There has been plenty of talk that the trade for pre-21st century art has now become a “masterpiece” market. The super-wealthy have become so rich that they only want to buy the best of the best by the biggest legacy names.

Further down the price scale, if business for lesser works by long-established or long-dead artists is slow, huge one-off results for purported masterpieces reinforce wider perceptions that the market is booming and art is a profitable investment. At least, that is the hope.

But a closer look at the recent supply of “masterpieces” raises the questions of how many are truly the best of an artist’s career, instead of merely the best of what is available—as well as what “the best” even means now.

After May’s underpowered series of marquee modern and contemporary auctions in New York—ArtTactic, the art market analysis firm, calculates sales were down 42% by value compared with the equivalent auctions in 2022—many in the trade were relieved when Sotheby’s announced it expects to raise at least $400m from its November 8-9 sales of 20th-century art owned by the collector and patron Emily Fisher Landau. The two-part auction of around 120 works is led by a 1932 Picasso “masterpiece” guaranteed to sell for more than $120m.

A generous supporter of New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art, Fisher Landau, the widow of a New York property developer, died in March, aged 102. Despite being denuded by a gift of 367 works to the Whitney in 2010, her collection is “era-defining” and still contains “key masterpiece examples” by American post-war artists such as Jasper Johns, Willem de Kooning, Robert Rauschenberg, Mark Rothko, Ed Ruscha and Andy Warhol, according to Sotheby’s. The house even puts her “unparalleled” holdings on a par with the “great pioneer collectors of the 20th century”, like Peggy Guggenheim and Gertrude Stein.

Given how important prestigious single-owner collections are to an international auction house’s sales figures (if not always its bottom line), Sotheby’s can be forgiven a little hyperbole. Last November its arch-rival Christie’s sold what it described as the “incomparable” collection of Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen for $1.6bn, the most ever achieved for a single-owner collection at auction. If one cannot compete on price, one must at least compete with compelling language.

The art market increasingly tends to differentiate major private collections mainly in terms of how much money they are worth. But comparing Fisher Landau with one of the autumn’s other big-name auction consignments shows how much the psychology of collecting has changed over the years.

Rothschild’s residue

Christie’s, which has also been free and easy with the M-word, held its Rothschild Masterpieces auction series in New York from 3-17 October. In reality, these four sales represented the residue of the once-great private collections of fine art and objects amassed—and sold—by this famous European banking family since the 18th century. The Rothschild dispersals culminated in 1977 in Sotheby’s legendary nine-day sale of the contents of Mentmore Towers in Buckinghamshire, which raised a then-astounding $10.3m from works by Thomas Gainsborough, Joshua Reynolds and François Boucher, among other canonical figures.

Nearly half a century later in New York, this latest series of Rothschild auctions was led by a 17th-century Gerrit Dou painting of a young woman standing in a window holding a dead hare, sold for $7.1m against a $3m-$5m estimate. Dou was a talented artist, but is that genre picture really the stuff of “masterpieces” like Rembrandt’s 1634 marriage portraits of Marten Soolmans and Oopjen Coppit, which the Rothschilds sold privately for €160m to the Rijksmuseum and the Louvre in 2015?

James Stourton, the author of the 2007 book Great Collectors of Our Time: Art Collecting Since 1945, makes a clear distinction between the thinking behind historic collections, like those amassed by the Rothschilds, and collectors of our own era.

“The difference today is that collectors buy art to show it—it is not about domesticity, and this is reflected in the art itself,” says Stourton, a former UK chairman of Sotheby’s. “What [Charles] Saatchi, [Eli] Broad, [François] Pinault, Dakis Joannou etcetera are doing is certainly collecting, but also to stage revolving shows in their kunsthalle, rather than furnish their homes.”

Like the contemporary mega-collectors Stourton mentions, Fisher Landau established a private museum where she showed selections from her holdings, at that time numbering around 1,200 pieces, to the public. The Fisher Landau Center for Art occupied a disused factory in Long Island City from 1991 to 2017. As well as having tax benefits, private museums can confer an aura of curatorial validity—even masterpiece quality—on exhibited pieces that even the most opulent 19th-century domestic interiors could not.

But does the Fisher Landau auction tell, as Sotheby’s states, “the entire story of 20th-century art in all its ground-breaking chapters” as powerfully as a private museum like, say, the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice?

