The fighting arts of medieval Europe were long thought to be lost after the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. After all, what use did the sword and its brethren serve when wars were fought with firearms and artillery? With the aid of texts written by prominent swordsmen of the time, fencers around the world are recreating them piecemeal. Today, millions of martial artists study historical European martial arts and compete in tournaments just as knights in chivalric tales did centuries ago. So how did this development come about, and how can one learn HEMA?

The Roots of HEMA

HEMA covers a wide swathe of time and space that includes any European system of armed or unarmed fighting from the 14th through 19th centuries. During the Middle Ages and Renaissance, renowned fencers could earn money with their skills by teaching others, fighting as mercenaries, or placing themselves into a noble’s service as a soldier, bodyguard, or master-at-arms. Many of the surviving texts from which HEMA has been reconstructed come from these fencers who wanted to ensure their knowledge stayed intact or provide a guide for their students.

These martial arts systems started seeing a revival around the turn of the 20th century. Alfred Hutton, a British military officer, translated (among other treatises) the Flos Duellatorum, published in the 15th century by Fiore dei Liberi. Other fencing teachers followed in this endeavor. At first, much of the reconstruction was in rapier fencing but it later expanded to older weapons as more manuscripts were discovered and translated.

We also can’t go too far in discussing HEMA without mentioning Ewart Oakeshott. He was a historian and sword collector who wrote extensively about European swords and their uses. He also devised the Oakeshott typology, which historians use to categorize European swords from the immediate post-Roman period to the Renaissance. Oakeshott wrote several books based on what he had learned about medieval culture, weapons, armor, and history.

Recent Reconstruction

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

Sign up to our Free Weekly Newsletter

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, several organizations began to crop up in response to the growing popularity of HEMA. The Association for Renaissance Martial Arts, founded by John Clements in 1996, carried the most influence among the community at that time.

Many German longsword teachings come to us, for example, from Christian Henry Tobler, whose most well-known work is Secrets of Medieval German Swordsmanship. He reinterpreted the verse of Johannes Liechtenauer and presented the actions taken in flowchart form, which condenses the text into recognizable sequences. On the Italian side of things, we have Guy Windsor. His book The Swordsman’s Companion is considered essential reading for anyone getting started in HEMA.

However, it is the contributions of Dr Patri Pugliese that arguably did the most to aid in the reconstruction of HEMA. He would photocopy fencing treatises, bind them and physically mail them to whoever requested them, only asking for enough money to cover the cost of printing and postage.

What Weapons Are Used in HEMA?

