Too many of us were looking the wrong way in the lead-up to the Brexit referendum. Like the New European itself, the satirical art of Cold War Steve and Led by Donkeys only emerged in the aftermath of the vote. Yet the rage and frustration that marks their presence on the post-Brexit landscape cuts all the more keenly for its late arrival, and is symptomatic of the reverberating disbelief haunting those who failed to anticipate such an act of self-harm.

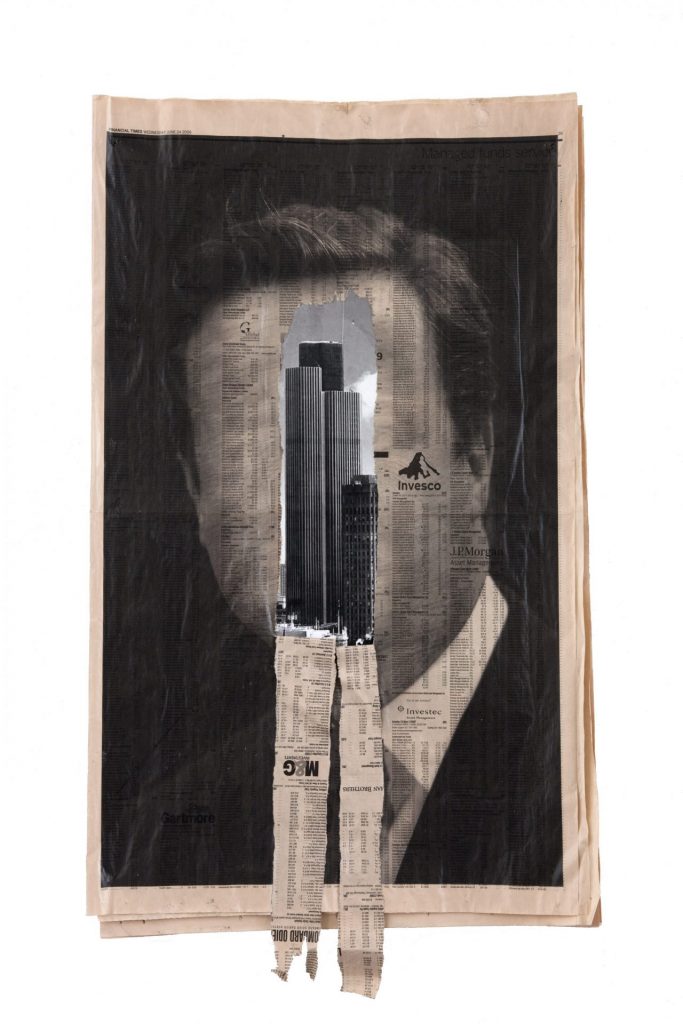

Appropriately enough, in the wake of a political campaign fought in the dirty battlegrounds of Twitter and Facebook, Cold War Steve’s sardonically captioned, trenchant photo collages came to notice on social media feeds; similarly the billboard campaigns by activist artists Led By Donkeys found a much larger audience online. Guerilla warfare by satire proved to be the only tactic capable of hitting back at such shameful episodes as Nigel Farage’s breaking point poster, which Led By Donkeys reworked in 2019, exposing the original for all its opportunistic mendacity.

In her book Leave to Remain: A Snapshot of Brexit, polymath writer and researcher Noni Stacey recounts the evolution of Cold War Steve, the nom de guerre of Christopher Spencer, whose time as a probation officer provided a crash course on “the impact and consequences of the government’s cruel austerity measures.” At first, his Twitter posts were “a joke of incongruity”, that had Eastenders’ Phil Mitchell (the actor Steve McFadden), putting in unlikely appearances next to Cold War leaders, such as US president Ronald Reagan, and Mikhail Gorbachev.

“Utterly distraught” over Brexit, Cold War Steve became a coping strategy. Spencer was well-equipped to make the shift, he told Stacey, since he had been following the architects of Brexit for some time, and was “accustomed to the endless bullshit sleaze.”

The modus operandi of campaign group Led By Donkeys is similarly born of a need to stem a rising sense of helpless frustration. Founded by Greenpeace employees Oliver Knowles and Ben Stewart, with James Sadri and Will Rose, who were previously involved with the charity, Led By Donkeys specialises in weaponising politicians’ words, on billboards, on the Houses of Parliament, and on the Home Office. On one memorable occasion, the White Cliffs of Dover provided the setting for a projection of Dominic Raab’s most conspicuous howler, when he admitted his failure to grasp the importance of the Dover-Calais Crossing.

These activist artists are among the most prominent voices railing against this government, but as the lukewarm efforts of the Remain campaign faded to nothing, the vacuum was filled by this newspaper, activist artists and campaigners and established artists like Cornelia Parker, Tacita Dean, and Banksy, who all refused to respect the omertà imposed by the Brexiteers.

British artist Tacita Dean campaigned to Remain, and as a German citizen who lives part of the time in Los Angeles, has considerable skin in the game. Her vantage point outside Britain has given her a particular clarity of insight, and she notes that British art institutions were fatally half hearted in their opposition to Brexit.

Stacey, currently a Practice Supervisor at Royal Academy of Art, The Hague (KABK), and Visiting Research Fellow at TU Dublin, has channelled her own rising dismay into a book that she calls a “work of personal protest”, a scathing condemnation of a government that “abhors scrutiny”, hijacked by unscrupulous “citizens of nowhere” who pushed so hard to make Brexit happen.

Stacey holds British and Irish passports, was born in Germany, has lived in the Netherlands, and is now based in Glasgow. The book, she writes, is also a manifesto, calling for “a return to working relations and trade with our closest neighbours”, but also “an archive of resistance” surveying the breadth and depth of artistic responses to Brexit.

That resistance has come not just from the margins, but from established figures in the art world, like Cornelia Parker, who in 2017 was the official artist attached to the general election. It reflects the extent of the wound inflicted, and the specific damage done to artists and the creative industries by curbs on freedom of movement, and the costs and bureaucratic load associated with touring. The impact of Brexit is explored in detail in interviews detailed enough to serve as case studies not just of artists, but of musicians and others, including a lawyer specialising in art, and a paintings conservator.

Combined with a cogent survey of the public discourse around Brexit, and the persistent myths of national identity that have shaped the UK’s longer-term relationship with the EU, Stacey’s book is an expansive account of the advent of Brexit, and its unfolding consequences. She finds its genesis in a slop bucket of decline, from the first referendum on Europe in 1975, to the toxic breeding grounds of the Bullingdon Club, to the 2007 financial crisis and austerity, the decimation of local newspapers, rising inequality, and dwindling opportunities.

The extent to which the story can be mapped through visual materials is often surprising: Margaret Thatcher’s 1975 jumper emblazoned with the flags of European countries is one of the prizes unearthed, along with the London School of Economics’ Brexit Collection, an archive of campaign leaflets from the 1975 and 2016 referendums. Though 40 years apart, the tactics of the two campaigns are remarkably consistent, and in both cases rely heavily on racism and the exploitation of fear, including the old favourite, that Britain might be “run by Brussels”.

One poster – “You are paying too much for your weekly shop” – is a frank throwback to the design trends and yellow-steeped colours of the 1970s, a pernicious tactic that activates the most powerful lever in the Brexit armoury – nostalgia. For Noni Stacey, there is no doubt that “a core element of Brexit was a looking back to a Britain that never existed.”

The fierce backlash against those, notably the National Trust, who have attempted to acknowledge and come to terms with Britain’s colonial past, is some measure of the power of nostalgia, not just to conjure comforting visions of White Cliffs and bluebirds, but to wilfully deny and even perpetuate the most egregious wrongs, in defence of a supposed status quo.

Along with the cross of St George, the blue passport, the monarchy, and green fields, the White Cliffs of Dover belong to a set of talismanic ideas and images vigorously exploited by those invested in Britain’s separation from Europe. They have proved equally serviceable by satirists, as well as more reflective explorations by artists such as the photographer Simon Roberts. Covering the years between the end of New Labour to Brexit, Roberts’s series Merrie Albion – Landscape Studies of a Small Island, chronicles the village fetes and Bank Holiday picnics that provide a collective illusion of continuity and stability in a society demoralised and bled dry by austerity.

The flimsiness of the veneer is evident in a related project, commissioned by flyingleaps, an organisation dedicated to provoking visual conversations by bringing art into public spaces. In response to the signing of Article 50 on March 28, 2017, which formally set Brexit in motion, Roberts produced a poster pairing an image of people out walking on the clifftop at Seven Sisters near Eastbourne, (white cliffs that look passably similar to the White Cliffs of Dover), with a quote from Virginia Woolf’s novel Between the Acts. Displayed in Brighton, the poster offended many residents, who saw it not as a lament for an island cut loose, but as an image of impending suicide and accidental death. In response, Roberts removed the cliff in Photoshop, confronting viewers instead with an expanse of white space.

The Englishness of Brexit is something that Stacey is especially attuned to. Currently living in Glasgow, she says there is a feeling of complete rupture from England. “I have never met anyone in Scotland who voted for Brexit”, she told me. “It’s very much seen as an English thing, which is why so many artists have looked at these facets of English identity, which I have found really, really interesting.”

The ultimate expression of this separation is in Ireland. She says “Nowhere is it clearer that Brexit is a catastrophic error, which never needed to happen.” No surprise perhaps that some of the most powerful art in her book was made around the border between Northern Ireland and the EU in the Republic. Unlike the stirring collective memories of empire and glory revived by English reminiscences, revisiting the past in these borderlands reopens a deep psychological scar, traces of which remain on the landscape.

A number of art projects have responded to the threat of a renewed hard border, and stills from Anthony Haughey’s 2019 film Blind Spot convey the utterly dispiriting bleakness of that prospect. Blind Spot catalogues the remains of the infrastructure of divided Ireland, which though decommissioned following the Good Friday Agreement, still litters the landscape. In Stacey’s book, we see broken rusting bridges, now taking on another layer of meaning.

A happy ending is not in prospect, and yet the sheer vitality of visual protest and resistance shows that, as Stacey herself puts it, “this is not over, not by a long chalk.”

Leave to Remain: A snapshot of Brexit by Noni Stacey is published by Lund Humphries, £35.