In “Fisherman in a Red Shirt”, a luminous oil painting by the Georgian “tavern painter” Niko Pirosmani, a man with his catch gazes at the viewer, a river swirling at his ankles. The contrast between his momentary stillness and the flowing water, the blaze of scarlet cloth against pitch black, gives him the intensity of an icon — his broadbrimmed hat a halo. Up close, the image reveals itself as conjured from minimal white or yellow brush strokes on largely untouched oilcloth. As the Polish-Georgian avant-garde artist Kirill Zdanevich marvelled in “awe and confusion” in 1912: “This style of art requires incredible talent.”

Georgia’s most popular artist today, Pirosmani was until recently little remembered outside the former eastern bloc. Following surveys at the Albertina in Vienna and the Van Gogh Foundation in Arles, Niko Pirosmani at the Beyeler Foundation in Basel is the largest international exhibition to date. Curated by Daniel Baumann in Renzo Piano’s white-cube expanse, it affirms his place at the birth of European Modernism, stripping away an accretion of myth, ideology and even kitsch, to reveal just what arrested the eye of the rising avant-garde.

This solo show coincides with the first major survey of The Avant-Garde in Georgia (1900-1936) at the Centre for Fine Arts (Bozar) in Brussels. Part of Europalia Georgia, a timely cultural season across Belgium, it includes eight Pirosmani paintings to highlight his catalytic effect on Georgian Modernism. This artistic starburst in Tiflis (now Tbilisi) was doomed by Soviet invasion in 1921, and all but expunged from memory by Stalin’s purges and Soviet rule. Yet together, these shows unearth a buried chapter of European art history, just as Georgia (in line for EU candidate status in December) may be poised to rejoin the European mainstream and as Russia’s former colonies — like Ukraine — reassert their distinct cultural histories.

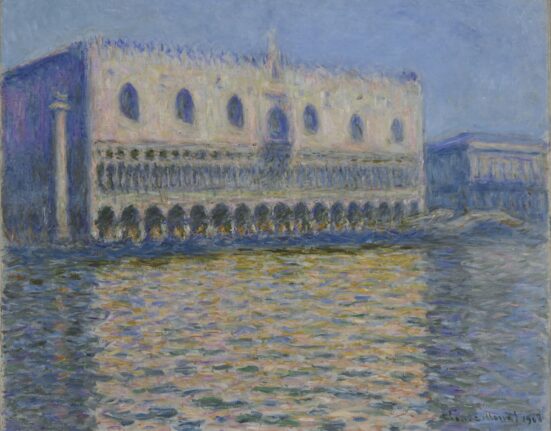

Pirosmani, a sometime sign-painter and Trans-Caucasus Railway brakeman, was “discovered” in a Tiflis tavern by Zdanevich and Mikhail Le Dentu, St Petersburg Art Academy students who likened him to Matisse or the “Georgian Giotto”. In 1913, together with Zdanevich’s younger brother Ilya (the Futurist “Zaum” poet, Iliazd), they had his paintings shown in Moscow alongside Marc Chagall, Kazimir Malevich and Natalia Goncharova. Yet Pirosmani was long dead before his work was unveiled at the Louvre in 1969 as that of a “naive Russian artist”, the “Rousseau of the east”, shortly before Picasso’s drypoint etching of 1972 (on show at Bozar) portrayed him as a maelstrom of lines at an easel.

Born in 1862 to a peasant family in Kakheti, eastern Georgia, where his single-storey house-museum is deep in wine country, the only confirmed photograph shows him in European dress (innkeepers called him “the Count”) with a tormented stare. Painting for a meal or vodka, he died a pauper in 1918. Many of the 46 works at the Beyeler were saved from oblivion by the Zdanevich brothers and are on loan from the Museum of Fine Arts in Tbilisi.

