Public art is nearly as old as human civilization itself, with countless monuments and statues erected over the eons. Though today public art is generally associated with temporary outdoor installations, New York City does have its fair share of permanently fixed alfresco artworks, including many modernist and contemporary examples dating from the mid-20th century onward. If you want track down some of the most important of them, consult our list below.

-

Tony Rosenthal, Alamo (1967)

Image Credit: Deb Cohn-Orbach/UCG/Universal Images Group via Getty Images. The city’s most recognizable outdoor sculpture, Alamo, better known as the Astor Place Cube, has sat across from the Cooper Union building at 41 Cooper Square for more than 55 years. Balanced on one of its vertices, Alamo was originally meant to be temporary, but East Village residents successfully petitioned to make it permanent when it became a neighborhood favorite, thanks in part to the fact that it could be spun around an interior pole—admittedly with some effort, since it measures 15 by 15 by 15 feet and weighs nearly a ton. It was never meant to be interactive; artist Tony Rosenthal intended to rotate it into position and then lock it down, which he never did. Made of Cor-Ten steel painted black, Alamo is indented with geometrical motifs, including an arch that reminded Rosenthal’s wife of the door to the namesake mission building in Texas. The Astor Place Cube was removed twice for maintenance, once in 2005 and again in 2016.

-

Isamu Noguchi, Red Cube (1968)

Image Credit: CBS via Getty Images. Like Alamo, this Financial District landmark in front of 140 Broadway is a giant cube (roughly speaking) set on one corner, though the two works immediately diverge from there. For one thing, Noguchi’s sculpture is an elongated rhomboid stretched vertically to echo the height of the surrounding towers that make up Lower Manhattan’s architectural canyons. For another, Red Cube is cut through by a cylindrical aperture along one of its axes, creating a kind of viewfinder leading the eye to the high-rise behind it. The sculpture’s bright-red finish and dynamic configuration make for an eye-popping contrast with that building’s gridded glass façade. In a nod to the frenetic, casino-like atmosphere of the New York Stock Exchange and the risky nature of high-stakes investment, Noguchi described Red Cube as a rolling die.

-

Jean Dubuffet, Group of Four Trees (1969–1972)

Image Credit: Eye Ubiquitous/Universal Images Group via Getty Images. Another Wall Street area monument, Group of Four Trees is in the public plaza outside the former home of Chase Bank at 28 Liberty Street. It’s the creation of the noted French artist who coined the term Art Brut in the late 1940s. Dubuffet was referring to creations by self-taught individuals, often institutionalized, whose visionary expressions greatly influenced his own work—including Four Trees, a ghostly copse of crude arboreal forms, interlocking white shapes outlined in black like a 3D cartoon. Commissioned by Chase’s former chairman David Rockefeller in 1969–72, Four Trees is made with fiberglass, resin, and polyurethane paint supported by an aluminum and steel armature. Measuring 38 by 40 by 34 feet and weighing 25 tons, it was the largest public artwork at the time of its unveiling in 1972; it continues to stand today as an embodiment of mid-century corporate largesse.

-

Charles Ray, Adam and Eve (2023)

Image Credit: Brookfield Properties. Among the newest of New York’s permanent public sculptures, Adam and Eveis situated within the freshly completed Manhattan West development (385 Ninth Avenue) that rises just across Tenth Avenue from Hudson Yards. The piece depicts the original sinners of the Bible as an aged couple undaunted by the mess they created for the rest of us. They’re the handiwork of West Coast artist Ray Charles, whose signature approach to figuration takes a detour through the uncanny valley. The larger-than-life Adam and Eve follows suit with realistic details—including Adam’s paunch—undermined by the shiny surface of the solid-aluminum blocks from which the figures were machined. Charles renders them as a pair of geriatric hipsters, most likely artists, with Adam sporting a Benjamin Franklin fringe of shoulder-length hair and Eve, who is seated, wearing an insouciantly tied scarf, as if they’d wandered into a gallery opening after their banishment from the Garden of Eden.

