The Mediterranean island of Cyprus has long been a geopolitical crossroads, a prize contested by empires and a meeting point of peoples, religions — and money.

An astonishing flood of foreign money, mostly Russian, has poured into the island over decades, bringing wealth to a few but leaving Cyprus with a reputation as a shady financial hub.

Now, an investigation by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, Paper Trail Media and 67 media partners reveals how Cyprus, at the east end of the Mediterranean nearest Turkey, Syria and Lebanon, plays an even bigger role than was commonly known in moving dirty money for Russian President Vladimir Putin’s autocratic regime and other brutal dictators and anti-democratic actors.

Among them: Syria’s murderous rulers, whose state-owned oil company attempted to evade the United States’ ban on doing business with it by using an intermediary on the island to disguise requests for purchases from a Houston oil equipment supplier; and Kremlin associates who channeled payments through Cyprus to a prominent German journalist known for producing fawning coverage of Russia’s autocratic leader.

The product of an eight-month investigation, Cyprus Confidential stories explore Russia’s long-standing hegemony over Cyprus’ deeply intertwined worlds of politics and finance. It explains how the mighty European Union has failed to exert authority over Cyprus, a European Union member state, or to rein in a banking system bloated by illicit money. It illustrates how, as Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022, Big Four accounting giant PwC’s Cypriot unit helped Russian oligarchs shuffle their riches and undermine Western sanctions designed to cut off Putin’s war funding. As Western nations have increasingly used financial sanctions to block the flow of money that other governments use for hostile purposes, Cyprus became a cloak-and-dagger financial battleground.

The 3.6 million leaked files at the heart of the Cyprus Confidential investigation come from six financial services providers and a website company.

The providers are: ConnectedSky, Cypcodirect, DJC Accountants, Kallias & Associates, MeritKapital, and MeritServus in Cyprus. The MeritServus and MeritKapital records were obtained by Distributed Denial of Secrets. Leaked records from Cypcodirect, ConnectedSky and i-Cyprus were obtained by Paper Trail Media. In the case of Kallias & Associates, the documents were obtained from Distributed Denial of Secrets, which shared them with Paper Trail Media and ICIJ. DJC Accountants’ records were obtained by Distributed Denial of Secrets and shared by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project. The partner organizations shared all the leaked records in the project with ICIJ, which structured, stored and translated them from several languages before sharing them with journalists from around the world. Additional records came from Latvia-based Dataset SIA, which maintains the i-Cyprus website, through which it sells information about Cyprus companies, including Cyprus corporate registry documents.

ICIJ assembled a team of more than 270 journalists from 54 countries and one territory and provided access to the leaked records through its secure document-research platform, Datashare. ICIJ and Paper Trail Media organized and coordinated the project through ICIJ’s secure communications platform, I-Hub. As part of the Cyprus Confidential project, ICIJ’s data and research team combed the records with partners to find sanctioned Russian oligarchs, billionaires and politically exposed persons (PEPs), and reveal their offshore holdings.

The leaked internal records, dating from the mid-1990s to April 2022, include confidential background checks, organizational charts, financial statements, bank account applications and email messages.

Together, the documents offer a penetrating look inside the rogue financial system that has helped empower some of the West’s most determined foes. Critics say the island’s dependence on Russian and other foreign money carried consequences only now being realized.

“When the Russians came to Cyprus, they brought not only Russian corruption, they brought Russian organized crime, they brought Russian agents of the Russian intelligence services,” says Boris Demash, a Russian longtime resident of Cyprus and critic of Kremlin influence.

Meanwhile, says Cyprus-based economic historian Alexander Apostolides, the island’s politically wired professional firms seem to find ways to “do the things that are either illegal or at least unethical.”