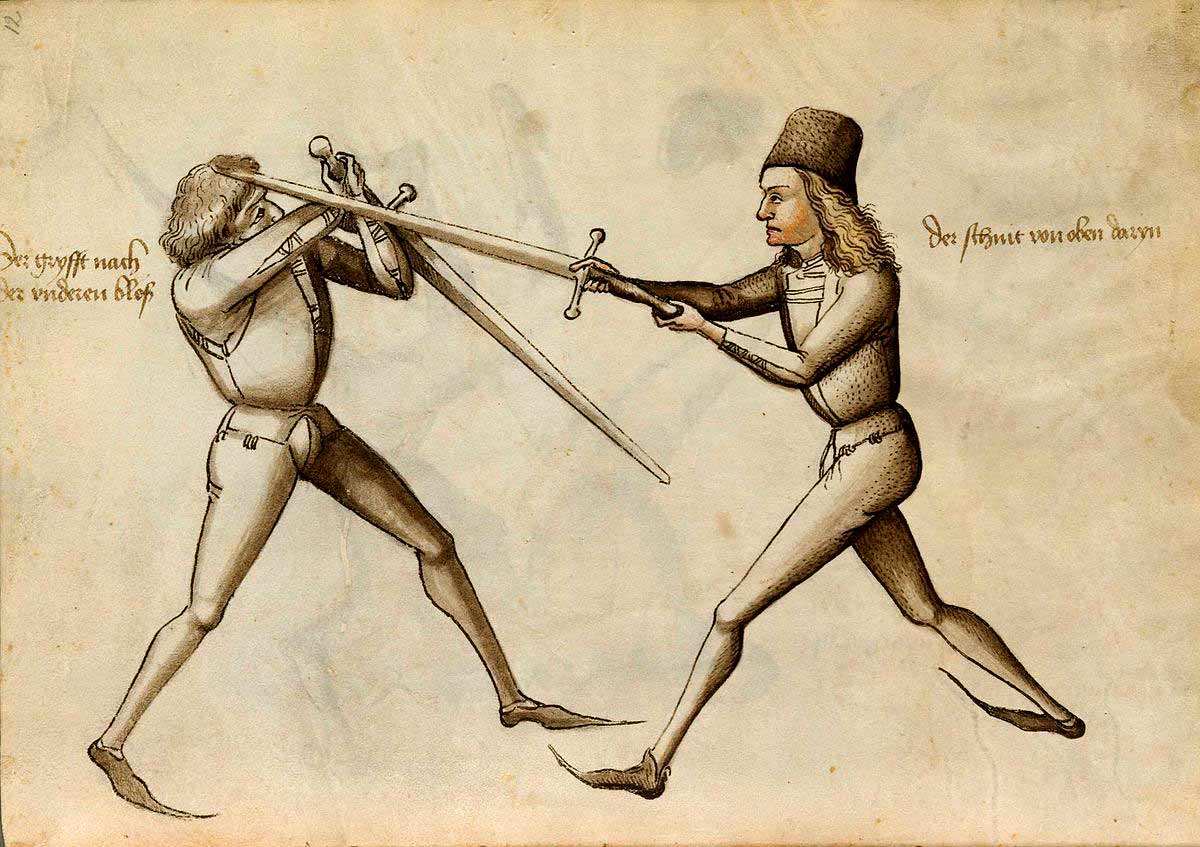

The longsword is the bread and butter for many students of historical European martial arts. It is a versatile weapon for both unarmored and armored fighting and the one for which we have the most comprehensive surviving material. It acted as a backup weapon during military engagements. Sources from Germany, Italy, and England are freely available online in the public domain.

Polearms such as the spear, halberd or axe also feature in HEMA, but only for armored fighting for both historical accuracy and safety: those types of weapons were not carried during a soldier’s day-to-day, and they are too dangerous for unarmored free sparring. The force behind them is too much for standard protective gear to withstand.

