By Danièle Cybulskie

If you’ve ever taken a look at medieval art, or wandered around a cathedral with visible tombs and monuments, you’ve most likely noticed that there are a whole lot of spooky images appearing from about the fourteenth century on.

Not surprisingly, in the years following The Black Death (c. 1346-1353 CE), which killed approximately one-third of Europe’s population, there was a trend in medieval art that highlighted looking death in the face, rather than shying away from it. Many artists created images and sculptures that ask the living to “remember death” (memento mori): that it is always waiting, and that it spares no one. In honour of All Hallows’ Eve, let’s take five minutes to look at how death was expressed in art in the late Middle Ages.

1. Corpses

This is a fairly obvious one, but it’s amazing how creative people got on the corpse theme. Rather than just skeletons, you can find images of corpses in various states of decay, and some of these are very prominent, like those you find on cadaver (or transi) tombs. Cadaver tombs feature, instead of (or along with) a flattering effigy of the deceased, a decomposing corpse. Here’s a good image of a cadaver tomb, this one of John FitzAlan, Earl of Arundel, at the Arundel Castle chapel.

2. Frogs, Toads, Worms, and Snakes

As if it weren’t enough to create an image of a corpse to make people consider their own mortality, medieval people also added the creatures that feast on corpses – or so they thought. If an artist wanted to be particularly gruesome, he would add toads, frogs, worms or snakes. Although these creatures (with the exception of worms) aren’t usually found feeding on corpses in nature, they were associated with evil (think: Garden of Eden) and death at the time.

You can find images of feasting creatures on the effigy of Francois I de la Serra, and in this image from the British Library.

3. Protesting Mortals

Naturally, even though medieval people were encouraged to contemplate death, that didn’t mean they actually welcomed it. Memento mori images frequently feature death or his minions coming for an unwilling victim. Often, the mortal is showing his or her reluctance through body language, as in this picture, but sometimes, there are words, too.

In this British Library image, death is actually impaling an understandably distressed person.

4. Demons at the Deathbed

Since memento mori and related images were created to encourage people to think about death in terms of Christian salvation, there are plenty of demons to be found in medieval images of death, particularly in deathbed scenes. For example, here are demons tempting the sinner in his last moments, and distracting the ill man from the counsel of the angels. Demons were thought to be always at the ready to drag sinners down to hell.

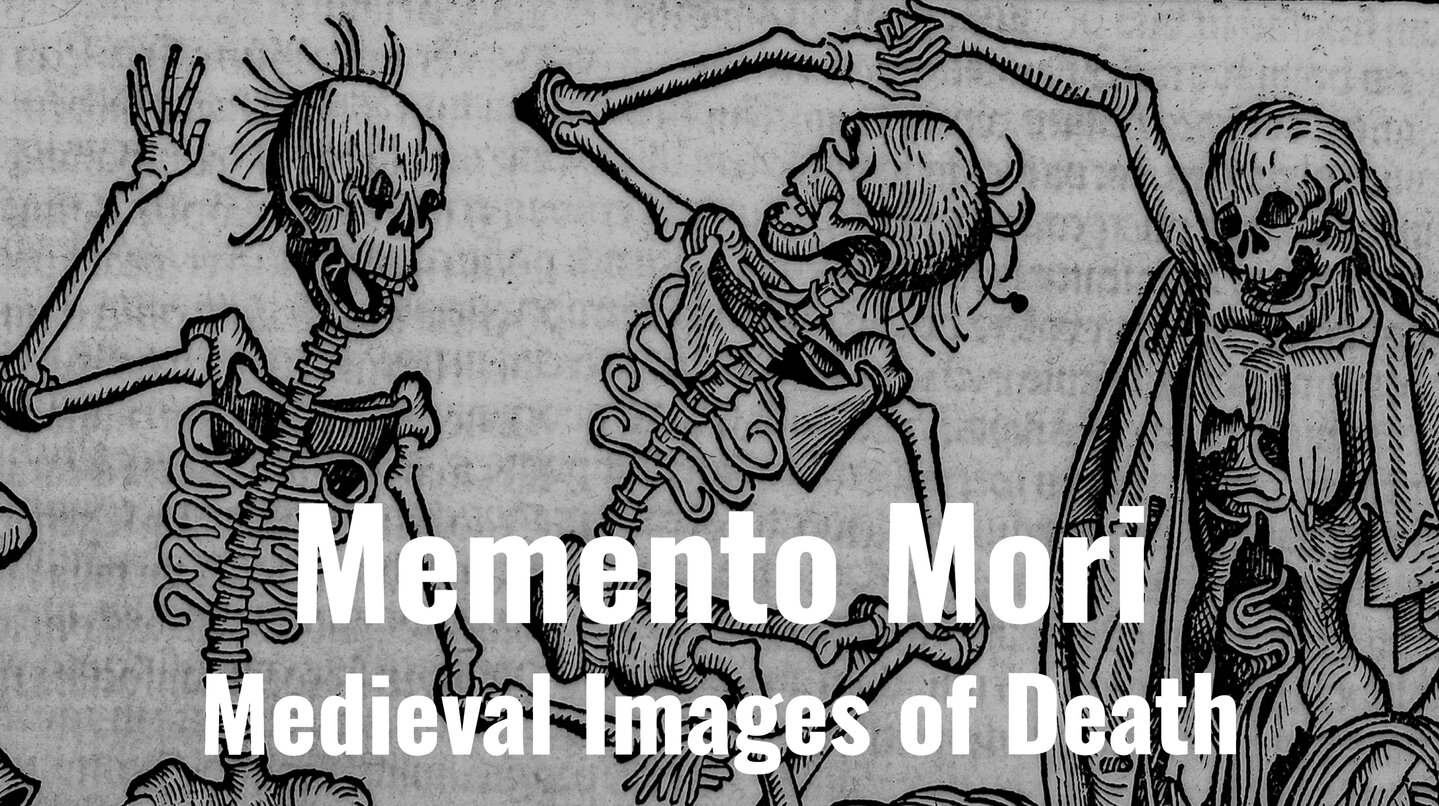

5. Dancing Skeletons

A popular and lasting image of death and dying that you can find in the late Middle Ages is the Danse Macabre or “Dance of Death”. In these images, death is merry, ever eager to pull people into the dance. The Danse Macabre often features many dancing skeletons, such as in this wall decoration.

Sometimes, the skeletons are even making their own music.

Although we mortals aren’t looking forward to it, the skeletons in late medieval art have a great time dancing the Dance of Death.

While death imagery was ultimately meant to urge a sinful public to contemplate eternity and repent, medieval artists took a certain glee in reminding viewers that death comes for kings, clergy, and commoners alike, something that The Black Death taught them all too well. This month, memento mori and All Hallows’ Eve both give us opportunities to contemplate the relationship between life and death for commoners and kings, but only one of these, sadly, is accompanied by tasty treats.

Danièle Cybulskie is the lead columnist of Medievalists.net and the host of The Medieval Podcast. She studied Cultural Studies and English at Trent University, earning her MA at the University of Toronto, where she specialized in medieval literature and Renaissance drama. You can follow her on Twitter/X @5MinMedievalist or visit her website, danielecybulskie.com.

Click here to read more from Danièle Cybulskie