When the Russians came to Cyprus, they brought not only Russian corruption, they brought Russian organized crime, they brought Russian agents of the Russian intelligence services — Boris Demash, Kremlin critic

In response to questions from ICIJ, a Cyprus government spokesperson said that, “since 2013, Cyprus has engaged in persistent efforts and has managed to stabilize its banking sector and become a top jurisdiction for both anti-money laundering and sanctions enforcement.” He said the country today has “a strong and robust framework in place and our banking sector implements one of the strictest regulatory frameworks internationally,” a view supported by a 2015 European Commission review of Cyprus’ economy and financial sector, a 2022 review by the Council of Europe’s main anti-money laundering advisory group, and several U.S. State Department assessments, including one last year that found the country’s “traditional banking sector is significantly less vulnerable to money laundering than it was just a few years ago.”

The spokesperson also said that Cyprus now places in the top 25% of international anti-money laundering enforcement rankings, while the banking system has been “deleveraging significantly” by reducing exposure to Russian deposits, which stood at only about 4% of total deposits at the end of 2021.

Under the influence

As Cyprus Confidential illustrates, shady finance has been the province of the highest levels of Cyprus’ government and finance. The island’s economic system, known as the Cyprus model, relies on an oversized financial sector with some of the European Union’s weakest financial disclosure laws, an indulgent central bank — and a tsunami of more than $200 billion in Russian investment that has bought its oligarchs vast influence.

Typifying the clannishness that has made it all possible is Nicos Anastasiades. A lawyer who founded a major offshore services practice that drew Russian clients, Anastasiades served as Cyprus’ president from 2013 until early 2023. A 2019 investigation by ICIJ media partner OCCRP found that before Anastasiades took office, partners in his law firm served as officials of shell companies linked to massive suspected money laundering operations, including deals linked to Putin allies.

Upon taking office, Anastasiades left the firm to two daughters and other partners and traveled to Moscow, where he met with Putin and secured agreements promoting closer economic and financial ties.

OCCRP said its documents did not contain any specific evidence that the firm or the firm’s employees broke any laws or committed any crimes. In a statement to ICIJ, the firm said: “We categorically would like to state that none of the members of our law firm have been implicated in any wrongdoing. These allegations are entirely unfounded and lack merit.”

The firm added that in the wake of the OCCRP report, Cyprus’ anti-money laundering agency conducted a “comprehensive investigation, which involved a meticulous examination and analysis of the data presented to them” and issued a 2019 report “fully exonerating our firm and confirming that there were no indications of any involvement in illegal or suspicious activities.” As part of a letter to ICIJ, Anastasiades said he has had no “absolutely no active involvement” in the firm since 1997 and transferred all his shares to his two daughters upon taking office in 2013.

Underpinning the project is ICIJ’s data analysis, with original findings that illustrate Cyprus’ indispensable role in moving oligarch wealth either to be hidden outside Russia as yachts, real estate and financial instruments, reinvested in Russia, or used to undermine democratic institutions in the West.

ICIJ found that the Cyprus professional services firms were working on behalf of 25 Russians who came under Western or Ukrainian sanctions after Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea and war in Donbas.

ICIJ’s data analysis, which matches names found among millions of documents against public records and private databases, found an additional 71 Russian clients who have come under sanctions since February 2022, bringing the total to 96 sanctioned individuals.

Among the sanctioned Russian clients, ICIJ identified 44 PEPs, the public officials, their relatives or others linked to state-owned companies or organizations deemed to merit added scrutiny because of a heightened risk involving corruption or other illicit activity. What’s more, among the 104 Russian billionaires Forbes magazine identified in 2023, two-thirds — a total of 67 individuals — also appear in Cyprus Confidential documents, along with their family members, as clients of the island’s professional services providers.

All told, ICIJ found in these leaked documents nearly 800 companies and trusts registered in secrecy jurisdictions that were owned or controlled by Russians who have been sanctioned since 2014. (Secrecy jurisdictions are countries and territories that provide a low-tax regime and corporate ownership anonymity, limit access to company documents and can be more lenient toward financial crime.) The analysis showed the professional firms also worked for Russian-controlled companies registered in the British Virgin Islands, the Channel Island of Jersey, the Isle of Man in the Irish Sea, Liechtenstein, Hong Kong and elsewhere. While many of the registered entities are shell companies with no employees or operations, some are subsidiaries of industrial giants — such as steelmaker Evraz, which supplies most of the train rails that Russia uses to transport arms and ammunition to its troops in Ukraine.

