Men in exile feed on dreams of hope.

Aeschylus, Agamemnon

I

Exile has always been a powerful theme in myth and history: Adam was exiled from Eden, Moses from Israel, Dante from Florence. Paris in the 1920s and 1930s was the center of creativity in the arts, and many painters gravitated there, discovering new forms and movements: Cubism, Abstract and Surrealist art. But events moved rapidly in Europe and forced the artists to make life-changing—and life-saving—decisions. Between 1938 and 1940 Germany had murdered Jews and burned synagogues in Kristallnacht; annexed Austria and the Sudetenland; invaded Belgium and Holland; and occupied France. Under the Nazi regime the innovative work of these artists was condemned as “Degenerate” and publicly burned.

When World War Two began the close-knit culture of French painters broke up and fourteen major artists escaped from France to America. Six were French: Duchamp, Léger, Masson, Tanguy, Ozenfant and the Surrealist ringmaster Breton; five were Russian-Polish: Chagall, Lipchitz, Zadkine, Kisling and Tchelitchew; Ernst was German, Dalí was Spanish and Mondrian Dutch. They had to experience, often for the second time, the trauma of dislocation, and adjust to a new country, language and culture. They didn’t know if they would ever again see France, their families or their friends. Duchamp, Tanguy and Mondrian did not return to Europe after the war and died in America.

Many practical and financial factors, apart from the mortal danger of remaining in France, influenced their decision to escape. Ernst, Léger, Masson, Zadkine and Kisling, who’d fought in World War One, didn’t want to repeat that horrific experience, lose more creative years and be unable to exhibit their work. As the French poet Paul Eluard wrote, they had “Le dur désir de durer” (the strong wish to endure). Those who emigrated were much better off if they had they made previous visits to America, if their art was known there, if they had valuable contacts with patrons and galleries, if they had enough money to survive and if they knew English. Some, like Chagall, Masson, Tanguy and Breton, clung to their French identity and refused to learn the new language. To paraphrase W. H. Auden, a self-exile, France was the name of their own tongue and what they spoke when they were young.

The Jewish artists had no choice and would have been killed if they’d remained in Europe. Chagall, Lipchitz, Zadkine and Kisling had been foreigners in France long before they arrived in America. Other Jewish artists, Modigliani and Pascin, had died. Soutine remained in France, went into hiding and sometimes had to sleep outdoors in the forests. Desperately ill and unable to have an essential operation, he died from a bleeding ulcer in 1943. Kisling had again volunteered to fight in World War Two, was wounded on the Somme and discharged from the army after the French surrendered. He reached America, lived near Aldous Huxley in southern California and returned to France in 1946.

The artists, expecting a German invasion of France, were eager to sell their work and escape, and they all pursued the wealthy Peggy Guggenheim. Ruth Brandon reports that “during the dangerous days before and just after the fall of France she had made it a point of honour to buy a painting a day from working artists, which was certainly good for the Guggenheim collection, but also saved a great many painters.” Peggy helped Ernst, Duchamp, Masson and Breton escape from Nazi-occupied France, and in New York she became the most influential patron, the creator of reputations and of financial success. Peggy was repaid with sex as well as with art. Sexually insatiable—“I demanded everything I had seen in Pompeii frescoes”—with no moral scruples or moral restraints, she slept with whoever took her fancy and racked up more than 30 lovers.

Peggy Guggenheim

In The Go-Between, L. P. Hartley observed, “The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there.” The exiles always carried the shadow of their old country with them and kept their precious memories of France. They had a fresh and original view of America—most notably in Mondrian’s blues-titled Broadway Boogie Woogie (1943)—and painted it with an imaginative perception that was quite different from the native viewpoint.

The artists who left felt guilty and lost moral authority; those who remained were courageous and gained moral stature. As Ernst said of Eluard, “He is my close friend and brother. He could have come, like we did. Be safe. But he stayed.” Picasso felt his identity as an Andalusian and Catalan was stronger during his exile from Franco’s Spain than when he actually lived among his people. Though he could not exhibit his art during the Occupation, and risked prison, deportation and even execution by the fascists, he decided to remain in France. After the liberation he joined the Communist Party in October 1944, though he challenged its cultural platform. He admired the Communist authors—Eluard, Louis Aragon and René Char—who joined the Resistance and risked their lives, and the Romanian-Jewish writer Tristan Tzara who helped run the Resistance in Toulouse.