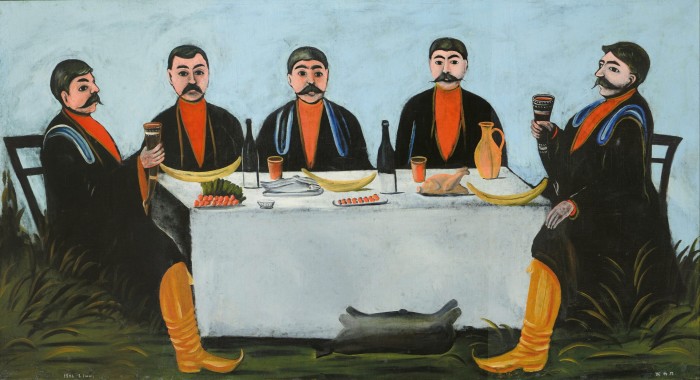

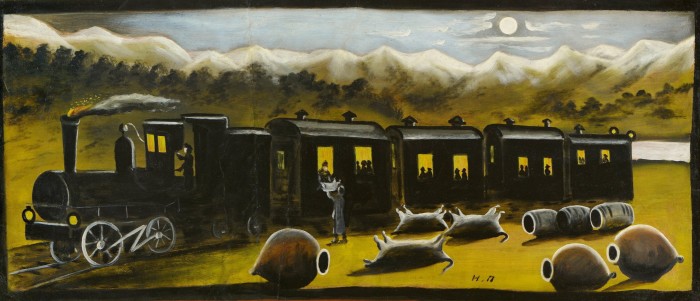

On tin, cardboard, oilcloth and canvas, they range from feasts and enigmatic landscapes to animal paintings such as “Bear on a Moonlit Night”. In “The Kakhetian Train”, redolent of Magritte, hawkers offer wineskins to passing night-train passengers amid surreally moonlit mountains. Painting brigands and nobility alike, Pirosmani turned social observation into parable, or reclining sex workers into saints in the “Ortachala Belle” diptych. “Roe Deer and Landscape” resembles portraiture as the subject holds our gaze. “Arsenal Hill at Night” — sold at Christie’s in 2015 for more than $1.5mn — is key: rustics warm their hands at a bonfire while the distant city glows with electricity. Pirosmani was a “man between worlds”, says Baumann, who likens his universal appeal to Chagall and Warhol. “The old Tbilisi is disappearing, and the industrial world is coming.” His figures “float between worlds”.

A contextual room, designed by the Georgian installation artist Thea Djordjadze, has photographs of Tiflis, both “Asiatic” and European. While Pirosmani was caricatured in 1916 as a barefoot primitive, Irine Jorjadze, co-curator of the Bozar show, senses a colonial disdain for the Caucasus “as wild, brutal nature”. Yet, adopted as a young orphan by a noble family in Tiflis, Pirosmani read in both Georgian and Russian. He mined Christian and Islamic iconography. Janus-faced, the Silk Road city offered sources from Byzantine frescoes and Persian miniatures to Parisian postcards. “His art was not born out of nowhere,” Ana Shanshiashvili remarks in the Beyeler catalogue.

In the 1930s, Pirosmani was restyled as a hero of the people destroyed by the bourgeois Mensheviks. He was then forgotten until the 1960s. He was “rediscovered many times”, Djordjadze says, with “propaganda about this ‘naive’ Georgian artist; it’s an imperialist way to diminish him”. For her, “the Soviets used him to overshadow the whole Modernist movement of the 1910s and ’20s.”

That movement at last gets its due at Bozar. Superbly curated by Nana Kipiani, Tea Tabatadze and Jorjadze, with input from the artist Levan Chogoshvili — and art and archive dating back to the 1830s — the show and catalogue uncover Georgia’s synchronicity with international art movements, suggesting how it fed eastern currents into European Modernism. This chapter was unearthed by Soviet dissident artists such as Chogoshvili, whose Dada collage map “The Donkey’s Way” (2018) is the opening work. Tiflis at its centre is linked to Rome and New York — all cities at 41 degrees north. A row of tiny donkeys alludes to Iliazd’s Zaum texts.