The most recent Cyprus Confidential leaked records are dated April 2022 (with a few incidental records dated afterwards), so they don’t show whether any of the providers continued to work with clients hit with Western sanctions since then.

Taken together, the project’s 3.6 million documents — despite representing a small fraction of Cyprus’ offshore industry records — reveal the EU member state to have been a massive financial hub for Putin’s Russia. The documents also provide a glimpse into the oligarchs’ lavish lifestyles: their superyachts, their priceless art collections of Matisse, Monet and Lucian Freud, and their private concerts featuring Amy Winehouse, the Red Hot Chili Peppers and other rock stars.

The enablers

The investigation reveals, for instance, how global accounting giant PwC, formerly known as PricewaterhouseCoopers, put its Cyprus office and its 1,100 employees at the service of Putin allies amid Russia’s bloody invasion of Ukraine. The project provides an in-depth look at how PwC helped Alexey Mordashov, one of Russia’s richest industrialists, transfer a $1.4 billion investment out of his name in a bit to elude EU sanctions.

The Cypriot Ministry of Finance is aware of the share transfers, and a criminal investigation is underway, a ministry official told ICIJ in November.

“All information and regulatory notifications with respect to the share transfer were duly disclosed to the relevant authorities and made public to the extent legally required,” Mordashov spokesperson Anastasia Mishanina said in a written statement. “Not once in his long career did Mr. Mordashov, or any of the companies he runs, breach any laws, whether in Europe, Russia, or any other jurisdictions.”

Around the same time, PwC Cyprus helped transfer another $100 million for a pair of Russian oligarchs whom the U.K. would soon declare part of the “cabal of selected elite” helping Putin wage his war on Ukraine.

In all, ICIJ found that PwC Cyprus worked with at least 12 of the 25 Russians who were already subject to sanctions by Western governments or Ukraine after Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea and the war in Donbas. But it took PwC until a few months after Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine to announce it was leaving Russia and ordering its affiliates to cease working for sanctioned clients. “Any sanction on specific Russian entities or individuals that is passed anywhere in the world will be applied everywhere in the world,” the accounting firm stated on its website.

And, the project reveals that PwC Cyprus partners who left the firm to form a new provider also took over the administration of companies controlled by the pair of oligarchs the U.K. listed among Putin’s “cabal.” The firm, called Kiteserve, had office space in the same building as PwC’s offices in Limassol, Cyprus. Kiteserve severed ties only after the U.K. sanctioned the pair last year.

Cyprus Confidential illustrates how PwC and other accounting firms profit from their global reach while distancing themselves, when needed, from their largely autonomous local units or their offshoots.

Citing the need to maintain confidentiality, PwC declined to comment on its business with individual clients. It added that it complied with EU and United Nations sanctions before Russia’s February 2022 invasion of Ukraine and has since severed ties with 60 clients as a result of the company’s new Russia-related sanctions policy. “PwC’s internal standards are reviewed and updated to reflect both lessons learned and changing circumstances,” Mike Davies, a PwC spokesperson, said in a statement, “and we do not hesitate to take action when our standards are not met. Any allegation of non compliance with applicable laws and regulations is taken very seriously, investigated and appropriate action is taken if necessary.”

The firm said its Cyprus office had “pivoted to a new economic model fit for the future, transforming its business” and pointed to the office’s annual report for 2022. PwC Cyprus’ fiscal 2023 annual report, released in September, cited a “significant contraction” in business related to implementing the global sanctions policy.

Not long after the invasion of Ukraine, PwC joined an exodus of Western companies, declaring that it was separating itself from its Russian affiliate.

London calling

The Cyprus Confidential investigation reveals that another Cyprus firm founded by former PwC partners, Abacus Ltd., is at the center of a legal dispute involving Russian billionaire Petr Aven. Filed by the U.K.’s National Crime Agency, which oversees international financial investigations, the civil case accuses Aven of evading sanctions by using Abacus and European banks to shunt wealth beyond the reach of Western sanctions.

The previously unreported court records were obtained by U.K. nonprofit Spotlight on Corruption through a court petition and shared with ICIJ. The separate, and larger, Cyprus Confidential leak provides a broad view of Aven’s wealth and Abacus’ central role in managing it.

