A series of discoveries is revealing that Europe’s first inhabitants settled in a remote and rugged corner of Granada some 1.4 million years ago.

N

Nestled in the heart of the High Plateau of Grenada in southern Spain, the 1,300-person town of Orce is surrounded by a tapestry of dry badlands, deep canyons and crystal-clear reservoirs that extend as far as the eye can see. Few travellers venture to this remote corner of Andalusia, but those that do are granted a fascinating glimpse into Europe’s past.

If you take the winding road 140km north-east from Grenada, past the serrated ridges of the Sierra de Huétor Park and the arid steppe plains of the Sierra de Baza Park to Orce, you’ll soon discover that this unassuming hilltop hamlet guards a unique secret: it is believed to contain the remains of the earliest humans on the continent. In fact, the archaeological discoveries in this rural region not only reveal glimpses of where Europeans came from, but how different the natural world was when humans first stepped foot on the continent.

“Stones that resemble bones”

In 1976, a local farmer named Tomás Serrano began stumbling upon what appeared to be fossilised remains in his fields. Recognising the potential importance of his discoveries, he showed them to neighbours and relatives, explaining that he had found “stones that resemble bones”. When he contacted local authorities, they didn’t give much importance to his findings. But when three members of the Catalan Institute of Paleontology later travelled to the area and examined Serrano’s findings, they confirmed that his hunch was correct: these were no ordinary stones.

Serrano’s farm and the surrounding area soon became a working archaeological site, and as a team of experts descended near Orce in the coming years, they discovered a continuous presence of fossilised remains of large mammals dating back approximately 1.5-1.6 million years. This fossil layer formed in an environment of freshwater ponds, near the ancient Lake Orce-Baza, where the bones were deposited by and buried in the calcareous mud that was covering them.

A startling discovery

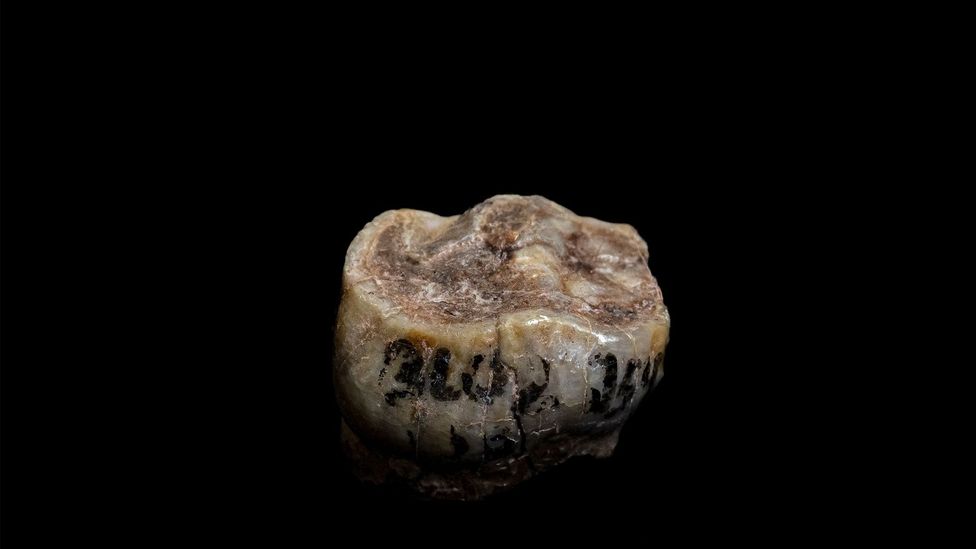

As archaeologists continued digging in the region, they made a startling discovery in 2002 at Barranco León, located about four kilometres away from Serrano’s farm. There, buried in the western slope of a ravine 14m below the surface, the team came across the fossilised remains of a child’s tooth. After extensive testing methods (including electron spin resonance, paleomagnetism and biochronology), experts confirmed that the molar dates back a staggering 1.4 million years, making it the oldest Homo genus remains on the continent.

The tooth, carefully excavated from the layers of sediment, belongs to a child who lived at a time when humans are believed to have just started making fire. This tiny artefact holds within it the traces of a far-flung world: a child’s toothy smile frozen in time, in an era when our distant ancestors were hunting prey while simultaneously trying to avoid being hunted.

