The icon indicates free access to the linked research on JSTOR.

While the stereotype about the Middle Ages is that it was an era of darkness and filth, medieval art and literature suggest the opposite—it was a colorful epoch, even bright—during which people delighted in bathing and appreciated its medicinal value.

Bathing for Health

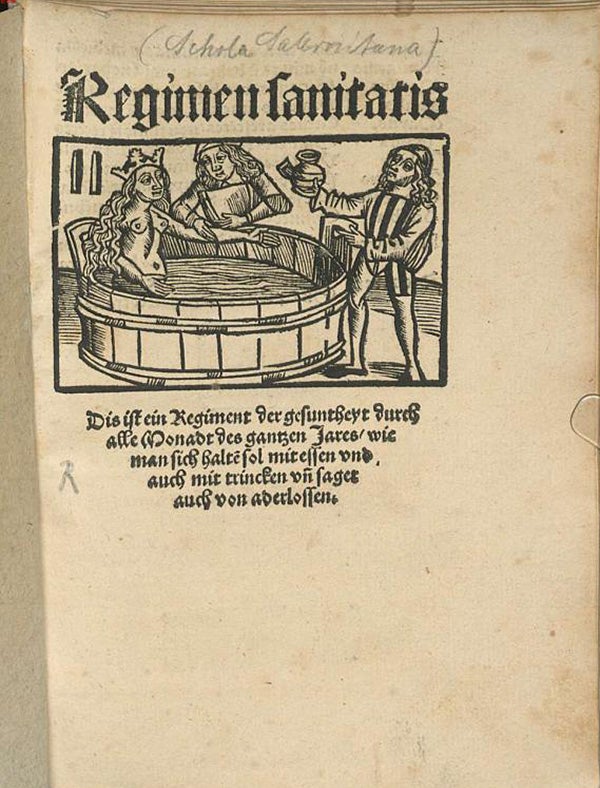

That bathing is critical to maintaining good health has been known since antiquity. Throughout history, both medical treatises and poems have been dedicated to the subject of good hygiene. Regimen Sanitatis Salernitanum, a Latin poem made up of more than 360 rhymes was likely first written in the eleventh century by someone familiar with the education provided by the medical school in Salerno. Later translated into various vernaculars, the popular poem offered common sense advice on how to keep well by, for example, washing hands and face in cold water in the morning, and taking care to keep warm after a bath. Indeed, an early German print of this poem featured a woodcut of a queen bathing.

A later version of Regimen Sanitatis Salernitanum is attributed to Milanese physician Maino de Maineri (d. 1368), who was educated in Paris and worked in royal courts throughout Europe. He also wrote some fifty recipes for bath solutions, customized to individual needs.

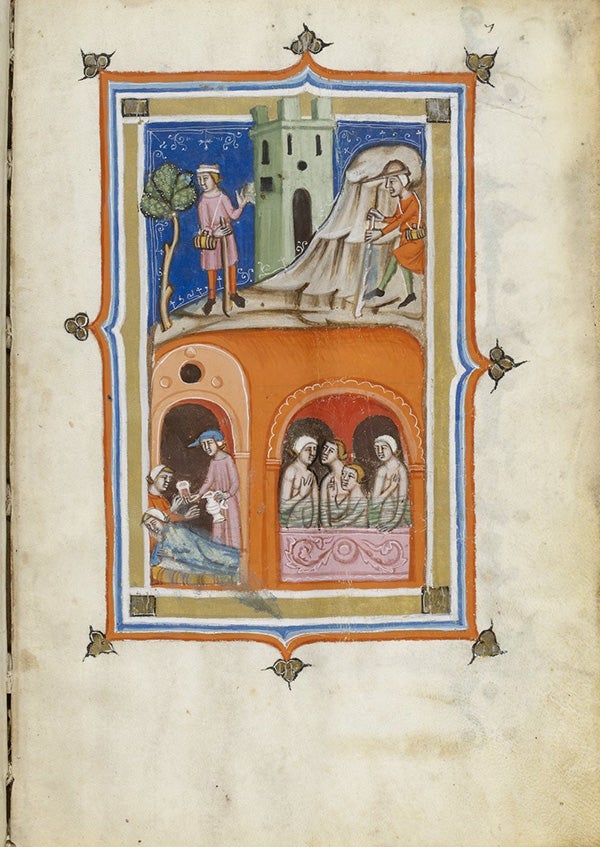

De Balneis Puteolanis (“Of Baths in Pozzuoli”) by Peter of Eboli, is another Latin poem dedicated exclusively to baths, written in the early thirteenth century. Peter of Eboli described thirty-five ancient baths around the Bay of Naples, home to thermo-mineral springs. Medieval manuscripts of this poem feature illustrations of bathers in indoor pools as well as in caves, enjoying steam baths, relaxing, drinking mineral water, and taking it away in small barrels.