Chagall’s biographer Jonathan Wilson writes that “war on the horizon always draws people out of cities, away from threatened borders, and into the heart of the countryside, where the illusion of safety can be temporarily sustained.” After the German conquest, France was divided into the northern zone under the Nazi military Occupation and the nominally free southern zone under the Vichy regime of Marshal Philippe Pétain. By then every train to the Mediterranean port of Marseilles was crowded with refugees escaping from Paris, where the Gestapo and their French collaborators raided homes at midnight, and acted with unexpected and life-threatening efficiency.

The Franco-German Armistice of June 1940 stipulated that enemies of the Reich had to be surrendered on demand, which endangered the lives of the artists. That month the American Emergency Rescue Committee was formed to arrange the escape of many prominent cultural figures who’d been trapped during the Nazi Occupation, and get them out of France before the Gestapo captured and killed them.

The head of this organization in France was Varian Fry (1907-67), a young journalist with close connections to Left-wing political groups, who had witnessed anti-Semitic brutality in Berlin in 1935. Jonathan Wilson describes him as “conservative in both manner and appearance, a Harvard classics major who enjoyed bird-watching and wine tasting.” Fry rented the Villa Air Bel outside Marseilles to provide a home for the frightened artists. Fighting both the Vichy government and the hostile American consul in Marseilles, Fry courageously saved Ernst, Chagall, Duchamp, Léger, Lipchitz, Zadkine, Breton and some 2,000 other refugees by providing money and documents (both real and forged), before he was expelled by the French police in August 1941.

Varian Fry

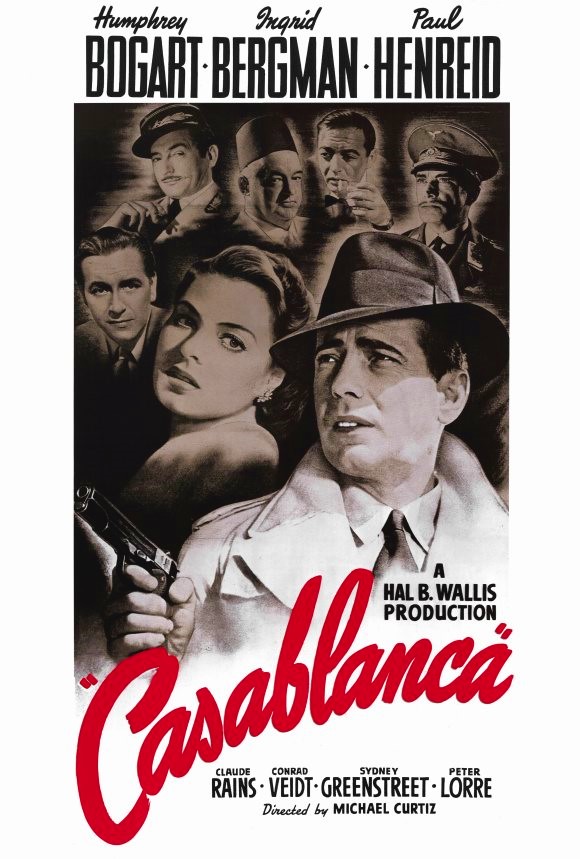

The French-Jewish anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss joined other French writers in America: Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, André Maurois and Jules Romains. Lévi-Strauss described “lives hanging by slender threads in Marseilles, where the talent and expertise of Paris in the days of her prime were reduced to the hunted, terribly tired men at the limit of their nervous resources.” The brilliant propaganda film Casablanca (1942), substituting Morocco for the escape route in Marseilles, gives a rather light-hearted view of the desperate refugees, though Peter Lorre is murdered and the Vichy French police are completely corrupt. The recurrent order “Round up the usual suspects” is more than a satirical joke: it is, rather, a dark allusion to the round-ups of the Jews. Bogart plays a Varian Fry kind of hero by rescuing the Underground leader Paul Henreid and his wife Ingrid Bergman (whom Bogart loves and surrenders), as well as the young Bulgarian woman who’s willing to sleep with the police chief (Claude Rains) in order to save herself and her husband. Unlike the thousands of people who were captured and executed or deported to death camps, the refugees in Casablanca are saved by political commitment and personal sacrifice.