-

Louise Nevelson, Shadows and Flags (1977)

Image Credit: Bill Wassman/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images. Regarded as the “grande dame of contemporary sculpture,” Louise Nevelson was a rare instance of a woman artist who succeeded within New York’s male-dominated postwar art scene—and she did so in a medium notable for its macho ethos. Nevelson’s best-known works comprise monumental, cabinet-like structures containing abstract objects; this outdoor grouping created from salvaged scrap metal and old machine parts represents her approach to sculpture in the round. Painted black, the sculptures are built around columns measuring 20 to 40 feet high, each supporting numerous curved forms meant to evoke banners flapping in the breeze. Installed in 1977 in the Financial District’s Legion Memorial Square (10 Liberty Street), the project was dedicated the following year with the site renamed Louise Nevelson Plaza, the first such honor given to an artist in New York. There are six sculptures today; a seventh was hit by a truck and permanently removed in 2007.

-

Frank Stella, Jasper’s Split Star (2017)

Image Credit: Beata Zawrzel/NurPhoto via Getty Images. Installed in 2021, this sculpture by Frank Stella stands in the fountain at 7 World Trade Center formerly occupied by Jeff Koon’s Balloon Flower. It’s a humongous 12-pointed star bulging as if ripped on steroids. Half of the piece, patinated a silver-gray, appears solid, while the other half is a schematic lattice with brightly colored elements. Jasper’s Split Star is a sculptural reprise of an earlier Stella painting, Jasper’s Dilemma (1962), a diptych of concentrically banded squares, one highly chromatic, the other in grisaille. Separated by 55 years, both works are homages to Jasper Johns, inspired by his quote “The more I work with color, the more I start to see gray.” Split Star marks Stella’s return to Ground Zero: Two of his paintings hanging in the lobby of the original 7 World Trade Center were destroyed along with the building on 9/11.

-

Joseph Beuys, 7000 Oaks (1982–2021)

Image Credit: Johannes Schmitt-Tegge/picture alliance via Getty Images. Positioned at regular intervals down West 22nd Street between 10th and 11th Avenues, this outdoor installation by legendary German artist Joseph Beuys consists of a series of trees of differing varieties (Bradford Callery pear, common hackberry, ginkgo, Japanese pagoda, Japanese zelkova, littleleaf linden, pin oak, sycamore, and thornless honeylocust) coupled with rough-hewn columns of basalt rock measuring four feet high. Sponsored by the Dia Art Foundation, the project originally started with the planting of 7,000 such pairings throughout Kassel, Germany, for the 1982 edition of Documenta taking place there. Beuys had always intended to continue installing versions of the piece throughout the world as part of a global initiative to spark environmental and social change, but his death in 1986 derailed those ambitions. Two years later, however, Dia installed five tree/rock pairs outside its building at 548 West 22nd Street, with another 33 added by 2021.

-

Mark di Suvero, Joie de Vivre (1998)

Image Credit: Werner Bayer. Joie de Vivre is an abstract configuration of two tripods vertically joined tip to tip, Its title, bright-red palette, and vague suggestion of a figure with its arms thrown in the air make this monument seem like a celebration of life. Rising 70 feet, the sculpture soars above its site at Zuccotti Park in the Financial District. Previously situated in St. John’s Park near the Holland Tunnel rotary, the piece was moved to its current location at the intersection of Broadway and Cedar Streets in June 2006. Zuccotti Park, of course, later became famous as the locus of 2011’s Occupy Wall Street movement, which was sparked by the Federal government’s bailout of banks responsible for the 2007–08 financial crisis. Joie de Vivre itself became embroiled in the protests when a man climbed up the structure and remained there for several hours before police forced him down.