Ancient Romans associated the town called Baiae (a spa resort also in the Bay of Naples) with Venus, the goddess of love, while medieval astronomical manuscripts depicted people born under the influence of the planet Venus as bathing in the Fountain of Youth. A Eurasiatic myth about a miraculous fountain whose waters reverse the aging process mirrored this idea, and the development of vernacular literature during the Crusades spread this myth. Largely popularized by the Roman d’Alexandre, the motif of the Fountain of Youth was common in late medieval courtly culture. Luxurious ivory caskets and mirror frames, for example, were decorated with images of it. The restoration of youth became synonymous with the restoration of libido and sex appeal, and indeed there are examples of medieval wall-painting that showed those entering the fountain in pursuit of youth engaging in intimate behavior.

Bathing for Seduction

The importance of hygiene in reference to the art of seduction is rooted in ancient texts. In Ars Amatoria (The Art of Love, from the early first century BCE), Ovid stresses the importance of women taking care of themselves:

“A careful toilet will make you attractive, but without such attention, the loveliest faces lose their charm, even were they comparable to those of the Idalian goddess herself.”

Writers of the medieval period were inspired by Ovid. In the thirteenth century, for example the Frenchman Jean de Meung adapted lines from Ars Amatoria in his part of the allegorical Le Roman de la Rose (The Romance of the Rose), which reveals that elegant ladies are expected to keep their pubic areas hair free:

“If she’s well brought up, I’d say,

All the cobwebs she’ll sweep away,

Scour and trim, and smooth and gloss,

So that naught can gather moss.”

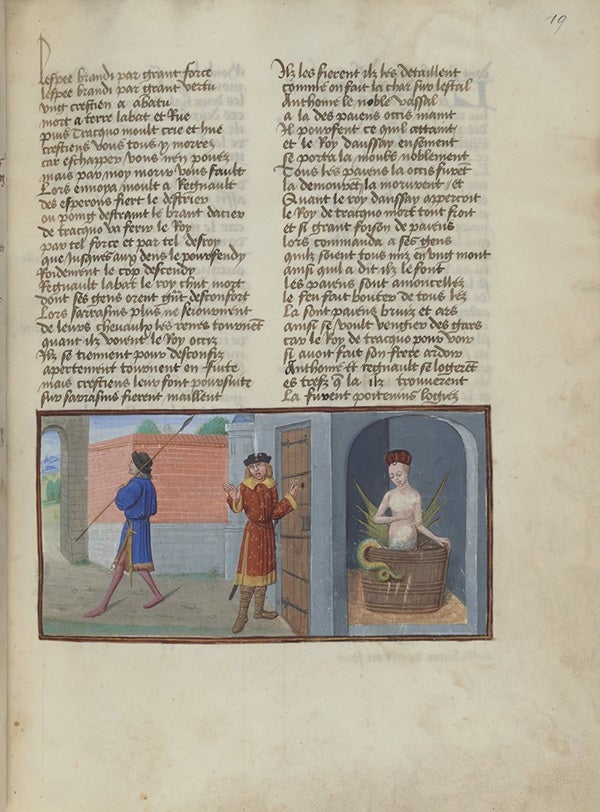

The twelfth century legend of Mélusine, known best through Jean d’Arras’ Roman de Mélusine, from the fourteenth century, also includes information about contemporary bathing habits.

After being cursed by her mother, Mélusine is doomed to become a serpent from the waist down every Saturday. She marries Raymondin on the condition that he promises to avoid looking at her on Saturdays, when she takes her bath. Only years later does Raymondin, suspecting Mélusine of adultery, break his promise and discover her secret. The legend demonstrates how commonplace it likely was for many noblewomen to spend an entire day on hygiene, reflecting the importance of bathing as a practice.

Bathtime Fables of Kings

Kings, too, spent considerable time performing ablutions.

In Vita Karoli Magni (Life of Charlemagne), the ninth century Frankish scholar Einhard observed that Charlemagne invited his sons and friends to join him in a pool-like bath. Members of his court as well as soldiers were likewise welcome, and at times, more than a hundred men bathed together. Indeed, baths with spacious pools were an important feature of Charlemagne’s palace in Aachen. Their thermal complex, Aquae Granni (“Waters of Grannus,” a reference to a Celtic healing god associated with medicinal springs), existed since the Roman era and inspired the later Latin name of the city: Aquisgranum.

Wenceslaus IV of Luxembourg (1361-1419), the king of Bohemia (and, for a time, Germany) was one of Europe’s most famous bath-loving monarchs. According to a sixteenth century legend, Wenceslaus escaped prison with the help of Susanna, a bath attendant, who became his mistress. He, in turn, gave her a bath house to run in Prague. Whether this story is apocryphal, there is no disputing that Wenceslaus enjoyed a good soak. In the holdings of the Austrian National Library, a magnificent, unfinished six-volume manuscript of the Bible is decorated with more than 1200 parchment folios, many of which offer erotic depictions of bath attendants serving King Wenceslaus.

