Looking at Salvador Dalí’s bizarre, inscrutable canvases, it’s hard to imagine his inspirations as anything earth-bound. Like any self-respecting Surrealist, the artist drew ideas from dreams, translating those visions into strange symbols and motifs. Or maybe he didn’t need the creative prompts at all: “A true artist is not one who is inspired,” he once declared, “but one who inspires others.”

But a major exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston is making the case that Dalí, while mining his dream reality, was also looking to tradition. “Dalí: Disruption and Devotion,” the first-ever show of the Spanish painter’s works at the museum, uncovers how the artist subtly and directly engaged with European art and artists including El Greco, Johannes Vermeer, Artemisia Gentileschi, and Albrecht Dürer.

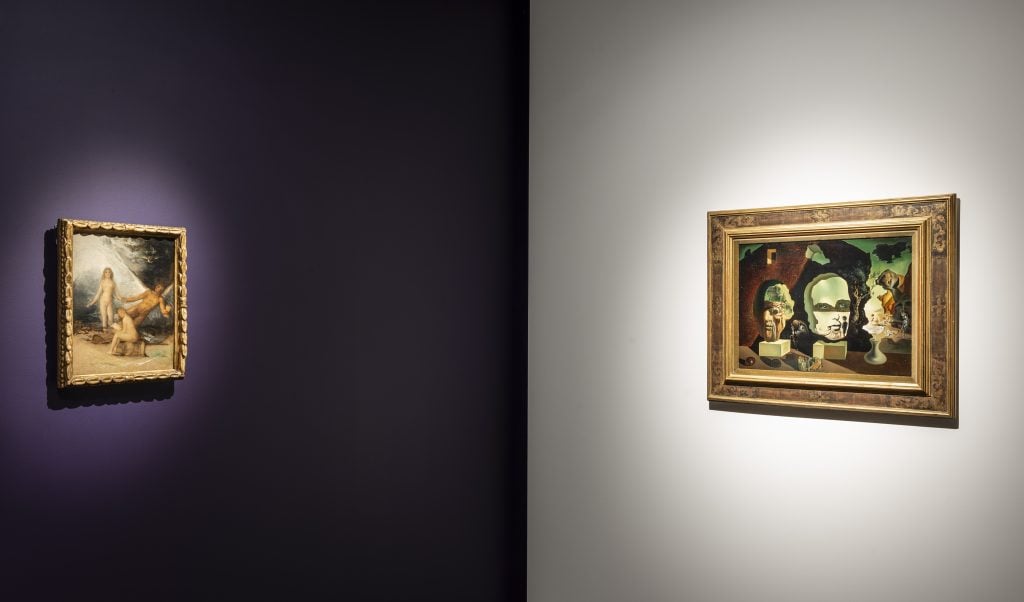

Installation view of “Dalí: Disruption and Devotion” at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Photo: © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Nearly 30 Dalí artworks, on loan from the Dalí Museum in Florida, are on view alongside pieces from the MFA Boston’s European holdings. They are variously paired or grouped by theme and subject matter to newly illuminate the work of the celebrated Surrealist.

For instance, Francisco Goya’s “Los Caprichos,” his 1799 series of prints detailing the dark side of civilized society, are arrayed with Dalí’s reinterpretations, which put a playful spin on Goya’s subversive etchings. Meanwhile, Dalí’s Sainte Hélène à Port Lligat (1956), in which he depicted his wife Gala as Saint Helena, is matched with El Greco’s Saint Dominic in Prayer (ca. 1605) to highlight their shared meditation on solitude and supplication.