-

Keith Haring, Figure Balancing on Dog (1989)

Image Credit: Richard Levine/Corbis via Getty Images. Permanent public artworks by Keith Haring can be found all around NYC, but most of them are murals, the best-known of which is Crack Is Wack, painted in 1986 on both sides of a handball court wall in Harlem in response to the 1980s crack-cocaine epidemic. In terms of freestanding sculptures, however, there’s only this single example in front of 17 State Street, across from Battery Park. Painted fire-engine red, Figure Balancing on Dog is fabricated out of interlocking steel plates, bringing Haring’s signature cartoonish outlines to three-dimensional life. Redolent with Haring’s usual whimsical brio, the piece is located at the eastern corner of the address, next to the Shrine of Saint Elizabeth Anne Sexton. It was joined by another Haring piece, Two Dancing Figures, at the opposite end of the building until the latter’s removal in March 2018 to make way for a corporate logo.

-

Anish Kapoor, untitled (2022–23)

Image Credit: Michael M. Santiago/Getty Images. This legume-shaped, yet-to-be-titled sculpture by Anish Kapoor has been nicknamed the NYC Bean, or Mini-Bean, thanks to its obvious resemblance to Kapoor’s Cloud Gate (2006) in Chicago’s Millennium Park, dubbed the Bean. The latter, however, is an expression of civic pride, while the New York version is high-cultural amenity for a luxury condo development at 56 Leonard Street in Tribeca. Colloquially called the Jenga Tower, the high-rise, designed by the Swiss “starchitecture” firm of Herzog & de Meuron, came with the unique selling point of having its own public artwork as part of its structure—quite literally, as the piece appears to be squashed under a setback over the building’s entrance. Though 56 Leonard opened in 2017, the sculpture itself wasn’t fully installed until 2023, becoming an immediate Instagram hit thanks to the bulbous contours and mirrored surface it shares with its big brother in the Windy City.

-

Xavier Veilhan, Jean-Marc (2012)

Image Credit: John Wisniewski. The name behind this enigmatic figure on the northeast corner of 53rd Street and Sixth Avenue isn’t a familiar one in New York, though Xavier Veilhan has a considerable reputation in his native France. Veilhan’s style might be described as neo-modern minimalism, with subjects often rendered in prismatic planes that make an obvious nod to Cubism. Such is the case with this full-length, larger-than-life portrait of Veilhan’s friend and fellow French artist Jean-Marc Bustamante. Painted a deep shade of cerulean that recalls Yves Klein’s emblematic International Klein Blue, Jean-Marc was created through Veilhan’s usual practice of scanning an object with 3D technology before milling it out of industrial polyurethane, aluminum, or, as here, stainless steel. Though Veilhan has created numerous public sculptures throughout Europe and Asia, Jean-Marc, which stands at 1330 Sixth Avenue, just down the street from the Museum of Modern Art, represents his first in New York City.

-

Joan Miro, Oiseau Lunaire (Moon Bird) (1946–49; enlarged 1966)

Image Credit: John Lamparski/Getty Images. A giant of 20th-century art closely associated with the Surrealist movement (though he was never officially a member), Joan Miro used abstracted forms to evoke dreamlike imagery. Moon Bird, a 14-foot-high bronze in front of the 58th Street side of the Solow Building (9 West 57th Street), is a prime example. Miro described this stocky, Pikachu-like creature as a kind of lunar deity, and accordingly, its torso, head, arms, and legs are shaped as a series of connected crescent shapes. Originally created in the late 1940s in a much smaller version, the figure was enlarged in the mid ’60s, and several were cast in bronze, including this one. Moon Bird was moved to its current location in 1994 after the building’s developer, Sheldon H. Solow, determined that an Alexander Calder mobile commanding the spot had become a hazard to pedestrians during high winds.