Around that time, Władysław II Jagiełło (d. 1434) ruled Poland. The Grand Duke of Lithuania, he was crowned king after marrying Jadwiga of Anjou (d. 1399). They ruled as co-monarchs, and their marriage led to the union of their countries as well as to the Christianization of Lithuania. As noted by historian Jan Długosz (d. 1480), young Jadwiga was disturbed by the prospect of marrying an unknown older man of pagan background. She sent a trusted knight, Zawisza of Oleśnica, to meet her intended and determine that he was not what she feared —a hirsute wild man. Jagiełło was clever enough to understand the delicate nature of Zawisza’s mission, and invited the knight to join him in the bathhouse where Zawisza saw Jagiełło unclothed and could then assuage Jadwiga’s concerns.

In fact, King Jagiełło was said to be obsessed about cleanliness: he had private baths built in the house near Wawel castle in Cracow. The castle was built on top of Wawel Hill; the baths were located at its foot, as they needed to access water running down. It wasn’t until the sixteenth century when running water was delivered through pipes directly to the chambers of the royal castle up on the hill.

According to Długosz, Jagiełło bathed at least every third day. This may had been regarded as excessive; most people bathed weekly, like Mélusine, but bathing was not the only way to maintain hygiene. Late medieval religious artworks illuminate what would have been contained in the interiors of a typical bourgeois home at that time: the fifteenth-century Netherlandish depictions of the Virgin with a Child, for example, show washing implements and towels on racks. These items may well serve dual purpose; they symbolize Mary’s purity, but also depict household items typical of the time.

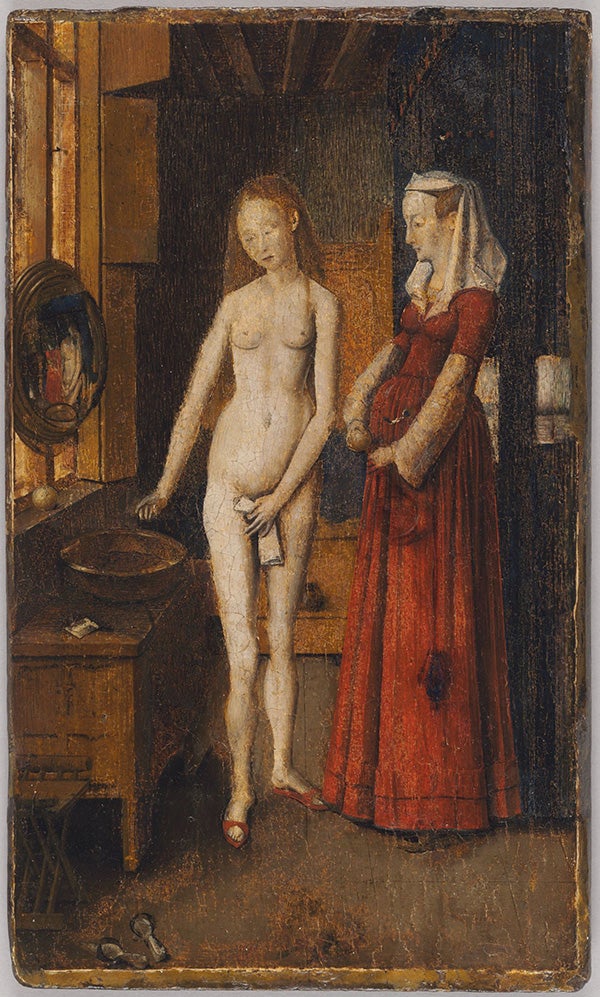

A painting in the collection of the Fogg Museum at Harvard University offers an illuminating depiction of such implements. The anonymous work dates from ca. 1500; it is likely a copy after a lost masterpiece by Jan van Eyck (d. 1441).

The painting depicts a naked woman, washing herself; she is accompanied by another woman, fully dressed, most likely a handmaiden. That is how wealthy ladies cared for their bodies: their servants drew their baths, washed their bodies, brushed their hair, and applied ointments to their skin. It was not considered awkward or improper to undress completely in the presence of a servant.

Bath and the City

Ordinary people in medieval cities bathed regularly in public bathhouses. These were often built close to bakeries, to share heat produced by the ovens. Public bathhouses offered regular tubs, steam baths, massages, shave and haircut services, as well as medical procedures including simple wound dressing, cupping therapy, and bloodletting. That bathhouses offered such a menu led to conflicts between their owners and local barbers and surgeons, who accused the bathhouse owners of poaching clients. Bathhouse owners were largely undeterred; some went further, providing food and live performance.