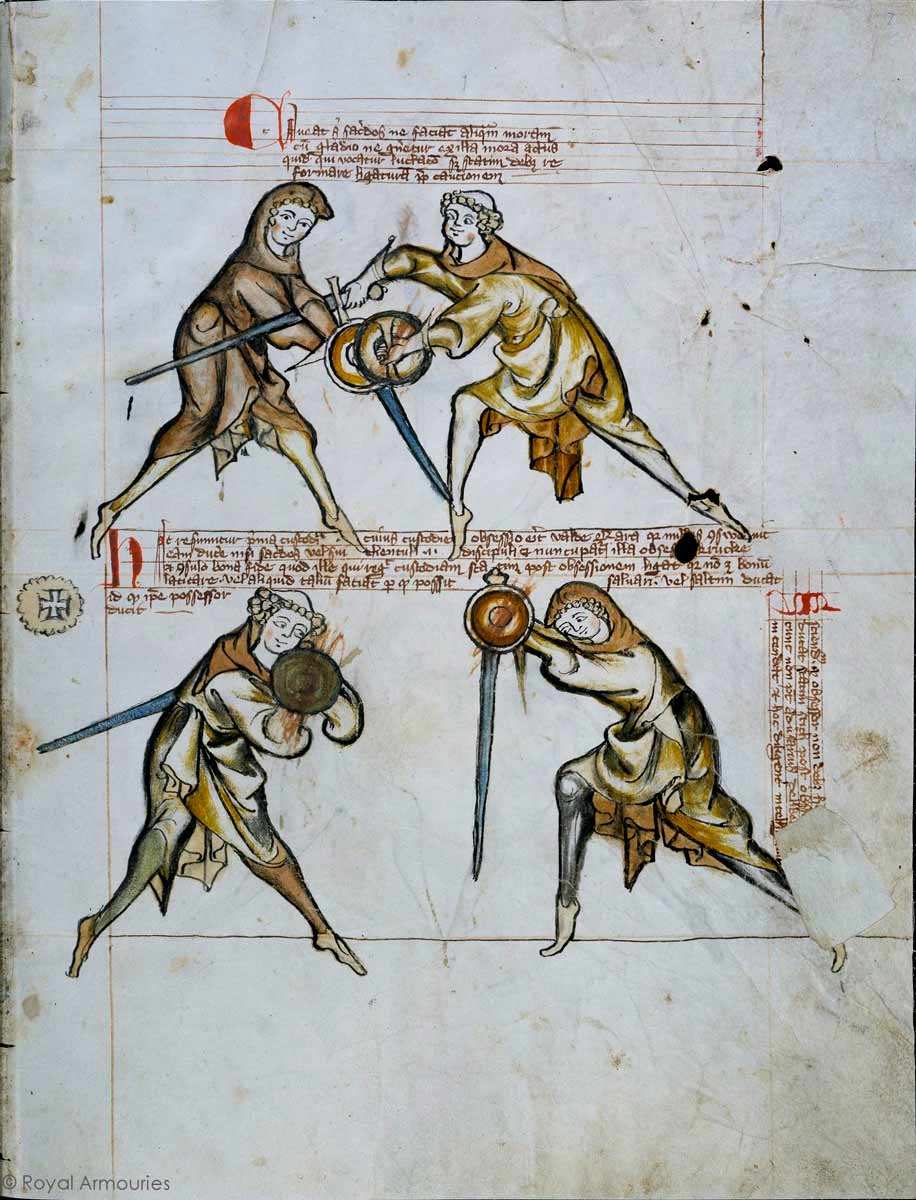

Sword and buckler, a small shield worn on the belt in civilian attire, is another system in HEMA. In fact, the Walpurgis “Sword and Buckler Manuscript” (called MSI33) is the oldest known written source, written in the 13th century. The buckler could be used with the messer, arming sword, or rapier. However, the rapier was more often paired with a dagger than a buckler.

Rounding out the HEMA weapon selection, we have the traditions of backsword and bayonet. These were used as 19th-century infantry and cavalry weapons.

Studying HEMA

HEMA students come to the art in different ways. Most will join a school in their area. Although it is growing, HEMA is still relatively niche and has gained less of a foothold compared to other martial arts. Because of this, other prospective students may meet up informally at parks or similar spaces to practice — with the approval of local authorities, given the potential risk to safety. Because this is a martial art, it can’t be learned effectively without practicing against a resisting opponent.

Reading the historical fencing manuals can also increase one’s understanding of the systems and serve as a reference guide. Because of their age, they are in the public domain and so are free to access from a variety of sites online. For example, Wiktenauer is an open wiki that hosts translations and transcriptions of dozens of manuscripts. It can be intimidating to know where to start but it depends on what weapon system one wants to study.

For students interested in learning German longsword fighting, a good place to start is the Pol Hausbuch, labeled as MS3227a. It is one of the most detailed and comprehensive longsword treatises written. For other authors, look to Hanko Dobringer, Peter von Danzig, and Hans Talhoffer to name a few. For rapier, one can read the works of Ridolfo Capoferro, Camillo Agrippa, Vincenzo Saviolo, and Achille Marozzo.

