Charlie Squire’s enthralling book Slouching chronicles the cultural critic’s experiences of visiting museums in 23 European cities over six months

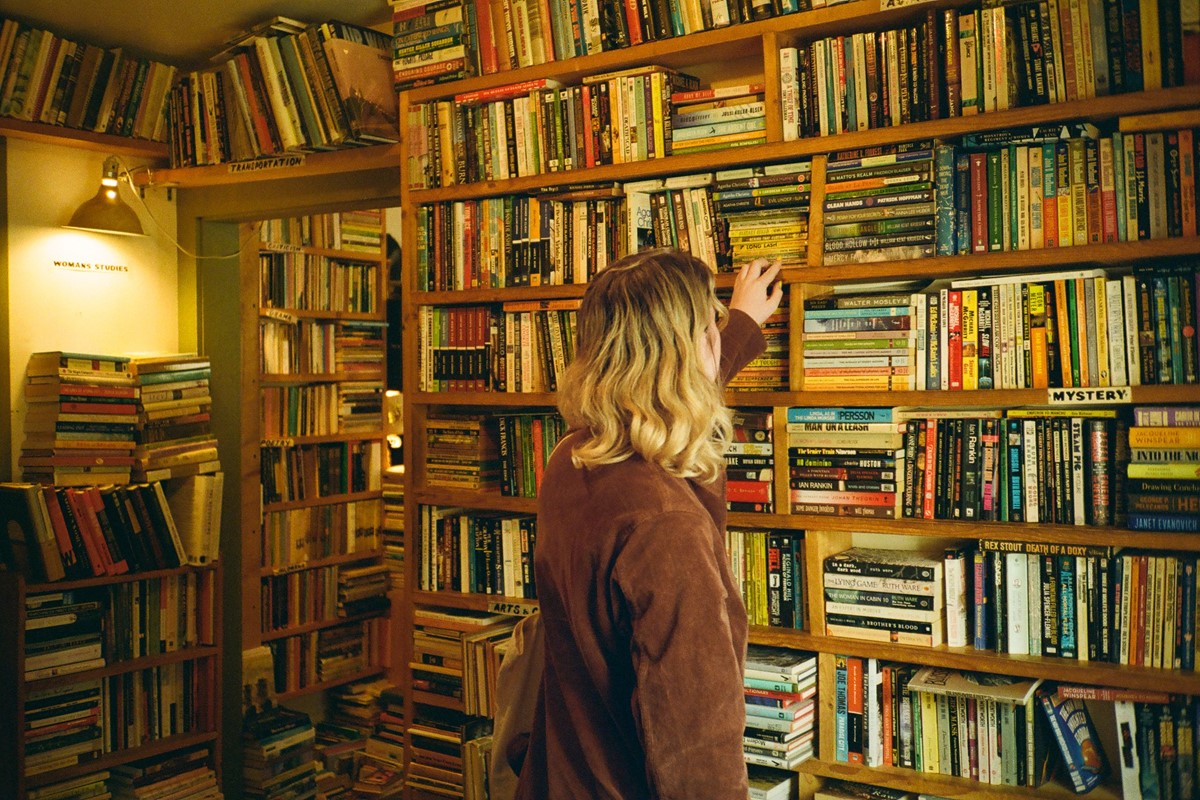

In his 1928 book One Way Street, German philosopher and cultural critic Walter Benjamin wrote about the importance of not writing but experiencing. “Keep your pen aloof from inspiration, which it will then attract with magnetic power,” he writes. “The more circumspectly you delay writing down an idea, the more maturely developed it will be on surrendering itself.” While writer and author of the uber-popular blog evil female Charlie Squire had to write down their every thought while being a Creative Impact Research Centre Europe (CIRCE) fellow this summer, their travels around Europe forced them to be uncomfortably present and still, while they explored museums and their ideological underpinnings in 14 countries and 23 cities over six months. The fellowship resulted in the publication of their book Slouching, an auto-ethnographic collection of essays about the politics of images and identities in Europe.

“Part of my writing process included reading what I considered ‘books about places’ which were set in the places I was in,” Squire tells me over Zoom. “Some of my favourites were Romance in Marseille by Claude McKay, Cutting It Short by Bohumil Hrabal, Numbers in the Dark by Italo Calvino, and, of course, One-Way Street by Walter Benjamin.”

