If you ever took an art history survey in college, you may recall the blur of Fauvism. In the parade of projected images, it was the shocking flash of pure color that sped past as the course made its way to the more demanding rigors and longer shelf lives of Picasso’s “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon” and Cubism.

Fauvism, which lasted from about 1904 to 1908, is the first and probably the shortest of Modernism’s art movements. It is also one of the messiest, populated by a shifting cast of painters and locales. It lacks a manifesto or statement of goals, or even much stylistic coherence, and its tortuous buildup may have been longer than the trend itself.

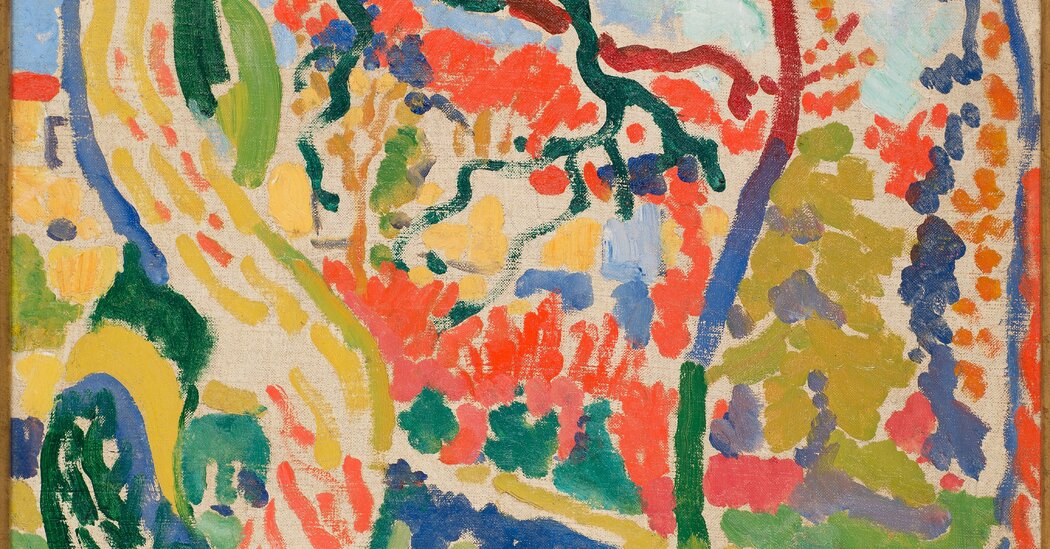

But in at least two ways the achievement of “les Fauves,” or “the wild beasts,” a term coined by the French critic Louis Vauxcelles — is foundational to modernist painting. It liberated color from merely describing reality — for example, green no longer equaled grass — opening the way to vivid colors that had a life of their own on canvas. The Fauves also freed artists from repetitious systems of paint handling — the dots, dashes and regular brush strokes of their Post-Impressionist predecessors including Seurat, Cézanne and even van Gogh.

With the exhibition “Vertigo of Color: Matisse, Derain and the Origin of Fauvism,” the Metropolitan Museum of Art cuts to the chase, narrowing the field to Fauvism’s two leaders, Henri Matisse and André Derain, and abstaining from the sprawling roster in previous Fauve exhibitions in New York. (The Met’s last treatment of the subject, “The Fauve Landscape” of 1990-91, included 125 works by 11 artists.) “Vertigo of Color” singles out what is perhaps the most important moment of Fauvism’s origins: when its radical nature — vivid color and seemingly crude surfaces, moving toward abstraction — came into public view and received its name at the Salon d’Automne of 1905, causing one of the most memorable art scandals of the 20th century.

This little arc of art history began only a few months before, in late June of 1905, when Matisse, one of France’s leading talents, invited his junior colleague, Derain, to join him in Collioure in the South of France. Matisse was summering with his wife and two sons and felt certain that the sun blazing on this small fishing village, the surrounding landscape and Mediterranean Sea would expose them to sensations and perceptions necessary to solve problems that had been plaguing them and other artists for several years. The chief problem was light: light in nature was superseded by the light inherent in the heightened artificial colors of paint, which the artists came to understand in the seemingly shadowless brightness of Collioure.

By the fall, when Derain and then Matisse left Collioure for Paris, they had produced more than 200 paintings, oil studies, pastels, watercolors and drawings.

At the core of this project, for better and worse, was painting as an autonomous object — and ultimately an abstract one. It had been identified in as many words by the painter and critic Maurice Denis in 1890, when he wrote that “a picture — before being a war horse, a nude, or an anecdote of some sort — is essentially a flat surface covered with colours assembled in a certain order.”