-

Hank Willis Thomas, Unity (2019)

Image Credit: Christina Horsten/picture alliance via Getty Images. Since 2019, this 22.5-foot-high bronze of a vertically upraised arm culminating in an extended forefinger pointed skyward has been holding forth at the intersection of Tillary and Adams Streets, welcoming motorists entering the Borough of Kings from the Brooklyn Bridge. As the title suggests, the sculpture celebrates the multifaceted character of Brooklyn and its widely diverse cast of neighborhoods, ethnicities, and races, working together to make it the most vibrant of the five boroughs. “It is intended,” artist Hank Willis Thomas once said, “to convey . . . ideas about individuals and collective identity, ambition, and perseverance.” Thomas has spent two decades exploring issue of identity and how it is expressed through the body politic. He is no stranger to public sculpture, having produced, for example, All Power to All People, a giant Afro comb stuck in the ground that has been exhibited in Philadelphia and Harlem, as well as at Burning Man.

-

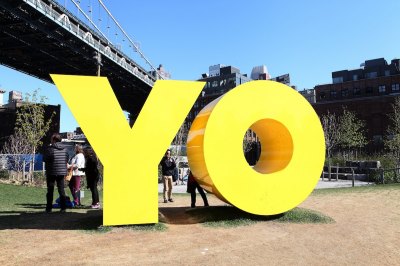

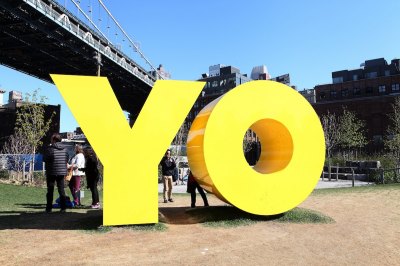

Barbara Kass, OY/YO (2015)

Image Credit: Raymond Boyd/Getty Images. Like Hank Willis Thomas’s piece, Barbara Kass’s OY/YO could be construed as a paean to Brooklyn, or perhaps to anywhere in New York City where both words are routinely uttered—in other words, everywhere. Measuring 8 by 17 by 5 feet and painted in bright safety yellow, the sculpture comprises a capital O and Y in extra-bold, sans-serif letters. Essentially it’s a monumental palindrome reading from one side as “oy” and from the reverse as “yo.” The former factored into the origin of the idea in 2011 when Kass painted the word in the same color and font as the titular onomatopoeia appearing in Ed Ruscha’s OOF from 1962. Kass added “yo” in later renditions, including a two-sided billboard project. The sculpture was first installed as a temporary project in Brooklyn Bridge Park before it was acquired by the Brooklyn Museum (200 Eastern Parkway), where it sits in front of the entrance.

-

Henry Moore, Reclining Figure (1963–65)

Image Credit: Robert Nickelsberg/Getty Images. Opened in 1967, Lincoln Center is a gleaming marvel of mid-century architecture, albeit one built on the razing of a racially mixed, working-class neighborhood called San Juan Hill—an original sin that arguably calls for a public memorial. In the meantime, this monumental bronze by British artist Henry Moore echoes the modernist ideology embodied by its surroundings. Set in the reflecting pool of Lincoln Center Plaza, the sculpture depicts separated halves of a female figure rising from the water with head and torso on one side and legs on the other. Moore likened the size of the pool to that of a cricket field, and while his piece is suitably large, it was based on an existing design rather than something new. Lincoln Center had to negotiate with Moore to make sure its commission wouldn’t be upstaged by others proposed for sites around the city.

-

Isa Genzken, Rose III (2018)

Image Credit: Christina Horsten/picture alliance via Getty Images. Standing 26 feet high and weighing 1,000 pounds, German artist Isa Genzken’s painted steel Rose III was planted at the northwest corner of Zuccotti Park in September 2018, during the seventh anniversary of Occupy Wall Street’s takeover of the park. Whether the timing was intentional remains unknown, though Brookfield Properties, which commissioned the piece, owns Zuccotti Park and probably wasn’t happy with the events of 2011. Based on a yellow rose the artist picked in Switzerland, the piece is, as the title suggests, the third iteration of the sculpture. The first, from 2003, is permanently installed in Tokyo’s Roppongi Hills development complex; the second is now in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art after debuting as a façade installation at the New Museum in 2010, remaining there for three years.

