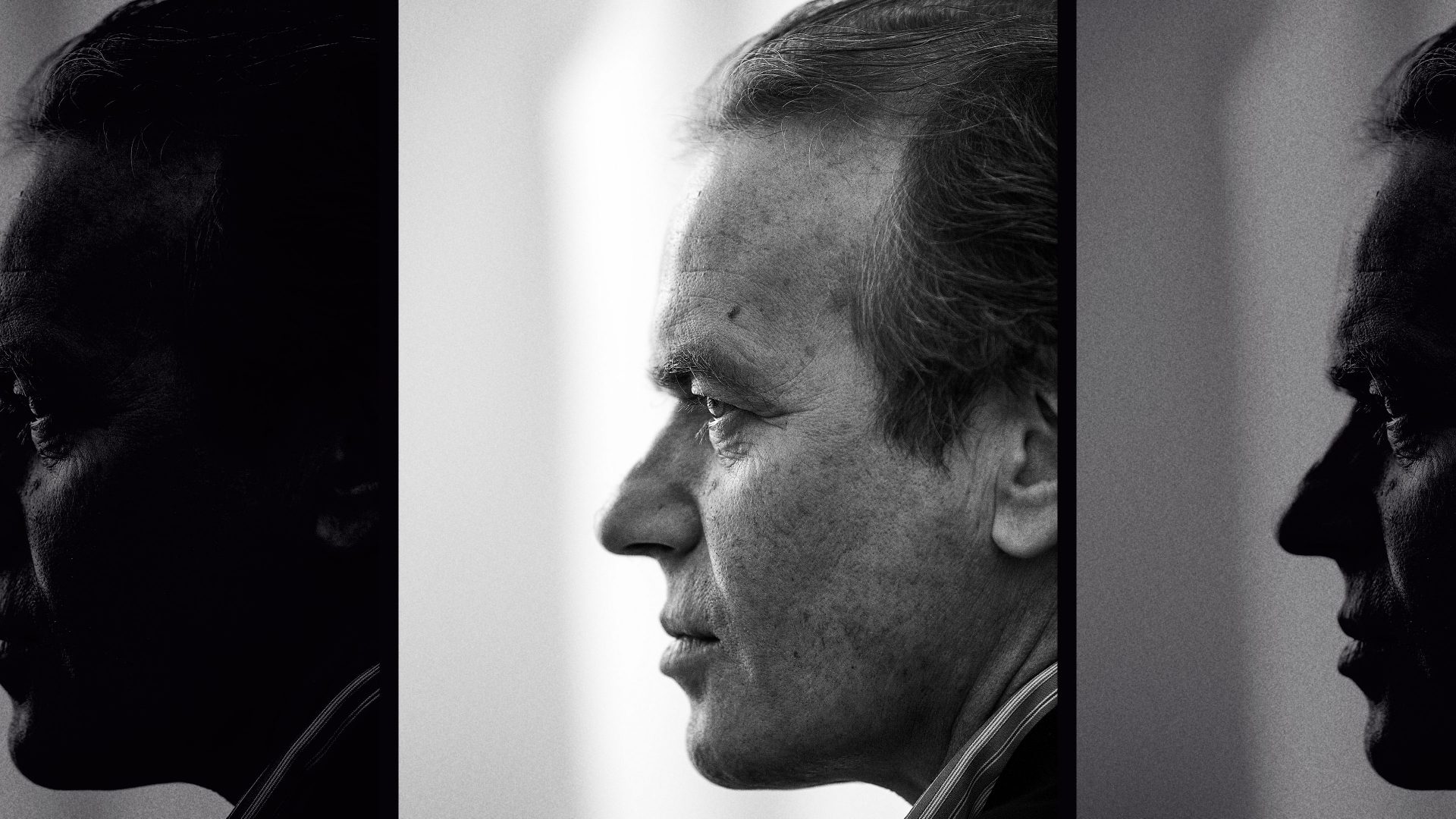

It was all in Martin Amis’s tone, I think – which makes sense for a writer of voice. His listeners would be in a state of anticipation, awaiting that familiar aspiration: a catch in the intake of breath such that emphasis fell – like a finger dallying towards an erogenous zone – exactly where you both hoped and feared it would. Over-egged it became a semi-sneer – under-cooked it collapsed down like souffle that hasn’t so much failed, as given up by reason of ennui.