Aven, who helped build Alfa Group into one of Russia’s largest financial conglomerates, was named in the 2019 Mueller report on Russian interference in the 2016 U.S. presidential election as offering to act as an intermediary between Putin and Donald Trump’s 2016 presidential transition team. Aven was among the oligarchs called to a meeting with Putin in the Kremlin on Feb. 24, 2022 — the day Russia invaded Ukraine. Alfa Group was later reported to be providing insurance to the Kalashnikov arms-making conglomerate and the Russian armed forces during the war.

In addition, ICIJ found that Abacus provided services to another 60 Cyprus-registered companies owned or controlled by other Russian oligarchs over the years, often in tandem with PwC.

The fixer

The U.K. has accused a prominent Cypriot corporate services provider, Demetris Ioannides, of having “knowingly assisted sanctioned Russian oligarchs to hide their assets in complex financial networks.”

The ICIJ data analysis shows that Ioannides’ firm, MeritServus, handled the day-to-day business of more than 100 Cyprus companies and trusts owned or controlled by Russian oligarchs, including Kremlin propagandist Konstantin Malofeyev, who was already the subject of Western sanctions.

Now, Cyprus Confidential records reveal that MeritServus had an extensive relationship with one of Russia’s most prominent oligarchs, Roman Abramovich. A billionaire long based in the U.K., Abramovich in some ways typified Western elites’ embrace of Putin’s oligarchy. Worth $9 billion, Abramovich has been a member of Putin’s inner circle since the late 1990s. He became widely known in the West for his fleet of yachts and as the longtime owner of Chelsea Football Club, the U.K. professional soccer team.

ICIJ’s analysis found that MeritServus helped administer no fewer than 14 Cyprus-registered trusts owned or controlled by Abramovich. Sometimes the work was done in tandem with the Cyprus branch of Big Four accounting giant Deloitte, which Ioannides had founded earlier in his career. MeritServus also provided services to Abramovich companies registered in secrecy jurisdictions including the Isle of Man, Jersey and, mostly, the British Virgin Islands, where the bulk of Abramovich-owned companies — nearly 100 — were registered, ICIJ found.

Cyprus Confidential also shows that an Abramovich-controlled entity sold a highly profitable stake in an advertising company to an entity controlled by Sergey Roldugin. A classical cellist and longtime friend of Putin, Roldugin was exposed in the Panama Papers as a major figure in a network that moved over $2 billion through banks and shell companies. The U.S. Treasury sanctioned Roldugin in June 2022, describing him as a “custodian of President Putin’s offshore wealth.”

The project raises questions for the Chelsea Football Club over how Abramovich, its onetime owner, funded the club’s success.

The files reveal a decade-long pattern of payments worth tens of millions of British pounds, routed through offshore vehicles belonging to Abramovich and apparently omitted from Chelsea’s financial accounts.

Representatives of Abramovich did not return requests for comment.

Dealing with despots

Perhaps most striking, the Cyprus Confidential project shows how the island’s economic model has contributed in small but crucial ways to some of the century’s great historical harms.

The investigation exposes detailed discussions between Syria’s state-owned oil company and a Cyprus-registered intermediary about buying drilling equipment made by the Houston-based manufacturer NOV Inc.

It presents evidence that the Syrian Petroleum Co. and a Cyprus intermediary prepared to conduct at least five transactions between 2014 and 2019 to obtain NOV equipment.

The SPC is owned by Syria and controlled by the government of Bashar Assad. The U.S. has accused his regime of genocide and in 2011 imposed a strict ban on exports to Syria, specifically naming the SPC in the sanctions.

New York Stock Exchange-listed NOV stated in a 2017 securities filing that it had exited business with Syria at least three years earlier. Documents show Cyprus-based H.A. Cable Export Co. Ltd. and the SPC continued to discuss purchases of NOV equipment to Syria after that date. The documents were obtained from Demetrios A. Demetriades LLC, a Cypriot law firm appearing in ICIJ’s 2021 Pandora Papers project and now revisited as part of the Cyprus Confidential investigation.