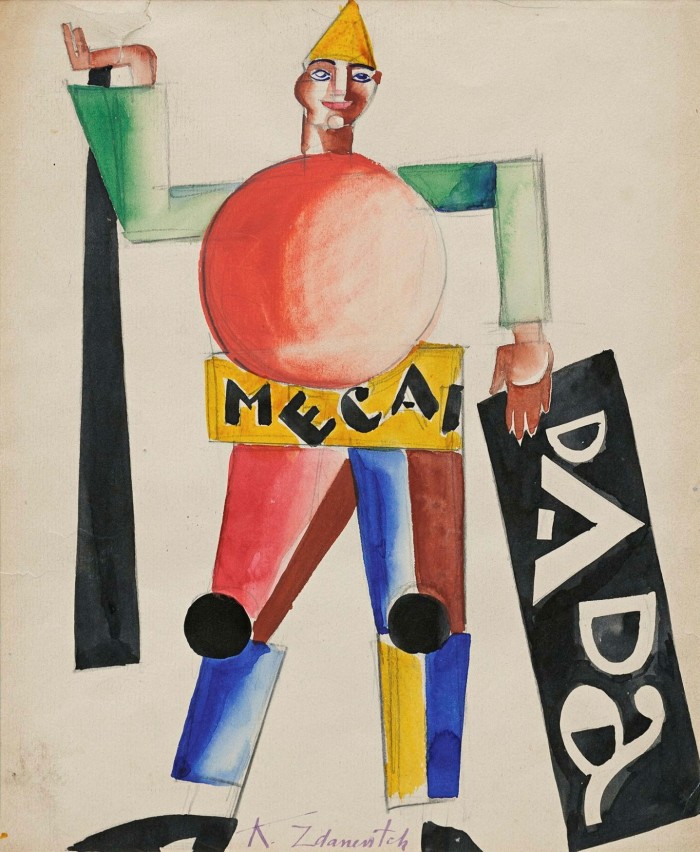

Photographs offer tantalising glimpses of Modernist artistic cafés of 1917-21, when Tiflis became a refuge for artists fleeing revolution and civil wars across the Russian empire. This multilingual crucible of movements such as Cubo-Futurism and Dadaism reached its zenith during the Republic of Georgia of 1918-21, a heady interlude between tsarist and Soviet rule. Young artists who championed Pirosmani made café murals whose remnants survive: Lado Gudiashvili’s “Stepko’s Tavern” and Davit Kakabadze’s “Artist and Muse” were painted in 1919. Kirill Zdanevich’s superb sketches include “Old Tbilisi” (c1920), an ink drawing of café musicians, and a 1924 theatre costume for a colourful harlequin.

Pirosmani’s shop signs (one here is for “cold beer”) fed the Modernist use of lettering and the radical typography of Iliazd, who co-founded the magazine 41° in 1917. In a vitrine are some of the 50 avant-garde books published in Tiflis in 1918-21. After the Red Army invaded, Iliazd settled in Paris, working on artists’ books with Picasso and others, and textile design with Coco Chanel. For decades, until 1966, he and his brother (who spent years in the Gulag) were kept apart.

An overwhelming sense of doom and waste pervades later rooms. Modernists sought refuge in theatrical and cinematic set and costume design, with vibrant sketches, maquettes and footage. Yet artists who rode out uprisings and purges were broken by the diktats of Socialist Realism. Kakabadze’s vibrant patchwork landscapes give way to lifeless vistas incorporating Stalin billboards and hydroelectric dams.

Among the defiant was Petre Otskheli, whose expressive oil painting, “Torso of Man” (1925), evokes a tortured soul. His 1930s sketch for the film The Flying Decorator is beside a 1934 poster with his name sliced out. Otskheli was among artists executed in Stalin’s Great Terror in 1937. He was 30.

“To be able to see,” Pirosmani told the elder Zdanevich, “one should not have eyes blurred with prejudice.” Both these shows will open eyes.

Bayeler Foundation, Basel, to January 28, fondationbeyeler.ch. Centre for Fine Arts (Bozar), Brussels, to January 14, bozar.be. Europalia Georgia, europalia.eu

Follow FTWeekend on Instagram and X, and subscribe to our podcast Life and Art wherever you listen