When the paintings of Matisse and Derain — along with the work of related talents like Derain’s one-time collaborator Maurice de Vlaminck — went on view in the Salon d’Automne at the Grand Palais, the public and not a few artists were outraged by the barbarity of the Fauvist works. It didn’t help that Vauxcelles, the critic, used the word “fauves” in his review. Although it was not necessarily intended to describe the artists, the name stuck. Other artists linked themselves to the trend; some, like Georges Braque, were inspired to take to it for the first time.

This radiant exhibition has been organized by the Met and the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and overseen at the Met by Dita Amory, curator in charge of the Robert Lehman Collection, and in Houston by Ann Dumas, consulting curator of European Art. It sets out to fix Fauvism, Matisse and Derain more firmly in mind, like Picasso and Braque are permanently affiliated with each other and with Cubism. It can be viewed, skeptically, as a branding endeavor, but it also clarifies the importance of Fauvism by focusing on its decisive growth spurt, at Collioure.

“Vertigo of Color” is not without problems: The main one is that Derain, the lesser-known figure, too often gets short shrift. The artists are fairly equal in paintings (18 Derains to 22 Matisses). But the discrepancy in works on paper (two Derains to 18 Matisses) throws things off — especially since the Matisses include several quietly stunning watercolors.

It may also be that the show, on the lower level of the Lehman Wing, deserved more space than the four hallway-like galleries that wrap around the inner court. It feels a bit wonky or unstable in parts. Some of this comes from the fact that Matisse and Derain were experimenting, trying out different ways of applying paint. There’s an approach-avoidance rhythm. Derain, for example, reverts to a startlingly conventional portrait of Matisse’s wife, Amélie — who sat regularly for both painters — as if he didn’t want to get too innovative depicting his mentor’s spouse.

The galleries devoted to each artist are fine, but leave you wanting more. One of the thrills of the Derain section is watching him discover another conveyor of light: bare canvas, which adds an essential sparkle.

Without white, or bare canvas, Derain’s paintings can get a bit claustrophobic. As chinks and patches of white start showing through, the paintings come to life. The use of bare canvas is fully realized in “Mountains at Collioure,” one of his best-known paintings, where the balance of the shapes of tree, leaves and hills are so carefully calibrated that the composition can initially dazzle and then become predictable, not unlike an appliqué quilt. Nearby, “Environs of Collioure,” a visibly “wilder” mix of electric colors and bare canvas scintillates and is one of the very best Derains here.

The works in Matisse’s section are never at a loss for balance. He seems at ease with space around all kinds of dots, even the Pointillist ones in the 1904 oil study for “Luxe, Calm et Volupté” lent by the Museum of Modern Art (the finished work, in the Musée d’Orsay, tightens up and is less successful). Next to it is a watercolor study for “The Joy of Life,” a glowing scene that defines its grove of trees in a series of widely spaced dabs of yellow and light brown. An oil study for “Joy” is equally good — and unpopulated.

There are Fauvist classics here, like “Open Window, Collioure,” a painting so widely loved and reproduced that it has become cloying. But there are also surprises, like four small scrumptious little landscapes and shorescapes from 1906.

In the show’s remaining sections, Derain all but disappears. His cautious portrait of Mme. Matisse is followed by several depictions of the wife by the husband — wonderfully sketchy watercolors and paintings in which, disturbingly, she is sometimes lost in the surrounding patterns of flora or tide pools. But Derain returns with a strong ink drawing that portrays Matisse sketching his wife on a rocky shore. In the portrait section, Derain is, again, scarce, but contributes an astonishing portrait of his mentor — his face painted in a way that resembles one of Bruce Nauman’s clown videos.

Fauvism began to fade by 1907, the year of Picasso’s “Demoiselles.” The show’s last view of Derain, who never returned to Collioure, is “The Palace of Westminster,” 1906-1907, one of his masterly Thames-side views of London. But soon he reversed course completely, to brown tones in still lifes that are full of asides to Matisse, Cubism and the old masters — and deserve their own exhibition. (Consider two marvelous little-seen examples in New York: the Met’s “The Table” from 1911, and MoMA’s “Window at Vers” from 1912.)

Fauvism would become the underpinning of Matisse’s life’s work. We see it gaining authority in his 1907 “View of Collioure,” one of the Met’s greatest undersung Matisses, usually confined to the Gelman Collection galleries. In it, giant flat leaves of deep green levitate around sinuous black trunks against a lavender sky. Matisse returned to Collioure every summer until 1914, suggesting a kind of pilgrimage. He was fully conscious of what he and Derain had wrought there. “Fauve painting is not everything,” he said, “but it is the foundation of everything.”

Vertigo of Color: Matisse, Derain, and the Origins of Fauvism

Through Jan. 21, 2024, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1000 Fifth Avenue, Manhattan, 212-535-7710; metmuseum.org.