In June 2014 correspondence, the SPC wrote H.A. Cable Export that it was getting in touch to buy parts “of American origin” at the suggestion of “National Oilwell Varco,” as NOV was known at the time. Two years later, the SPC said that it was directing a query about acquiring NOV equipment to H.A. Cable “due to USA sanction imposed on Syria.” In 2019, the Syrian company urged H.A. Cable to buy NOV pumps and drawworks “as soon as possible.”

NOV’s chief compliance officer, Brent Benoit, told ICIJ in an email that the company reviewed its transactions and found no evidence that NOV was involved in any sales to H.A. Cable during the period in which the discussions between H.A. Cable and the SPC occurred. He did not address a question about the letter the SPC said it had received from NOV in 2014 referring it to H.A. Cable.

With the help of Russia, Iran and a steady flow of oil revenue, Assad has since turned the tide in Syria’s civil war in his favor.

Among other revelations, the Cyprus Confidential documents show how the island has turned itself into a magnet for a motley collection of the rich and powerful seeking an edge in ethical gray areas. Among the clients exposed in Cyprus Confidential are: a lawyer involved in selling spyware to some of the world’s most brutal regimes; a former senior European politician who went to work for a now-sanctioned Russian oligarch, the digital magazine Reporter.lu reported; and a sanctioned Russian oligarch who secretly helped finance a Holocaust movie alongside European taxpayers, report news outlets Reporter.lu, Knack, Le Soir and De Tijd.