Practice Equipment

To safely practice HEMA, it is imperative that students wear protective gear. At a minimum, one needs a fencing mask and heavy gloves. The mask consists mainly of a steel wire mesh that completely encases the face and sides of the head, as well as a bib-like protrusion that provides some protection for the throat. Heavy fencing gloves consist of separated compartments for the thumb, index, and middle fingers, and the ring and pinky fingers. On top of the glove portion is a hard plastic covering that shields the back of the hand and the knuckles. This is the most common glove design; five-fingered designs exist but as of yet nothing is as safe as the clamshell glove.

Other pieces of protective equipment include a padded hood for the top and back of the head, a gorget to completely protect the throat, padded fencing jackets and pants, a plastic chest guard, a cup, and guards for the other joints like shoulders, elbows, and knees. Different sparring intensities and different weapons may allow fencers to go without some of this gear, but as mentioned, head and hand protection is vital for anyone doing partnered practice or sparring.

Practice swords can be made of wood, nylon, or steel. Most of the time, students start off with nylon because it is the safest. Once they gain control and get adequate gear, they then move up to steel for sparring and serious competition. Under no circumstances should anyone spar with wooden weapons even with protection. Wood cannot flex the way synthetic materials or even steel can.

Competitions

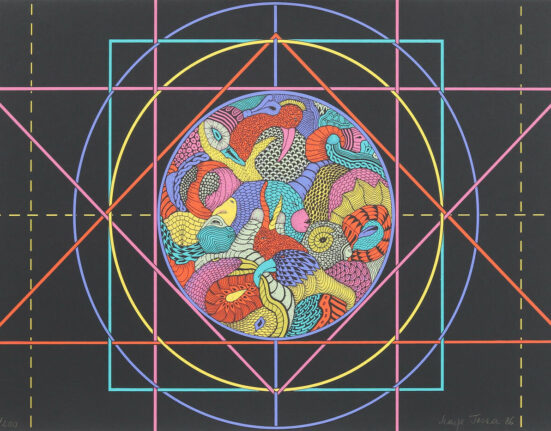

HEMA competitive tournaments originally came about as a means of pressure testing different interpretations of the manuals. The infamous debate of whether to parry with the edge or the flat, for example, had to be tested at speed with reasonable imitations of the weapons. Some of the various guards have descriptions that are difficult to visualize. Artwork gave references, but only for still postures.

Competitions also added an element of sport to the art — whether for better or worse is up to the individual to decide. Many people who study martial arts do so in order to compete with others, thereby increasing public interest, but at the same time when sportive elements are introduced it can dilute the original teachings.

Some of the most prominent HEMA competitions are Longpoint, which focuses on longsword; Swordfish, a mixed-weapons event held in Sweden and FightCamp, based out of the United Kingdom.

Scoring in competition is based on successful and decisive blows made to valid targets while keeping oneself safe. Scoring even a debilitating blow in an earnest duel would not halt the attacker’s momentum. Depending on the ruleset, afterblows can result in either both or neither fencer scoring a point. An afterblow is a hit that happens immediately after a successful attack.

Challenges in the Development of HEMA

The cost of gear can overwhelm beginner students, which is why most acquire equipment over time. Gear is made to order, which takes time and skill, and relatively few manufacturers exist yet. Because of these factors, prices are high. That being said, many students like to customize their gear with their school’s design or colors, hearkening back to knightly heraldry.

Also, the lack of a single governing body to regulate all HEMA practices for safety and accuracy can make it difficult to organize. Everyone has different priorities with regard to practice versus academic study; for the art to flourish, both aspects must be cultivated.

From the spectator side of things, HEMA when done properly doesn’t look as flashy or impressive to the layperson as something like the SCA or stage combat. Exchanges can happen in the blink of an eye and it can be difficult to see what exactly is happening or who scored a hit, even for experienced judges.

Overall, HEMA is still new in its current form and finding its place among the wider martial arts community. It has aspects for virtually everyone: serious competitors, casual fencers, those more interested in academia, and history buffs.