-

Santiago Calatrava, The New York Times Capsule (1999–2001)

Image Credit: NYC Department of Parks and Recreation. Fans of Looney Tunes cartoons may remember the one about a construction worker demolishing an old building who discovers a time capsule with a frog inside. It jumps out and immediately starts singing and dancing, and the man, dollar signs in his eyes, rushes off to cash in on his remarkable find. After renting a theater to present the animal, the frog refuses to perform for audiences, and the man finds himself driven to madness and penury. Designed by Oculus starchitect Santiago Calatrava, the ornately futuristic, five-foot diameter, stainless-steel New York Times Capsule has been sitting on the grounds of the American Museum of Natural History (200 Central Park West) since 2001, and sadly, there’s no immortal amphibian among the 100 or so 20th-century artifacts welded inside. In any case, who knows whether humanity will be around when it’s scheduled to be opened in the year 3000?

-

Fritz Koenig, The Sphere (1968–1971)

Image Credit: Mario Tama/Getty Images. Battered and caved in, German artist’s Fritz Koenig’s The Sphere is noted for being a survivor of 9/11. Measuring 17 feet tall and 25 feet in diameter, the abstract bronze globe stood in the World Trade Center’s plaza from its dedication in 1971 to the 2001 attacks that brought the Twin Towers crashing down around it. Miraculously, the sculpture was left mostly intact, becoming a memorial to the tragedy as well as a symbol of the city’s recovery from it. After 9/11, The Sphere was temporarily disassembled and moved to a hangar at JFK Airport along with other remnants of the World Trade Center. Left in its damaged condition, it was put on view at Battery Park between 2002 and 2017, then moved to its current location at Liberty Park (155 Cedar Street) overlooking the September 11 Memorial and its original site. In 2001 it became the subject of a documentary titled Koenig’s Sphere.

-

Kristin Jones and Andrew Ginzel, Metronome (1999)

Image Credit: UCG/Universal Images Group via Getty Images. Completed in 1999, Metronome is a monument to time and its philosophical import. Commissioned by developers the Related Companies, the piece is installed on the facade of a building facing Union Square (1 Union Square South) and consists of several components that include a massive rock and a hand from an equestrian statue of George Washington. The two largest elements are a large LED clock displaying hours, minutes, seconds, and percentages thereof in military time; and a huge sculptural relief in partially gold-leafed brick of concentric circles radiating outward from an aperture that at one point issued a plume of steam—at noon and midnight—until it stopped working. That wasn’t the only glitch, as the digital clock itself displayed the wrong time for more than a year in 2010–11. Metronome is arguably the least liked outdoor sculpture in NYC, having received numerous public complaints as well critical derision from the New York Times and other papers.

In 2020, Metronome’s clock was adapted by artists Andrew Boyd and Gan Golan to show the years, days, and hours that humanity has remaining to take action on climate change.

-

Mary Miss, South Cove (1984-87)

Image Credit: Battery Park City Authority. Like the rest of Battery Park City, Mary Miss’s South Cove is built on landfill left from the original World Trade Center’s construction in the early 1970s and is consistent with the Land Art aesthetics of that time. Miss followed the genre’s playbook by creating Cove as a site-specific amalgam of pier, contemplative green space, and scenic overlook. In short, South Cove is a waterfront park defined by epistemological references to its social and geographical context, with blue ship’s lanterns, for example, hung along an esplanade to evoke the city’s maritime heritage, and an elevated viewing platform that echoes the shape of the crown atop the Statue of Liberty in the distance. A nod to Miss’s Land Art peer, Robert Smithson, can be seen in a curving dock that recalls the latter’s Spiral Jetty, while plantings of trees and rocks trace the boundary of Manhattan’s shoreline during the pre-colonial era.