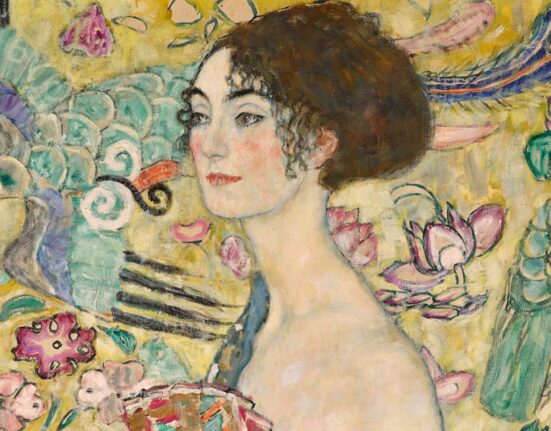

The key talking point is of course Fisher Landau’s 1932 Picasso, particularly as 2023 marks the 50th anniversary of the artist’s death. Purchased in 1968, when the 40-something Fisher Landau first started collecting, Femme à la Montre (woman with watch) comes from the celebrated series of pictures inspired by the middle-aged Picasso’s adulterous love affair with Marie-Thérèse Walter.

“He has painted and drawn no other woman in the same way, and no other woman half as many times,” wrote the critic John Berger in his classic 1965 study Success and Failure of Picasso. “What makes these paintings different is the degree of their direct sexuality.”

But Femme à la Montre lacks the languorous sensuality that characterises the market’s most coveted 1932 Marie-Thérèse paintings, such as Le Rêve (the dream), reportedly bought by the New York collector Steven A. Cohen from the Las Vegas casino owner Steve Wynn for $155m in 2013. That work has achieved consensus among critics and the market as one of the most “successful” paintings in the series, even a masterwork. Femme à la Montre, apparently, has not.

Picasso was a major thief of his fellow artists’ discoveries. [Femme à la Montre] looks as if he were trying to bring together Matisse and Léger, and somehow overdid himself

Christian Ogier, Picasso specialist

“It is big, it is colourful, and it is 1932, but it looks stiff and stereotyped,” says Christian Ogier, a Paris-based dealer who specialises in Picasso. “Picasso was a major thief of his fellow artists’ discoveries. Here, it looks as if he were trying to bring together Matisse and Léger, and somehow overdid himself.”

Tick-tock appeal

Yet Femme à la Montre has other, novel virtues, according to Sotheby’s, being one of only three major works by the artist to feature a watch. “Picasso had a deep passion for exceptional timepieces, and in fact owned three of the greatest watches in existence. To depict his young lover wearing one of his treasured watches was therefore to bestow on her the greatest of honours,” says Sotheby’s.

Fine watches have become a central component of international auction houses’ luxury offerings: Sotheby’s, Christie’s and Phillips combined sold $562m worth of watches (after fees) in 2021. The markets for fine art and luxury continue to align, turning the presence of a wristwatch into a key selling point for a $120m Picasso.

“‘Masterpiece’ is not a defined term. It’s malleable,” says Doug Woodham, a former Christie’s executive turned managing partner of the New York-based firm Art Fiduciary Advisors, as well as the author of the book Art Collecting Today.

When experts use the M-word, “they typically consider how the piece fits into the artist’s broader oeuvre”, adds Woodham. “The bar for A+ works is extremely high. However, for many buyers, this rigorous criterion may not be their guiding definition. The value of the word, unfortunately, has been diluted by overuse.”

During the same week that Sotheby’s is to auction the Fisher Landau collection in New York, Christie’s plans to offer “that rarest thing: a masterpiece rediscovered” in the form of a long-unseen Monet Le Bassin aux Nymphéas (water lily pond) painting, estimated to raise at least $65m. Held in the same family collection for the past 50 years, this is one of 14 or so large-scale canvases, each measuring two metres wide, that Monet executed at Giverny around 1917-19. These were precursors to his final magisterial, panoramic 1926 water lily grandes décorations, now at the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris.

Back in 2008, Christie’s sold another painting from this two-metre Le Bassin aux Nymphéas series in London for $80.4m, then an auction record for Monet. That example appeared to be fully finished and bore a painted signature, while this latest canvas is more loosely worked andhas a stencilled signature.

There is general agreement that the Musée de l’Orangerie water lily décorations are the culminating masterpieces of Monet’s career. But are those two-metre forerunners masterpieces too?

Nowadays, when it comes to such aesthetic judgments, what defines our era is the way that the market makes those decisions.