepen our understanding of our collections while engaging with climate change and socioeconomic inequity in quantifiable ways.4

A courageous if controversial statement—Hernandez-Eli is also on record as noting that “who makes those walls is as important as who you put on those walls”—but one that in some ways channels the priorities of the Met’s founders. The museum “should serve not only for the instruction and entertainment of the people,” intoned the lawyer and diplomat Joseph Hodges Choate at the museum’s dedication in March 1880, “but should also show to the students and artisans of every branch of industry…what the past has accomplished for them to imitate and excel.”

There are many reasons for visiting the new galleries: the lighting is radiant, the displays are generous and informative, and the emphasis on quality, beauty, and art history is commendable. (The museum also hopes that the reinstallation will encourage visitors to look “more deeply into histories of class, gender, race, and religion.”) Tomkins worried in 1970 that the popularity and success of civic juggernauts like the Met might diminish, if not destroy, the intimacy of close looking and aesthetic engagement that art museums offer:

What kind of privacy is possible on Sunday afternoons at the Metropolitan, when the concentration of sixty or seventy or eighty thousand people in the galleries make it nearly impossible to view the works of art?

While crowding and access are legitimate concerns, particularly for temporary exhibitions, the European Paintings galleries were not excessively trafficked on any of my recent visits. However, such is the depth, range, and interest of the newly shown collection that to try to cover the entire wing in one go is a challenge to the eyes, mind, and feet. Repeat visits are recommended.

Happily, the Met’s audience is famously resilient, as the playwright Alan Bennett noted after an afternoon spent at the exhibition “Tapestry in the Baroque: Threads of Splendor” in October 2007. “The museum is teeming with visitors, a terminus of art,” he confided to his diary, “and what strikes one…is the stamina of older women, the worn-out men trailing in the wake of their wives still eager, still determined on self-improvement, still keen to know.”5