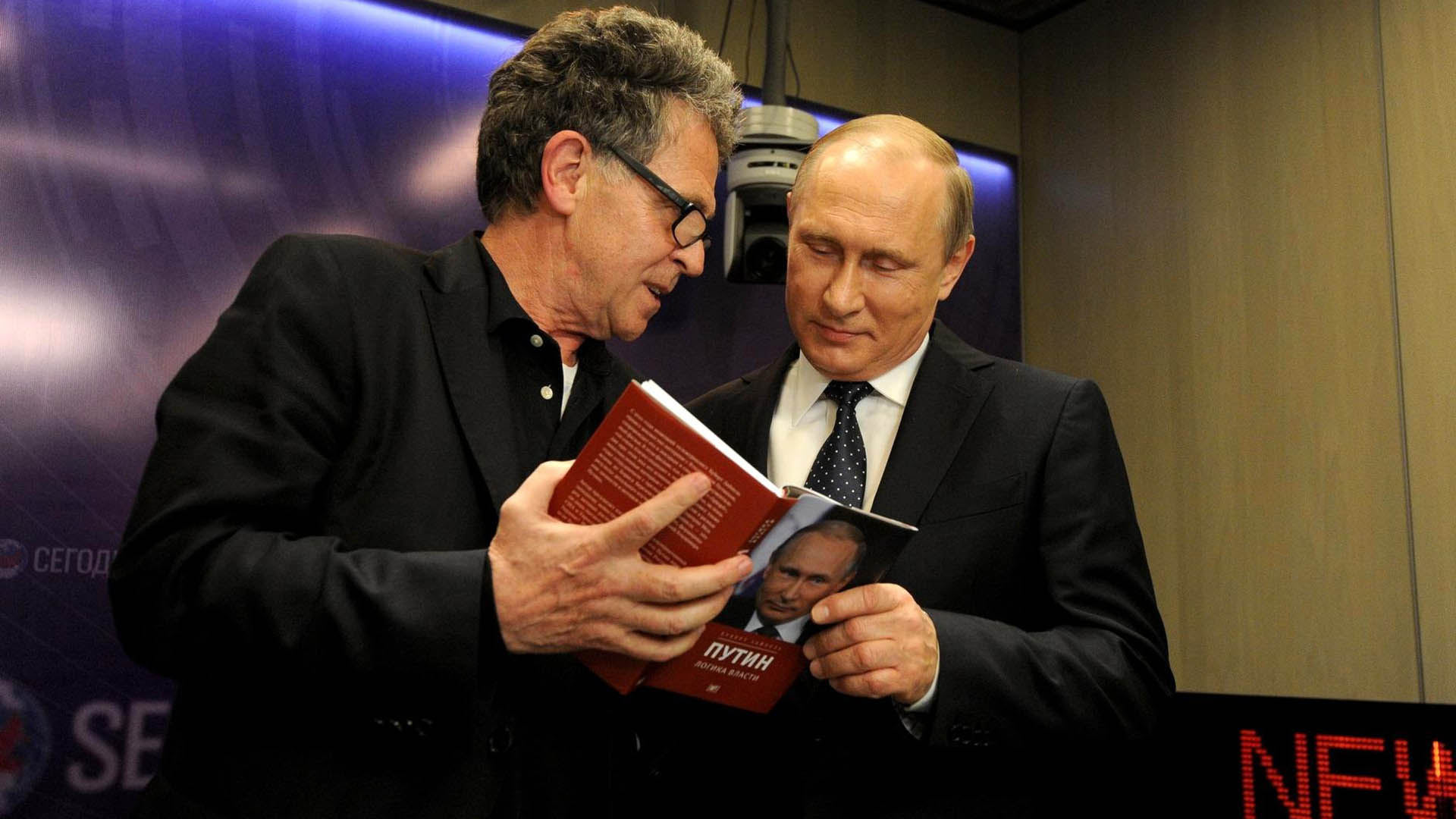

Putin’s author

Among the many Westerners who have built a career explaining Russia and its autocratic leader is Hubert Seipel, a German journalist, author and television personality. He forged his brand touting his unparalleled access to the Russian president, promoting images of them hunting deer together in Siberia and cruising through Moscow in the back of a limousine. The portrayals that Seipel, who is in his 70s, turned out were decidedly sympathetic but also won him awards and accolades for portraying Russia as something other than a world menace.

Leaked documents that are part of Cyprus Confidential now reveal that, in the past five years, Seipel has agreed to receive about $700,000 as a “sponsorship” from a shell company linked to now-sanctioned oligarch Mordashov. Dmitry Fedotov, a lawyer working for Mordashov’s steel conglomerate, Severstal, served as a witness to the agreement on behalf of the sponsor, the records show.

A handwritten note on a 2018 document says the sponsorship was “for writing a book on [the] political environment in the Russian Federation.” Another note on the same record also referred to a 2013 agreement for “Putin biography.” Seipel has published two German books about Putin, with titles that translate to “Putin: Inner Views of Power” (published in 2015) and “Putin’s Power” (2021).

The “sponsorship” agreement, uncovered in the leaked financial records by German reporters working for Paper Trail Media, Der Spiegel and ZDF, provides a striking example of the breadth and sophistication of Russia’s propaganda machine abroad.

Over the years, Germany’s media and publishing industries have sung Seipel’s praises and anointed him one of the country’s leading analysts of Russia.

For his part, Seipel has vehemently denied being on the Kremlin’s payroll. When pressed on the matter during a 2021 radio interview, he replied with an emphatic “No!”

In response to questions from Paper Trail Media, Seipel acknowledged Mordashov’s “support” for his books but defended his work as unbiased. “[N]o specific factual errors were found in any of the books,” he said.

Records show that the paperwork for the transactions involved in the book deal was prepared by Cypcodirect and PwC Cyprus.

Contributors: Spencer Woodman, Matei Rosca, David Kenner, Dean Starkman, Tanya Kozyreva, David Rowell, Whitney Joiner, Fergus Shiel, Delphine Reuter, Karrie Kehoe, Jelena Cosic, Jesús Escudero, Agustin Armendariz, Miguel Fiandor, Denise Ajiri, Emilia Diaz-Struck, Scilla Alecci, Brenda Medina, Eve Sampson, Richard H.P. Sia, Kathleen Cahill, Angie Wu, Tom Stites, Hamish Boland-Rudder, Joanna Robin, Carmen Molina Acosta, Hans Koberstein (ZDF), Bastian Obermayer, Frederik Obermaier, Sophia Baumann and Timo Schober (Paper Trail Media/Der Spiegel), Kira Zalan (OCCRP), Luc Caregari (Reporter.lu)