“I have decided to leave this insane Europe. One does not know in the morning what will happen in the evening so I have decided to come to America with my wife. America may be very materialistic but at least one’s life is guaranteed and that’s a lot in these stupid times.”

The “stupid times” of which Alexander Archipenko wrote from Berlin to the

American patron of the arts and social reformer Katherine Dreier in January

1923 seem almost innocent compared with what was to come, but Germany was already experiencing the hyperinflation that meant even a wheelbarrow full of banknotes wouldn’t pay for a newspaper. Plenty enough to convince one of Europe’s most daring and innovative artists in a daring and innovative age that his future lay across the Atlantic.

Nine months later, the 35-year-old boarded the SS Mongolia at Hamburg

with his wife Angelica and set off for New York, where he would spend the rest of his life attempting to recapture the dynamism and success of his years in Paris and Berlin – with mixed results.

“The feeling was widespread that Archipenko had developed, over the

course of a long and varied career, into an artist of eccentric tastes and wild, if not necessarily interesting or cogent, ideas,” wrote the American art critic

Hilton Kramer in 1967, three years after the artist’s death. “Encountering one of the more bizarre constructions of his later years one’s inclination was to smile, recoil, and pass quickly onto the more digestible and up-to-date works.”

That’s not to say Archipenko’s career went into terminal decline. He remained innovative and far-seeing throughout his life and one could even argue he was an artist who ultimately outpaced time until he was too far ahead for his own good.

Take the Archipentura, for example. Unveiled in 1928 as part of an exhibition at the Anderson Galleries in New York, it was a frame seven feet high and three feet across supporting 110 horizontal rollers covered in canvas that, powered by an electric motor, rotated to reveal five different artistic images. There were three cubist studies of the female form, an abstract piece and a final image of a human figure standing over a red number seven with a dedication to “T Edison and A Einstein”.

In his written contribution to the exhibition catalogue, Archipenko, who

billed himself as a “sculptor and inventor”, detailed how the machine was if not inspired by then certainly related to Einstein’s Theory of Relativity at a

time when Einstein was at the height of his celebrity.

“I know that my knowledge of science does not suffice to understand the Einstein theory in all its aspects but its spiritual substance is clear to me,” he

wrote. “I have a suspicion that the theory of relativity was always hidden in art, but Einstein with his genius has made it concrete with words and units.”

Archipenko was forward thinking in his willingness to combine art with the

world of science and engineering and particularly with his desire for art to

embrace commerce. In 1929 he became the first artist to stage a solo exhibition in a department store, taking over the fifth floor of Saks in Manhattan then devising for them a set of window displays facing Fifth Avenue that usurped what he called the “ornamentation and imitation” of traditional displays. He devised instead “a decorative structure employing

rhythmic architectural motifs”, in this case burnished metal panels bent into

abstract shapes around mannequins showing evening gowns. The windows’

reception among shoppers and art critics was cool and the commission was not repeated, but surviving photographs reveal how the windows would not look remotely out of place in the 21st century.

He was confident that the Archipentura, with its revolving series of images, had a future in advertising. Alas, despite being generally well received at

the Anderson Galleries show and subsequent exhibitions across the US, in

1935 Archipenko returned to New York from a trip to California to find that a

new caretaker at his apartment building had found the disassembled Archipentura stored in the basement, assumed it was junk and thrown it out.