Late medieval Cracow was home to twelve public bathhouses. Legal regulations imposed at the time suggest bath houses served purposes besides hygiene; bath attendants, for example, were forbidden to prostitute themselves, and it was forbidden to tip any entertainers. Bath houses were used by everyone. Workshop masters were obligated to have their employees bathed at least once in a fortnight. Some benefactors funded baths for the poor as a form of charity.

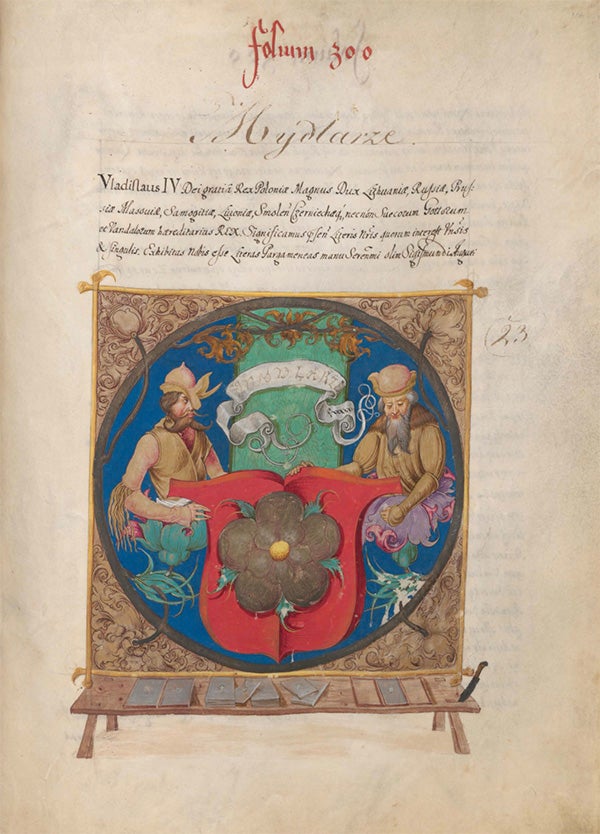

As all the other craftsmen in medieval cities, bath workers had their guild, as did soap makers. The Baltasar Behem Codex, an early sixteenth century Cracow cartulary, offers unique related iconography. It features extraordinarily decorated miniatures portraying representatives of various crafts. One such images shows two soap makers holding up a shield with a rose—their guild’s coat of arms. Rectangular soap bars are displayed on a wooden table, in the lower part of the miniature artwork.

By the sixteenth century soap production flourished in Cracow. Soap-makers from the satellite towns of Kazimierz and Kleparz, the former the home to a Jewish community and a mikveh (Jewish ritual bath), repeatedly applied for permission to establish their own guilds.

The Myth of the Dirty Middle Ages

In spite of all this, the myth of the Dirty Middle Ages arose and persists in part because of the writings as well as the legends of saints. St Bernard of Clairvaux, for example, asserted that the Knights of Christ should “seldom wash and never set their hair,” a directive that was taken out context and which, in fact, instructed people to forsake worldly vanities. Hedwig of Silesia (1174-1243) and Kinga of Poland (1224-1292), both Polish saint duchesses, were known to avoid bathing, and only occasionally wash their faces. For the saints, refraining from bathing was a form of ascesis: denying oneself a proper bath was considered an act of mortification of the flesh. That said, “Vita beatae Hedwigis” (1353, Getty, Ms. Ludwig XI 7) includes an illustration of a peculiar act of humility: Saint Hedwig washing herself and her grandson with water earlier used by the nuns to bathe their own feet.

Still, the saints were aware that hygiene was vital to good health. Saint Elizabeth of Hungary, who dedicated her life to serving the poor and sick, was often depicted bathing the ill, or cutting their hair.

The hygiene habits of people in the Middle Ages are often mischaracterized because in the subsequent Renaissance period there was indeed a significant abandonment of hygienic practices. This was likely due to the syphilis-induced mass closure of public bathhouses in the 1500s. As Erasmus of Rotterdam noted in the 1520s, within a quarter of a century almost all the public bathhouses in Brabant were shuttered because the new disease scared away clients. These closures changed the customs of entire societies, as common people started to address their hygiene within the confines of their own homes; household inventories indicate that bathing accessories gradually disappeared from wealthy houses throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

Ancient and medieval physicians believed that bathing and maintaining hygiene could have cured many diseases; alas, it was disease that was responsible for turning Europeans away from cleaning themselves regularly. If the clients of bathhouses enjoyed the same services as King Wenceslaus, it is perhaps unsurprising that a sexually-transmitted disease broke out. But leave the people of the Middle Ages out of it.

Support JSTOR Daily! Join our membership program on Patreon today.