Squire’s project examined the idea of ‘geography’ as a concept from a physical, political, and philosophical standpoint. Where do spaces begin and end? How are we shaped by the landscapes that surround us, and how do we, in turn, shape landscapes? In an era characterised by the incessant buzz of digital distractions and the relentless pursuit of productivity, it’s easy to overlook what is in front of us, but Slouching focuses on just that.

We spoke to Squire about their travels, what they learned about the political purpose of museums and the importance of creating opportunities outside of cultural institutions.

Why did you decide to focus on ‘geography’ from a physical, political, and philosophical standpoint in Slouching?

Charlie Squire: The short answer is because I thought it made a good pitch. But something that I’ve learned from school – I studied history as an undergraduate, and then I did my masters at Goldsmiths, in their critical and cultural theory programs – is how much the physical and material things around us seem to get lost to a lot of abstract postmodern ideas, and through everything being digital or intangible. The actual physical world gets lost in all that, even though all of these abstract ideas also shape them. So, I thought it was interesting to focus on being grounded while using concepts and methodologies that were so untethered.

You visited a handful of museums in the 14 countries you visited across Europe and describe them as being ‘biased sites’. Could you speak more about what you learned about the political purpose of museums in Europe?

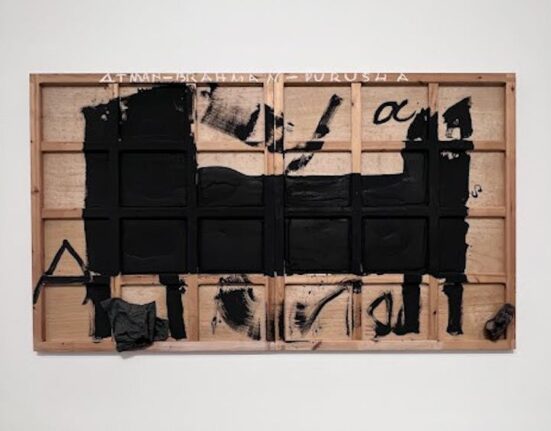

Charlie Squire: I previously worked at a contemporary art museum for a year and loved working there. I have a lot of background in art history, and I love museums and the idea of the museum as a public space. What’s so interesting to me about museums is that the practice of curation defines them, which means choosing what to put in and what to leave out. Many people have the idea that museums are neutral spaces, but the practice of curation itself is a political practice. Every choice you make is a choice that comes at the expense of one thing or in favour of another. It isn’t bad that all of these museums have some sort of narrative within them, and if you physically walk into a museum knowing that, you can interact with not only the work but also the museum itself as a text.

One of the most interesting museums I visited was the Museum of 20th Century Art in Italy. It was supposed to be one of the least political museums I saw, yet it felt very political below the surface. They were showing images by self-proclaimed fascists, and there was a lot of work by Tommaso Marinetti, who wrote the Manifesto of Futurism and the Fascist Manifesto. The museum doesn’t talk about how the paintings themselves are political and how the images are manifestations of these political ideas, which is strange because they were created from their inception to communicate those ideas and are quite obliquely propagandistic. I found it almost irresponsible because museums are supposed to be pedagogical places, and teaching people how to look is what curation is about. The Museum of 20th Century Art was not only not doing that but also obscuring what was happening.

“Many people have the idea that museums are neutral spaces, but the practice of curation itself is a political practice. Every choice you make is a choice that comes at the expense of one thing or in favour of another.” – Charlie Squire

The way you wrote about Versailles was particularly interesting to me. You start the essay stating that, ‘Versailles is full of stuff’, and end it with, ‘There is no idea of life at Versailles’. Right after I finished Slouching, I got a bunch of TikToks from people who went to Versailles, and they were all recording Marie Antoinette’s bedroom in amazement. The comment section and caption were filled with bows and other coquette-related emojis, but you weren’t impressed. Can you talk us through your experience in this heavily romanticised space?

