Medicine cannot cure all diseases, but one simple yet powerful tool – art – can help patients and doctors alike, writes Dr Mogeshni Govender.

I just could not stop looking at the painting. It was large, placed in prime position behind the head of unit’s desk, such that you couldn’t not look at him, without looking at the painting.

And this was a magnificent painting, full of yellows, oranges and browns, depicting a field of some sort. I wondered where the artist got their inspiration. I went on, answering the usual job interview questions, and each time he looked down at his notes, I caught another glance at the painting. My eyes were fluctuating between him and painting. I became curious enough to suddenly ask, “That is a beautiful painting you have, who was the artist?”

He turned and looked behind him, to behold the fields depicted, so foreign it was, among the computer, his files, and the pinned-up registrar timetables and meeting lists across the walls of his office. “My wife painted it,” he replied, a subtle smile gathering on his face. “I love what she has painted, it is beautiful,” I said. We returned to the rest of the interview, with this piece of art being a wonderful interlude. As I stepped out of his office, I wondered how many others had stopped to ask him about the painting.

Art, in all its many forms, has stopped time for me, given me a creative outlet, taken me out of the protocolised hospital system, allowed me to express myself, have fun and make a mess. By art, I mean not just painting, but music, singing, writing, poetry, photography and dance.

A wise artist once told me, “Art lives on. The ruins of statues survive the test of time. We travel the world to marvel at art. But we have placed art second in schools and in life, when art holds so many valuable life lessons that cannot be gained from mainstream subjects. Such as problem solving, patience, perspective, acceptance of the imperfect, and an interpretation of oneself, each other, and our environment.”

It is well known that art is good for patients. “Health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity,” as stated by the 1947 Constitution of the World Health Organization (WHO) (here). The WHO uses art in health promotion and communication. In 2019, the WHO tested the effect of arts in advancing specific health goals, including improving mental health, suicide and blindness prevention, and maternal health (here). The WHO’s Regional Office for Europe is conducting research on the effect of art in health, in its Behavioural and Cultural Insights Program (here). Art also helps communicate health messages across different cultures and helps with emergency preparedness (here).

Art turns the stereotypical “white walls” of the hospital into a vibrant collection of colour for patients to turn to and think about, to distract time for a moment. It gives the doctor and patient a common topic to talk about when they meet walking through the hospital ward.

Painting and music are being increasingly adopted into geriatric units. I have seen how it momentarily unites patients with dementia, ignites joy, allows time to pass, and creates stimulation in an otherwise boring day as a patient on the ward. I have noticed the decrease in agitative behaviour in geriatric patients after such sessions. Music therapy is well known to assist with multiple areas in patients with Parkinson disease and other movement disorders, such as cognition, on–off period duration, motor and gait control, and mood disorder (here).

We can learn a lot from the Artful: Art and Dementia Program, conducted by the Museum of Contemporary Art (here). In this randomised control study, participants with mild to moderate dementia were exposed to a variety of artwork, textural sensory experiences were created, verbal and non-verbal responses to art were recorded, and participants were provided “art home packs” to allow them to continue exposure to art at home. The full results of the study can be found online, but visuospatial skills and memory appeared to be improved after the program. The pilot study indicated a need for further research in the area. Research has only given a miniature glimpse of the impact of art across all health dimensions.

Young patients stuck in hospital for months decline with respect to their condition as well as their mental health, due to lack of social and creative stimulation. When I have introduced the hospital’s art services to them, depression and hopelessness momentarily dissipate, and I see the young artist come to light in the patient. Outpatient eating disorder services use art to express the suffering within. Psychologists tell patients to write how they are feeling, as a means of therapy. Some of the best poetry and written work come from people reflectively writing about their lives, as it connects the human experience.

But art is also good for those who look after patients (here, here and here). Art heals the “healers” as well.

