The latter half of the eighteenth century was an era of contradictions: unparalleled luxury and abject poverty; absolute monarchs and republican pamphleteers; unquestioned faith and reasoned skepticism; Rococo fantasy and classical purity—an epoch that witnessed the splendid, waning hours of the old order and the violent birth of the modern age. For the privileged few, sculptors and decorative artists created a world of delicate gaiety that we call the Rococo: A console table by Giuseppe MariaBonzanigo; a gold snuffbox by Jean Fremin; a gilt bronze and marble mantel clock modeled by Augustin Pajou; a sécretaire by Jean Henri Riesener; and rooms from Bordeaux and Grasse all illustrate theelegance of the century’s fine arts.

In painting, the intensity of the Baroque had given way to a multitude of styles: refinement in the portraiture of Batoni, Mengs, and Gainsborough; passion and pleasure in the paintings of Fragonard; and a curious mingling of archaeology and fantasy in the works of artists like Pannini, Piranesi, and Robert. There was also a renewed fascination with the classical world—fired by the discovery of the buried cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum. Flocking to Rome as they had done for centuries, artists came to worship at the shrine of the antique, and now, on the Grand Tour, their patrons joined them—all seeking to distill from the Eternal City the transcendent truths of Europe’s classical forebears. The severe Neoclassical aesthetic found its most daring proponent in David. His Death of Socrates—austere in tone, spare of anecdote, and archaeologically and morally “correct”—provided on the eve of revolution the visual correlative of republican hopes.

As Napoleon’s army forcibly exported the ideals of the Revolution across Europe, so, too, it spread the state-supported aesthetic: The Empire style in the decorative arts and the Neoclassical style in paintingsignified as fundamental a change in the European sensibility as had the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the regicide that followed it.

The Neoclassical style initially gave artistic expression to the Revolution at its most implacable, but still-newer sensibilities were emerging that would characterize the aesthetics of the remainder of the nineteenth century: Romanticism and Realism. In England, Fuseli and Blake gave expression to the brooding Romantic spirit. In Spain, Goya refused to ignore the real and terrifying world and instead offered up a mirror of man’s capacity for brutality and compassion. In France, Ingres brought classical portraiture to its apex, while Gericault and Delacroix experimented with a brilliant palette and exotic subject matter. But it was finally in the paintings of Turner and Constable in England and Corot, Rousseau, and Courbet in France that the quintessentially nineteenth-century subject emerged: nature precisely observed on site.

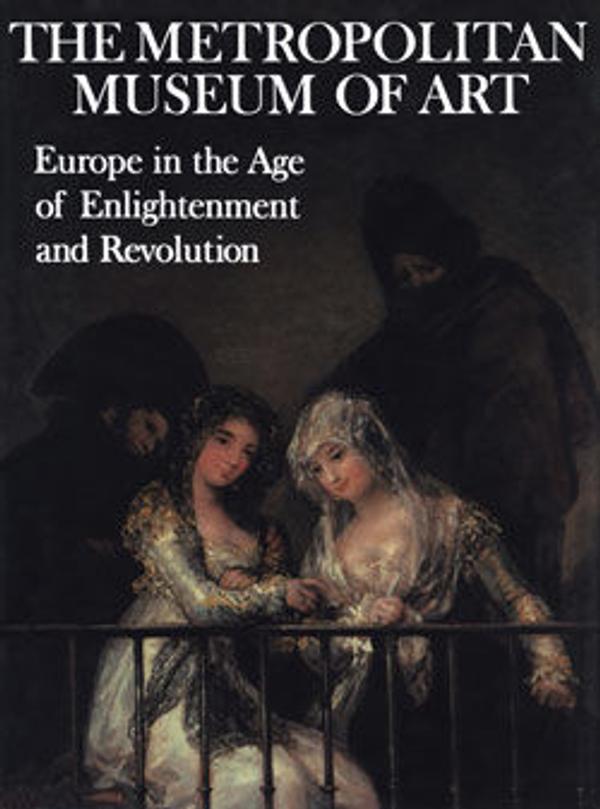

Europe in the Age of Enlightenment and Revolution presents a broad range of examples of the tastes and styles of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, all drawn from the collections of The Metropolitan Museum of Art. In all, over 120 paintings and objects are reproduced, giving a grand overview of this crucial period in European art.

Europe in the Age of Enlightenment and Revolution is one in a series of books that covers practically all of the world’s cultures, from the earliest times to the present. In total, some fifteen hundred objects, drawn from every curatorial department of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, are reproduced, most in full color.