Charlie Squire: When I was at the Immigration Museum, they pushed this narrative that nothing is more beautiful and righteous than the French Revolution. I feel like that’s so part of French identity, this belief that it is a nation born from specific ideals and not geography or regency. All that gets thrown out the window when you go to Versailles, and it’s like, ‘This is French culture: beautiful art, big hair and rituals.’ It was so strange because seeing this level of wealth is physically evocative of something uncomfortable. It reminded me of my trip to Brussels a few years ago when I saw King Leopold’s palace and there was gold everywhere. You can infer from the names if you know the history, exactly why that money is there. But you don’t see any acknowledgement of the fact that we’re looking at people’s lives and not only people in those generations, who were subjected to this colonialism but the people in generations afterwards. So, I found it incredibly frustrating that the way power and wealth operated was not only totally ignored at Versailles but celebrated.

Versallies is a fascinating building. There are a lot of interesting things to look at, and I feel like a lot of people who go there would be receptive to learning something deeper than just being able to say, ‘Oh, I wish I had that’ or ‘It must have been nice to live there’. When I walk into buildings like Versailles, all I think about is the fact so many people must have worked there. Where are the kitchens? Where are the bathrooms? Where is the labour? Versailles is emblematic of what is definitionally understood as commodity fetishism. Things within Versailles are positioned as objects that have just appeared, divorced from labour and communication and many tragic things, but also many things that are beautiful and inspiring. The flattening of the space, just so it’s entirely apolitical, does a disservice to the audience and the physical space itself as a resource. Versailles feels like you’re on a movie set. It doesn’t feel like a place where things happen. It feels like a background.

Amidst all of that, what was your favourite museum you visited and why?

Charlie Squire: The Hungarian Agricultural Museum. OMG. It’s like the coolest place in the world. It had everything that Versailles was missing; it was incredibly historically materialist. You learn about the country through the growing of crops and the changing of borders because of food and housing scarcity – all of the real things that affected most people’s lives. You get to see what ordinary people were having at dinner, how farmers were working, what technology was invented where, and how those things form Hungarian identity today, especially when the country has had so many border shifts and was once Austria-Hungary.

At the start of Slouching, you wrote that you ‘love museums – not just the archive, but the ontological complexities that they bring… Being a curator means being, above all else, a storyteller.’ Museums are complex, as your essays clearly show. Still, recently, many people have found those complications harder to grapple with as cultural institutions have been repressing, silencing and stigmatising Palestinian voices and perspectives. How do you think we can reckon with our love for museums and what they can do with what they choose to do?

Charlie Squire: One of the most difficult parts about taking on this project for me was taking money from the German government and the Council of Europe. I had a hard time with the fact that this beautiful, wonderful thing that is public arts funding in Europe is basically a project in soft power. I could write as much as I wanted saying, ‘I hate Germany, and I hate the EU’, which are things I only feel sometimes. That in and of itself would support this thesis that Europe is this paradise of free speech and expression. I think that many people working in museums also feel that no matter what you do, you are serving some political or national agenda. I think there is a certain degree of how far museums can be radical and that they can do really, really wonderful things. The fact that they have this sort of inherent limitation isn’t necessarily the fault of the curators and the staffers but also underscores the importance of walking into those spaces with a critical eye and then creating opportunities outside of them.

“Passion, desire, boredom and all of these just very base feelings are the things that create culture, and their fingerprints are on everything around you” – Charlie Squire

What has this project taught you about yourself?

Charlie Squire: I write about this at the beginning of the book, on the first introduction page, which is that it wasn’t like a coming-of-age project. I felt more or less like the same person, and that in and of itself was pretty difficult, you know? I Eat Pray Love’d and now I’m back in my apartment.

It reminded me how much I love and am always interested in everything. I think the most valuable thing I learned was how to talk to strangers, how wonderful it is, how interesting everyone is, and how you have something in common with everyone. That might be cheesy, but it’s also very true. It also reminded me that there is something beautiful about pursuing pleasure, slowness, and idleness. I learned so much and felt so challenged by moments while sitting at a table with my friend, walking down the street, or on the train. There’s this quote by Publius Terentius Afer, the ancient Roman playwright that translates to ‘Nothing human is alien to me’. Passion, desire, boredom and all of these just very base feelings are the things that create culture, and their fingerprints are on everything around you. Finding the interest, the desire and the inspiration behind very mundane things is so fascinating. I feel like not only do you learn so much about the world, but you learn so much about yourself.

Boredom is so incredibly important.

Charlie Squire: Everyone should have be forced to be bored, sometimes.

Slouching is self-published by Charlie and is available for order here.