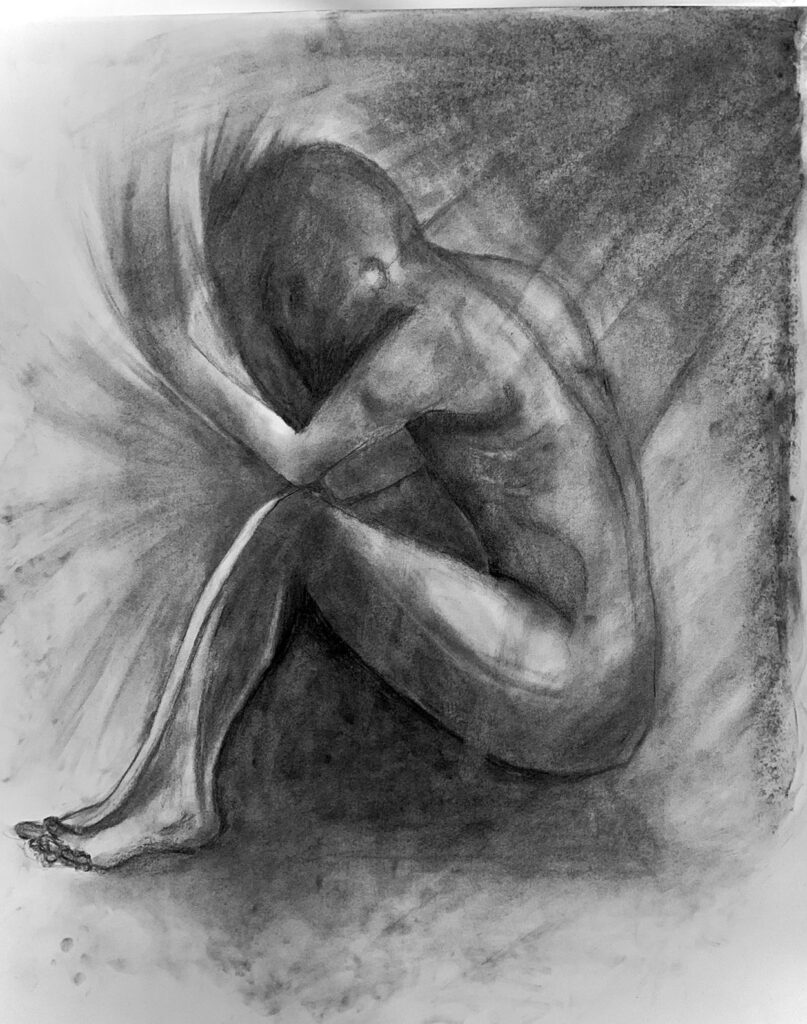

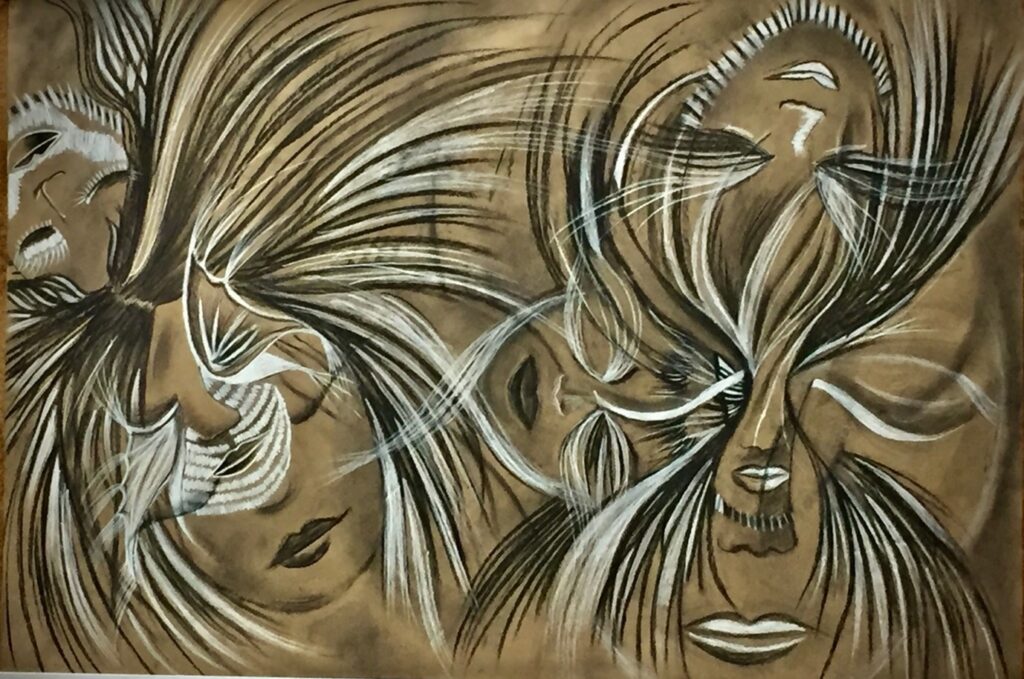

As a medical student at Flinders Medical Centre in 2018, my student friends and I spent time outside of our studies to produce pieces of work for the Flinders Medical Centre Arts in Medicine Competition for medical students and doctors. Such a competition was created to encourage and remind us of the importance of a work–life balance and the role of art, in this purpose, to promote wellbeing.