A couple of instances I remember: Martin had just spent a week shadowing Tony Blair, who was still prime minister at this time. He’d been telling me how when you were aboard a vehicle with the serving PM, the traffic parted ahead of you and your entourage like so much metallic surf, making it all too easy to understand the delusions of adequacy that affect those in power. “But what about Blair, Martin?” I asked, “what’s he really like?”

“We-ell,’ Martin went into drawl-mode, a sure-fire indication that a bon mot was coming. “I’ll tell you one thing, he’s not a reader.”

The ambiguity here was definitely intentional – Martin both meant to send himself up for daring to’ve imagined that Blair might have read his own stuff, and to say unequivocally that the wannabe great statesman wasn’t a reader of anything much at all.

Here’s another: Martin was going off to play tennis with a journalist from the Observer who we both knew, and who happened to be called Tim. The game being a pretext for an interview, or perhaps vice versa. I saw him shortly after and asked him how it had gone. He pondered this for a moment “We-ell…” before delivering a devastating verdict: “what can I say, he’s a Tim.”

(An alternative emphasis here might be: ‘he’s a Tim.’ But you can see that either way, this is an extension into everyday life of his fictive preoccupation with nominative determinism, all the way from Charles Highway, via John Self, to Keith Talent and Nicola Six.)

A third, perhaps more controversial example of Martin’s wit was his reply on being asked whether he’d ever considered writing a children’s book – and I believe I was present for the first extempore instance of this, he later repeated it during a broadcast interview – “I might… if I had brain-damage.”

That was in a pub, in Manchester around a decade ago, when Martin was professor of creative writing at Manchester University. I’d gone up to do an event with him – on writing about sex as I recall – and late that evening, after the dinner that had followed, he walked me back to my hotel. I think it was the only time I’d ever seen him properly angry, provoked not by politics or personality of any kind, purely by grammar.

“Did you hear that idiot, X,” he said, referring to one of his colleagues who’d done the introductions for the event. “Did you hear him say ‘some of the books which he has written’?”

I grunted assent – but of course, I hadn’t.

“Which!” Martin near-screeched, “Which! When it should’ve been ‘that’, and this man calls himself a teacher of writing!”

If this makes him seem punctilious, trust me: he wasn’t – he simply believed in writing not as some sort of therapy by other means, or as a mere method of conveying this or that story; but as a craft that might, by reason of its practitioners’ genius, be raised to the level of art. When he entitled a collection of his shorter-form writing The War Against Cliché, he was positioning himself right in the front line of a battle against the banality of populism, whether of the left or the right.

(And as an aside, when one of my colleagues at the university sent an email to the students offering them a selection of “cutting-edge” modules, taught by “world-beating” academics’, and I responded by sending him an email saying it was good to see him “still waging the war against cliché”, the colleague complained about me to our boss.)

It was the caring about writing that made Martin such a cynosure – not the extraneous aspects of his life that were so relentlessly reported on. Throughout the period in which he lived and wrote, all fame became a matter of mere notoriety – but he hailed from an era in which, for all its failings, talent created its own monoculture, and people were famous for what they did. I remember one little flurry of Martin-baiting that wasn’t about his teeth, or his divorce, or the size of his advances, or his daughter who was conceived – gasp! – outside of wedlock, but was rather sparked by Anna Ford, the erstwhile autocue reader, telling (or perhaps selling to) the Mail on Sunday the cosmic tittle-tattle that she considered Martin to’ve been a bad godfather to her children.