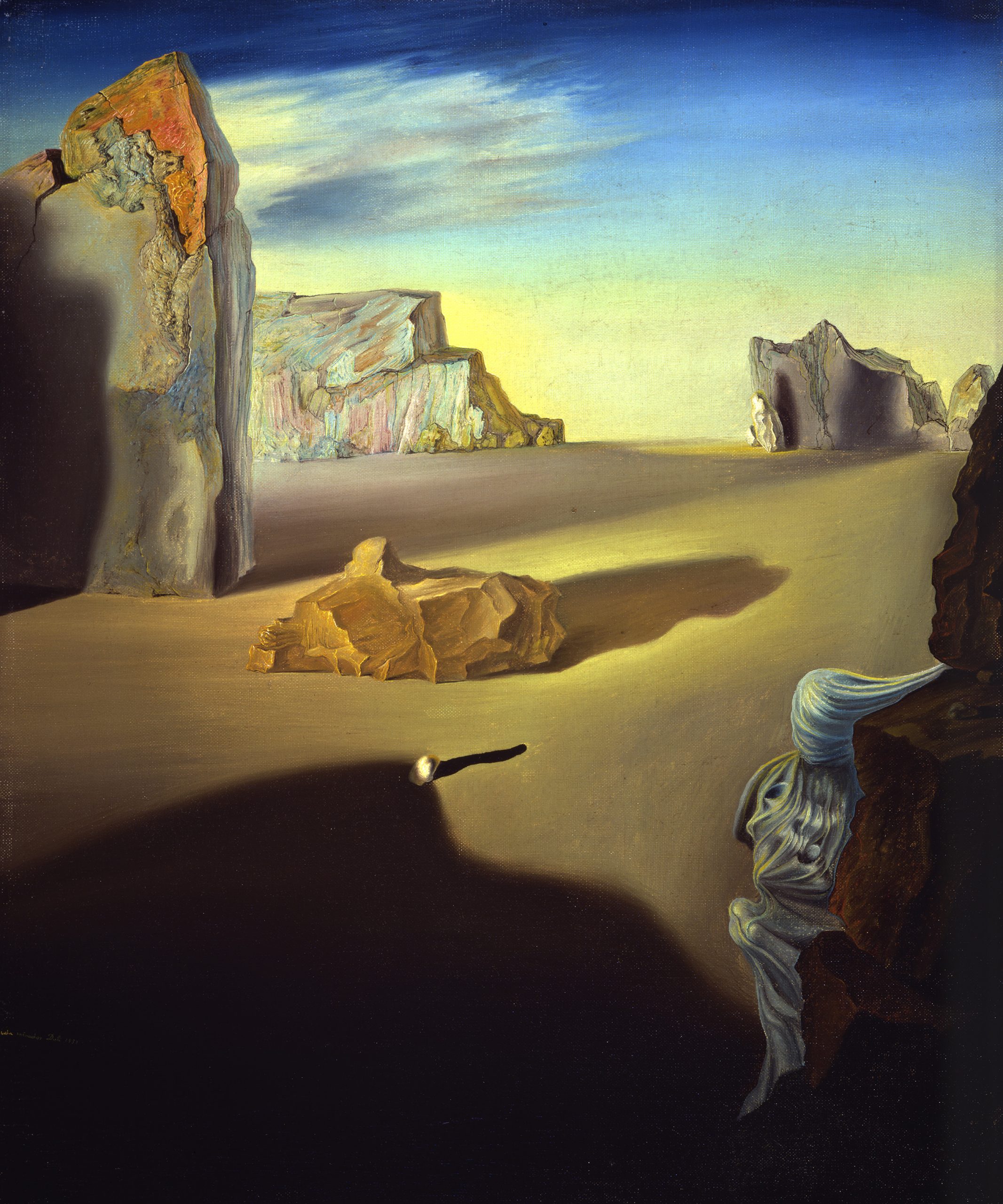

Salvador Dalí, Morphological Echo (1936). Collection of The Dalí Museum, St. Petersburg, FL. © 2024 Salvador Dalí, Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, Artists Rights Society. Photo courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

The exhibition will also uncover how European art history runs through Dalí’s own works. In Morphological Echo (1936) and Nature Morte Vivante (Still Life-Fast Moving) (1956), viewers might see hints of 17th-century Dutch still lifes filtered through a Dalí-esque lens. The Ecumenical Council (1960), the painter’s towering ode to spirituality, is riven throughout with Renaissance references, notably to Michelangelo’s The Last Judgement in its portrayal of God.

Salvador Dalí, The Ecumenical Council (1960). Collection of The Dalí Museum, St. Petersburg, FL. © 2024 Salvador Dalí, Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, Artists Rights Society. Photo: © Doug Sperling and David Deranian, 2021, courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Surprisingly, Dalí also painted himself into Ecumenical Council. In the work’s bottom-left corner, he is depicted by an easel, his brush held aloft, and his gaze fixed on the viewer—a pose recalling Diego Velázquez’s own self-portrait in his celebrated masterpiece Las Meninas (1656), complete with upturned mustache.

Salvador Dalí, Velázquez Painting the Infanta Marguerita with the Lights and Shadows of His Own Glory (1958). Collection of The Dalí Museum, St. Petersburg, FL. Photo courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Dalí famously revered Velázquez. He echoed the Spanish master’s technique and mastery of light in works such as The Image Disappears (1938), and paid homage in Velázquez Painting the Infanta Margarita with the Lights and Shadows of His Own Glory (1958). A reproduction of Las Meninas also hung in his studio. Writing in 1976, Dalí mused: “Since Impressionism, the entire history of modern art has revolved around a single goal: reality. And this leads us to ask: what’s new, Velázquez?”

At the MFA Boston, Dalí’s Velázquez Painting is paired with Velázquez’s Infanta Maria Theresa (1653), a late portrait by the 17th-century artist, its colors and brushstrokes still fresh.

Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez, Infanta Maria Theresa (1653). Photo: © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

“Dalí: Disruption and Devotion” opens as Surrealism celebrates its centennial this year. Marking the moment are exhibitions from the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium’s blockbuster “Imagine! 100 Years of International Surrealism” to spotlights on artists Remedios Varo and Dora Maar, which, like MFA Boston’s Dalí outing, are shedding new light on the movement’s legacy.

Installation view of “Dalí: Disruption and Devotion” at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Photo: © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

“The Surrealist movement, announced by André Breton in 1924, is 100 years old,” said Frederick Ilchman, the museum’s curator of paintings, in a statement. “The MFA’s exhibition, using superb loans from the Salvador Dalí Museum in St. Petersburg, Florida, offers a timely opportunity to reconsider the most famous Surrealist in terms of the historical artists he deeply admired.”

“Dalí: Disruption and Devotion” is on view at MFA Boston, 465 Huntington Ave, Boston, Massachusetts, through December 1.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook: