We live in a time dominated by brands and franchises. At the cinema, most films are sequels, spinoffs, or remakes; in the street, many people wear tee-shirts that function as walking billboards; and at home, children play with toy versions of their favorite characters from Frozen or Paw Patrol. In some cases, these branded objects are almost completely disconnected from the realities they are meant to recall—I know almost no one, for instance, who regularly watches Mickey Mouse cartoons, but his visage is almost inescapable.

One universally-recognized brand with global appeal is The Smurfs, the small blue creatures with friendly faces. Take a walk around any major city in the world, and, if you’re looking, you’ll find figurines of Papa Smurf or stickers depicting the Smurfs’ village. On television, there is a Smurfs show, and their fourth major theatrical film is currently in production.

Despite The Smurfs’ ubiquity, many across the world do not realize that they began life as a Belgian comic book. This is a shame, because the original comics provide a blend of imagination, humor, and whimsy that is well worth experiencing for yourself. Thankfully, for the last thirteen years, the publisher Papercutz has been releasing English translations of The Smurfs, allowing a far greater audience to enter Smurf Village as originally imaged by its creator, Pierre Culliford (better known by his pen name, Peyo). When reading Peyo’s comics, with their unique style and fun writing, it is easy to see how they spawned an empire.

Peyo’s passion

Pierre Culliford was born in 1928 to an English father and a Belgian mother. As a boy he went by Pierrot, a common nickname for Pierre. However, one of his English cousins struggled to pronounce this, instead calling him “Peyo.” Thus was born the pen name that would later be famous around the world.

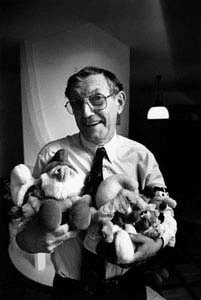

As a teenager, Peyo worked for a movie theater. Because the Nazis were then occupying his native land of Belgium, many American films were banned, and he only saw a select few movies from the United States. Two of the American movies that made their way to Peyo’s theater made a profound impression on the young man: Errol Flynn’s The Adventures of Robin Hood and Walt Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarves. Whatever their differences, the two films each pull readers into a medieval world of wonder and adventure, establishing a setting that would prove to be an enduring influence on Peyo.

The story of Peyo’s life is a good one, and for anyone interested I recommend the documentary From the World of Peyo To Planet Smurf, which the filmmakers have made available for free on YouTube.

Peyo worked as an animator for a short time, befriending fellow future comic legends Franquin (of Spirou and Fantasio) and Morris (creator of Lucky Luke). The Belgian animation studio that employed them soon folded, but Peyo never gave up on his art. He tried for years to develop a popular comic, working particularly hard on what would eventually become Johan et Pirlouit (usually translated as Johan and Peewit). With a little help from Franquin, the comic was eventually published by Dupuis. This medieval adventure comedy, about the brave page Johan and his diminutive companion Peewit, is an absolute joy. Even early Johan and Peewit stories make it clear that Peyo had a gift. The art is so precise that not a line is wasted. There is nothing extraneous, yet readers feel that they have entered a whole world.

In one story, Peyo introduced what would become his most famous contribution to the world of arts and letters: a group of small blue critters called in French “Les Schtroumpfs,” a made-up name that plays on the Dutch word for ‘gnome’ and is translated in English as The Smurfs. The Smurfs were an immediate success, with fans writing in to ask when they would appear again. Peyo had intended for the little critters to appear in just one story, The Flute with Six Holes, but he began bringing them into more Johan tales, and soon they were given their own series.

The joy of The Smurfs

The Smurfs, once encountered, are never forgotten. Like his inspiration Walt Disney, Peyo invented characters who were simultaneously simple and unique. Each Smurf is “as tall as three apples,” and had the friendly, approachable roundness of Mickey Mouse. Like the seven dwarves in Snow White, many of the Smurfs have names that fit with their easily-understood personalities. Brainy Smurf, Grouchy Smurf, Jokey Smurf, Handy Smurf, Vanity Smurf, and 94 others live in their utopian village under the kindly guidance of Papa Smurf.

The Smurfs have their own world and culture that is distinct from the medieval world that surrounds them. For instance, while their language is mostly comprehensible to humans, they use the word “Smurf” to mean almost anything. For instance, they might say, “You are smurfing an article” or “I am wearing an argyle smurf.” The Smurfs make their homes in colorful toadstools, and, despite the machinations of the evil wizard Gargamel, their adventures always have happy endings.