Really, this was the contemporary world of Twittery hysteria shivering into being – and Martin, as a writer whose private life had unfortunately become of interest to those who never read books without pictures, he necessarily attracted a lot of abuse. I never saw him anything more than wearied by this – he was too wise to imagine it would go away (until, of course, he did), and absolutely accepted that it was the work that was the priority, while there was no way its reception could be anticipated, let alone manipulated.

A lot has been written already about the balance between the fiction, the criticism and the journalism. I am inclined to the view that his highly poeticised prose was above all preeminent: its great rolling out throughout his career, as it were some lexical carpet that might be cut to fit a feuilleton as much as a roman fleuve. For writers of my generation, he opened up a channel in English prose writing between the burgeoning slang of the 1970s, and the still-antiquated literary language of the time – and this was a wholly reciprocal interaction, such that literary novels became gamier (in the grouse sense), while the language of the street acquired a certain high-table lustre.

Janus-faced, Martin introduced the intelligentsia to Space Invaders, and the pub quizzers to… well, to Martin Amis, who was so invested by the poetry of prose both created and contemplated in isolation and tranquillity, that he once told me he thought it a sort of cosmic solecism that Shakespeare had been a dramatist. As for the oft-made accusation of misogyny – a crime that shows up, inevitably, as a stain on the page – in person I never heard or saw him say or do anything whatsoever that objectified or otherwise denigrated women.

He once admitted to me that he felt completely in thrall to women – which is the state all men who love women should rightly attain to. Martin had a way of sharing what he felt the best gags were in any forthcoming work in advance – as if they were little amuse bouches. One I recall from The Information was this evocation of sex between the impotent priestly protagonist of George Eliot’s Middlemarch and his frigid wife: “as for Casaubon and Dorothea, sex between them would like trying to fit an oyster into a parking meter…”

An arresting image, and one that flouts prudish contemporary sensibilities – yet what’s its real purpose, surely only the necessary revelation of all serious literature since Freud: the inextricable intertwining of sex and death. No, Martin’s masculinity always seemed a matter of boyishness more than braggadocio to me – the sports enthusiasms, from darts to tennis to football. And the liking for pub culture that went with these pursuits.

In political matters, Martin could, I think, be a little naïve. It was a matter of record that he fell out with his great friend Christopher Hitchens over the agon of Amis’s book about Stalin, Koba the Dread. That agon being Hitchens himself, and any old ‘tankie’-style apologists for the Soviet regime.

Despite robust exchanges through the medium of the press, their friendship never suffered in the flesh – and I found the same to be true when I strongly disagreed with Martin’s comments about the Muslim minorities in the West after 9/11 – and indeed with his initial attitude to the “coalition of the willing” that then invaded Iraq and Afghanistan. He never took this personally – understanding intuitively, I think, that in a world where individuals such as ourselves have so little power, the line between posturing and being principled is a very faint one indeed.

And I think what he also understood only too well is that the line between life and death is also very a faint one – and easily crossed. It’s been gratifying even in the short while since his death, to see how many of his brilliant observations and remarks have been quoted. On ageing and death, he started early – and was preternaturally attuned to the dissolution of the body. Even with his first novel, superficially a youthful coming-of-age romp, his teenage hero is equating dental caries with inevitable dissolution. And by the time he published The Pregnant Widow in 2010, the intimations of mortality had become both clamorous and hilarious: “To cope with old age, you really needed to be young,” he has his protagonist say, “young, strong and in peak condition, exceptionally supple and with very good reflexes.”

The last time I saw Martin, in New York before the pandemic, we were talking about the parlous state of the contemporary literary scene – its preoccupation with content before style, with the identity of the writer rather than that of the text, and with profit above all. Martin said he thought the literary culture that had nurtured him would just about sustain him to the end, but that he doubted it would endure much longer.

Our mutual friend, JG Ballard, once observed that for the writer “death is always a career move” – so I say, bravo Martin, and while everyone who knew you at all well, and without exception, would wish you not only alive, but still typing away; nevertheless this, in common with so many others of yours, has been a brilliant career move.