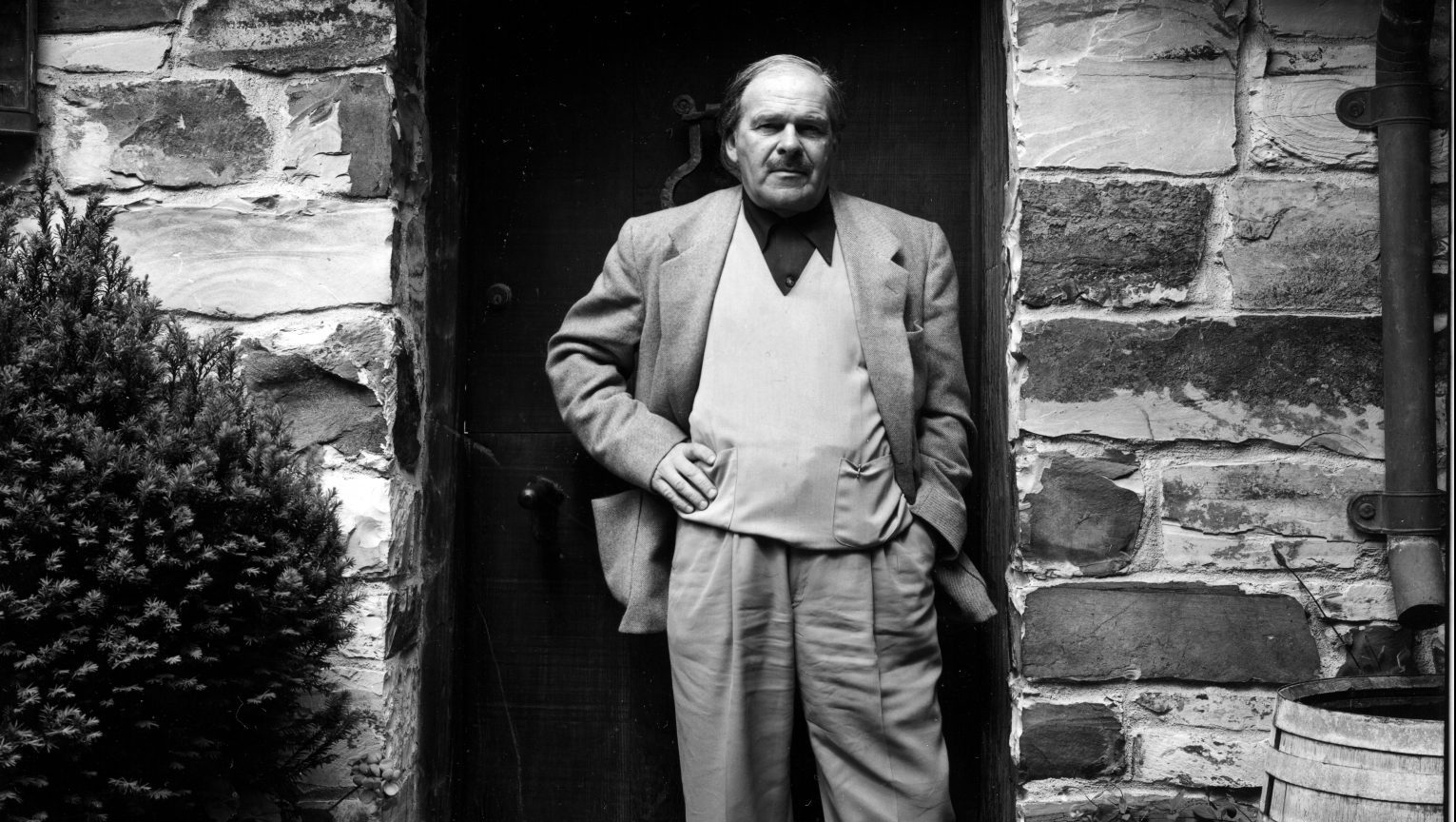

If Archipenko had believed that the US offered a warmer reception for his

adventurous, avant-garde ideas than Europe, his limited success only sealed

his status as an outsider, a man aloof from the nation he’d chosen to make his home.

“The sad truth seems to be that he never found in this country the moral or

aesthetic equivalent of that marvellous inspiration he derived from the School of Paris in its greatest epoch,” wrote Kramer. “America forced the artist to turn inward and this proved, alas, not to be a fertile territory for an artist of Archipenko’s talents and temperament.”

He always maintained that, born and raised in Kyiv, he came from a country without an art tradition, a liberating absence of constricting praxis he may

have believed he’d find in a young nation like the US.

“There is no nationality in my creations,” he said. “In that respect, I am no more Ukrainian than I am Chinese.”

Even if his star did fade after his move across the Atlantic, Archipenko’s artistic contribution prior to 1923 ensures a deserved place in the canon of great 20th-century artists.

He was expelled from the University of Kyiv when, caught up in the revolutionary fervour in the region in 1905, he attacked the art department for being out of touch. Three years later he moved to Paris, the epicentre of the European art revolution, and thrived, inspired by the ancient art he saw in the Louvre from Greece and Byzantium to produce the abstract human figures for which he became renowned.

What particularly set his work apart was his willingness to incorporate colour and space into his pieces, making him the first sculptor to master cubism.

“Space is an element of sculpture,” he said. “This is a psychological thing; those parts which are absent have the form of the absent object which I want to present. I draw a parallel between space and the pause in music, which has as much meaning as sound itself.”

By 1920 he was at the cutting edge of the avant-garde, staging solo shows at the Venice Biennale and Der Sturm in Berlin, as well as featuring prominently at the 1913 Armory Show in New York. For whatever reason, however, and despite producing new art right up until his death, Archipenko’s critical momentum slowed after his move across the Atlantic.

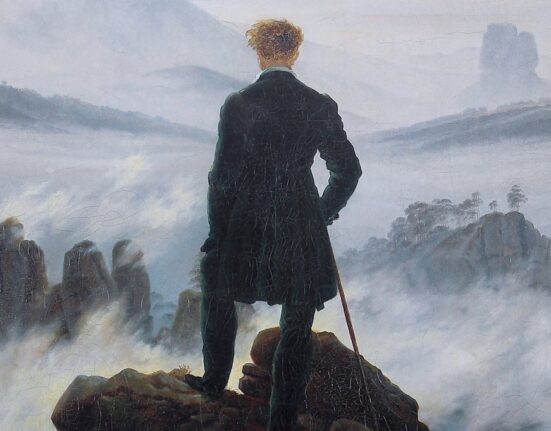

Perhaps he became the ultimate outsider, displaced from his home continent and ahead of his time in the work he produced. After all, today we can barely walk down a city street without some version of the Archipentura trying to sell us things. Nonetheless, his contribution to both early 20th-century art and the design of the modern world should not be underestimated.

“Hitherto sculpture has limited itself almost exclusively to being melody,” wrote Guillaume Apollinaire in the catalogue of the 1914 Der Sturm exhibition in Berlin.

“In Archipenko’s works it seems to grow into a great harmony.”