Biographer Neal Gabler aptly described the early work of Peyo’s hero in Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination, saying that he made “what seemed to be, oxymoronically, mass-produced folk art that appealed to everyone from sophisticated to innocents.” This is equally true of Peyo. A casual reader could be forgiven for thinking that Peyo’s work was simple, but in reality this simplicity was the fruit of laborious effort. The clearest of the ligne clar cartoonists, Peyo’s work has been compared to Charlie Chaplin films because of their steady ‘camera,’ frantic action, and easy-to-grasp plots. His friend Franquin said it best: a person could look at a page of a comic by Peyo from 15 feet away and still understand the story.

The simplicity possessed by The Smurfs is not childish, but childlike. As Peyo’s collaborator Francois Walthery put it, the Smurfs “have a very childlike vision of the world, with grass, roots, and [other small objects being part of their landscape].” They rejoice in the world that surrounds them, just as we readers are meant to do. In order to ensure that The Smurfs succeeded, Peyo would bring his assistants to forests and have them draw the wilderness from the perspective of a Smurf. He told them they had to “imitate” the Smurfs in order to draw them properly. (This approach was not just the case for The Smurfs: his old assistants delight in telling stories of having to have ‘swordfights’ with sticks, pillows, and even toy sabers in order to properly portray the action in Johan and Peewit.

What these stories emphasize is not just the fun side of Peyo’s personality, but also the incredibly high standards the writer-artist had for his work. Every page had to be perfect, which led to him (and his assistants) doing a lot of painstaking re-drawing. Peyo could never explain precisely what he objected to in a given page but instead ‘felt’ when something was off. He and his assistants would regularly begin a page from scratch after having mostly completed it.

Until Peyo’s death, the comic’s coloring was done by his wife, Nine Culliford. Readers may be unaware of what a crucial task that is, but with The Smurfs it is hard to ignore; the coloring is a key component to the series’ iconic quality. Each page is vibrant, with Smurf blue and toadstool red jumping off the paper and into the reader’s imagination. The choice to color the Smurfs blue, so momentous, was made for a simple reason. Green would have made them blend into the grass, yellow would make them look sick, and red would make them look mad … So blue it was!

The Smurfs’ designs were so immediately appealing that a cereal brand began producing Smurf figurines within a year of the comic’s first publication, for use as prizes in boxes of their products. In fact, toy versions of the characters invaded America long before, not just the comic, but the television show. In a sense, The Smurfs comic has become a victim of its own success. The characters it showcases and the world they inhabit are so iconic, so nearly archetypal, that licensed Smurfs products are attractive whether or not someone has ever read one of the comics or even seen one of the many film and television versions of the stories.

Anglophone fans of The Smurfs were generally left high and dry where the comics were concerned, instead having to content themselves with the enjoyable but far less inventive television cartoon and subsequent adaptations. While some were translated, they were not widely released or marketed, and they were far from showcasing Peyo’s complete run on the comics, let alone those that have been published since his death in 1992. The all-ages comic publisher Papercutz is thus doing readers a great favor by releasing Peyo’s comics and keeping them in print. They have released them in a number of different formats, including both single volumes and 3-in-1 volumes (in both cases, a little smaller than the original comics and slightly re-ordered), but my favorite way to read The Smurfs is in The Smurfs Anthology, of which five volumes have been released. These hardcover volumes are quite affordable and present the comics in their original size and in their original publication order. Each volume of The Smurfs Anthology has about 200 pages of comics, 50 of which are usually Johan and Peewit stories in which the little blue critters appear.

Though I have previously criticized the translations of Papercutz’ editions of Asterix as a bit wooden and less organically funny than the iconic translations by Anthea Bell and Derek Hockridge, I have no such complaints to make about the Papercutz translations of the Smurfs. Like the French originals, the Papercutz editions are easily accessible to young readers while maintaining clever wordplay to amuse older readers. Thus, these English editions retain the joy of the original French and communicate it to whole new generations of readers.

Joy is at the center of what makes The Smurfs so perennially appealing (along with the characters’ iconic designs). Some comics are remembered for being dark and gritty, and others are remembered for their intricate plots, but Peyo’s works do something different. To put it simply, reading The Smurfs is fun: it reminds us that the world is a beautiful place brimming with opportunities for adventure. It encourages us to work together towards meaningful goals and to spend time in nature. It might not be the most profound comic ever written, but it may well be the most joyful.

Peyo would always say that a cartoonist should be able to return to his work in twenty years and still be proud of it. Experiencing these comics a little over sixty years after their initial publication in a world that is, in many ways, far bleaker than the one Peyo lived in, readers are given the chance to set aside their earthly cares for a while and follow the lighthearted adventures of the blue Smurfs, in their beautiful, sylvan world.