A glimpse of a far different Europe

One of the most fascinating aspects of the fossilised finds from the Orce region is that they not only reveal glimpses of humans’ distant past, but also that of southern Europe’s ancient landscape. Roughly 1.6 million years ago, a substantial lake known as Orce-Baza dominated portions of this region. When it receded, fresh groundwater took its place, leading to a diverse array of creatures to thrive here. Mammoths, hyenas, sabre-tooth tigers, hippos and deer all coexisted in this ancient landscape, alongside Europe’s first hominids of the Homo genus.

According to Juan Manuel Jiménez Arenas, a paleoanthropologist and the director of the ORCE Project, “The biodiversity of this site is comparable only to that found in the great African parks of today. And looking at the almost desert-like lands, it is hard to imagine that hippopotamuses frolicked here and that large, short-faced hyenas rested under wild olive and oak trees near freshwater ponds.”

“The Silicon Valley of prehistoric times”

As excavations continued in the years ahead, archaeologists discovered additional findings that startled them: not only was Orce found to contain the oldest human remains in Europe, but the people that inhabited this area some 1.4 million years ago appeared to have used highly innovative techniques to make their stone tools that wouldn’t be used again for another 400,000 years, leading experts to declare this site “the Silicon Valley of prehistoric times”.

At the centre of this discovery are spherical-shaped stone balls known as spheroids. These intriguing limestone tools denote high cognitive abilities, a knowledge of geometry, as well as the physical characteristics of the raw materials used. To achieve these carved tools, early humans had to look for the appropriate raw material (fine-grained limestone) and conscientiously plan each of their strokes with a hammer-like object. Experts believe the carvers at Barranco León had a preconceived idea of the final product, very fine motor skills and a hierarchy of carving gestures.

A veritable outdoor museum

Thanks to its prehistoric significance and remarkable geological richness, the area of Orce was recognised in 2020 as a Unesco World Geopark. Additionally, the region boasts several museums dedicated to prehistory, including the Primeros Pobladores de Europa (First Settlers of Europe) museum in Orce. Here, visitors can marvel at the innovative stone tools used by our ancestors and the awe-inspiring bones of mammoths. Another notable site is the Piedra del Letrero in the nearby village of Huéscar, a renowned cave containing elaborate paintings. The vivid red depictions of animals and figures date back more than 6,000 years, offering a fascinating glimpse into ancient times.

There are also several companies that offer guided tours of the High Plateau of Grenada – from the local archaeological museums into the mountains – allowing people to follow the traces of Europe’s earliest inhabitants. Especially on weekends, the surrounding badlands and rugged limestone mountains attract numerous cyclists and hikers eager to explore this hidden corner of Spain. Even in winter, when the biting wind and low temperatures set in, enthusiasts brave the elements, heralding the onset of the ever-welcome snow.

Modern-day cave houses

Eight kilometres west of Orce, the village of Galera emerges as a captivating testament to the past. Here, thousands of cave houses, hewn into the bedrock and hills, whisper stories of a bygone era. These houses, with a troglodytic and prehistoric origin, are believed to date back to the Moorish era (beginning in 711 AD). Today, these caves not only serve as contemporary dwellings, but also stand as a living connection to the enduring history of the High Plateau region – weaving a seamless thread from antiquity to modern times.

For adventurous travellers, these caves provide an immersive lodging and cultural experience. With panoramic views and curated interiors, each cave house tells a story of resilience and adaptation. Beyond its archaeological significance, the region’s small towns enchant visitors with their many cobblestone streets, quaint cafes and local markets, providing a taste of traditional Spanish culture. This is also one of the best places to try the area’s famous cordero segureño, a local sheep connected to the shepherds of this region.

The trail of first settlers of Europe

From Iberians to Romans to Muslims, wave upon wave of different people and cultures eventually followed these first humans here. They each found a home in this rugged landscape while also making their mark on it. One way to understand and experience this layered history first-hand is to embark on the Great Path of the First European Settlers trail: a 143km itinerary that’s allows travellers to trace its length by car, bicycle or on foot.

The route passes through the towns of Huéscar, Castril, Castilléjar, Galera, Orce and La Puebla de Don Fadrique. The imposing La Sagra (2,383m) mountain dominates the horizon of the trail, and the journey itself is a scenic adventure through the traditional Andalusian countryside. Whether on two wheels, four wheels or on foot, this is a region to absorb slowly, allowing for spontaneous detours to centuries-old villages to discover hidden treasures along the way – many of which are still being unearthed.

BBC Travel’s In Pictures is a series that highlights stunning images from around the globe.

—

Join more than three million BBC Travel fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter and Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter called “The Essential List”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

;