For medical students, it is vital to introduce such outlets early on, so that when we graduate and move onwards with our careers, we don’t forget to come back to art. I enjoyed the process of creating the artwork with my friends and seeing all of our work displayed on a hospital corridor wall. This wall, once blank, had come to life. The pieces from qualified doctors were the most inspiring to me, as it set an example for students to prioritise wellbeing and indicated that it is possible to make time for other pleasures outside of work. As a young doctor at the Royal Adelaide Hospital, I was captivated by the paintings for sale from local artists that lined the outpatient department corridor, as well as the photography on display from consultants and the paintings donated to the hospital.

I also reflect on hospital orchestral groups for medical students and doctors. The World Doctors Orchestra (WDO) allows doctors to “hang up the white coat” for the night and perform for charity, while raising global awareness that “healthcare is a basic human right and a precondition for human development” (here). Coming together for a common purpose helps us to remember our purpose and value as healers, allows comradery, and gives us a means to connect.

Not only has art been invaluable for aiding my wellbeing as a doctor, but the skills I have gained from art have been transferable to my work. Art has enhanced my ability to think laterally regarding clinical conundrums, with multiple perspectives. It has allowed me to “put myself in my patient’s shoes,” just as one would do when they look at a painting and try to understand what the artist is trying to convey. I can look at the fine detail of the condition and the bigger picture (the effect on the patient’s identity and social and financial life), just like I was in an art gallery looking at a piece at a distance and up close.

Indigenous artwork displayed in hospitals is one means to aid a culturally safe environment for Indigenous patients (here). It is also a reminder to non-Indigenous people in the hospital, to mentally acknowledge the Traditional Owners of the land that the hospital lies on. Engaging in art is instrumental in the wellbeing and healing of Indigenous patients. For many Indigenous people, art is not a commodity but rather as “something akin to a family member” (here). Indigenous people pass on knowledge, stories and traditions through their artwork. Many Indigenous people use art as a form of grieving as well. Therefore, engaging in and displaying art, when treating Indigenous patients, could be a valuable part of the management plan. However, it remains widely unadopted. Another example is the incorporation of Indigenous artwork into staff uniforms of the Royal Flying Doctor Service in Queensland (here), which they report has helped improve engagement of Indigenous people in their mental health programs (here).

Art as a method of healing is still viewed as an accessory tool, rather than a primary tool, in the doctor’s toolbox. This likely stems from a multitude of factors: a lack of education of doctors and medical students in the importance of art for patients and themselves, a lack of time in a busy hospital system for the doctor to remember and use available hospital art services, perhaps a feeling that art is not as important as current clinical practice backed with research, a lack of funding for art services in hospitals, and a lack of research studying the effect of art on the physical and mental health of patients. There are likely many other reasons why today, there are still hospitals in Australia without an arts service for its patients or an Arts in Medicine program for its doctors.

Medicine cannot cure all diseases. In my experience, basic skills such as simply listening have sometimes been more valuable to patients than any medications that could be offered. Art is another example of a simple yet powerful tool. One of my most memorable and rewarding times as a doctor was when a patient experiencing deep suffering and hopelessness, and for whom all treatment had been exhausted, looked up at me and smiled for the first time, after engaging in art at the bedside. They told me, “Thank you so much for getting me in touch with the art service”.

Art teaches me to try new skills, to be adventurous, to have a laugh over what I’ve created, and to not take life too seriously.

I can easily say that my favourite and most inspiring artworks will always be those produced by my “patient-artists”.

Dr Mogeshni Govender is a post graduate year 6 doctor in physician training and a medical registrar at Western Health, Victoria.

The statements or opinions expressed in this article reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official policy of the AMA, the MJA or InSight+ unless so stated.

Subscribe to the free InSight+ weekly newsletter here. It is available to all readers, not just registered medical practitioners.

If you would like to submit an article for consideration, send a Word version to mjainsight-editor@ampco.com.au.