The German exiles— among them Heinrich Mann, Bertolt Brecht, Franz Werfel and Arnold Schoenberg—mostly joined Thomas Mann in Los Angeles; the French artists, led by Breton, settled in and around New York. The French word for expatriation, dépaysement, literally means being outside your own country, but also suggests geographical exile and psychological disorientation. After mortal danger in Europe, the artists felt tremendous relief in reaching the sanctuary of America, but they had to transplant a whole culture from one continent to another and establish a new existence in a new country.

The New School in New York hired many distinguished exiles, and since most of the teachers and students were refugees, broken English became the lingua franca. The artists were inspired by New York’s fast pace, towering skyscrapers, jazz music and diverse population in many distinct neighborhoods, yet still tried to maintain their old ties. Ernst and Peggy Guggenheim often had delicious French dinners cooked by Marthe, the wife of Ozenfant, and Peggy bought one of his Purist paintings. She recalled that Léger, who’d walked throughout Manhattan and knew every inch of it, became their guide and took the artists to foreign restaurants in every quarter of the city. Alfred Barr, director of the Museum of Modern Art, could talk to Léger about the meaning of his work, and pay Mondrian $30 to restore his 1925 painting Composition, which the architect Philip Johnson had given to the Museum.

II

Of the fourteen painters who reassembled and appeared in the 1942 “Artists in Exile” exhibition in the Manhattan gallery of Pierre Matisse (son of the artist), Chagall, Dalí and Ernst are the most significant. Chagall (1887-1985) was born in Vitebsk, Russia, 300 miles west of Moscow, and moved to Paris in 1923. The “Phony War,” the winter suspension of battle in the West from October 1939 to May 1940, gave Chagall a false sense of security. He was in southern France when the Nazis conquered Belgium and the Netherlands, and marched into Paris in June 1940. He did not realize he was in mortal danger until Vichy, under pressure from the Nazis, adopted anti-Jewish laws in October 1940.

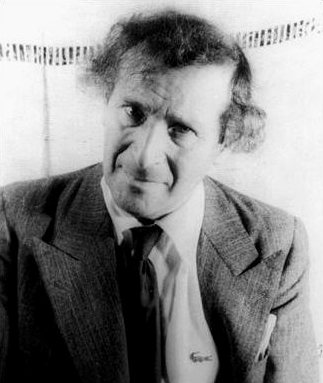

In April 1941, during a roundup of Jews, Chagall was arrested in Marseilles but freed by Varian Fry. He then nervously asked Fry: “Will I have a subject in America? Will I be able to paint?” Chagall and his wife Bella left Marseilles by train, crossed into Spain, stopped in Madrid, arrived in Lisbon in May and waited a month for the boat to New York. In September Ida, their only child, and her husband followed them via Cuba to America. Chagall spoke Yiddish, Russian and French but did not know English. When he later made drawings of what he wanted his housekeeper to do, she still could not understand him. As a Jew he’d been in far greater danger than the gentile artists, but his letter to Parisian painters in late 1944 was apologetic, defensive and guilty: “I suffered for having to leave you during that terrible year. It was not my destiny to sacrifice my life in Paris. The enemy was preparing a degrading death for me somewhere in Poland. I took the hospitable hand offered by America.”

Marc Chagall in 1941

Chagall’s art, which preserved his Jewish heritage and idealised memories of his peaceful Jewish village—when they were not threatened by pogroms—was successful in America. His bright colors, levitating oxen and horses; his nostalgic, sentimental and naïve portrayal of the work, music, lovers, weddings, and births; even his bearded rabbis and crucified Christs wearing a tallis were more appealing to the public than the puzzling work of the Surrealists. Pierre Matisse, who’d shipped many of Chagall’s works out of France, held a “Chagall Retrospective 1910-1914” in November 1941, then had an annual show of his work until 1947, and gave him a monthly income, rising from $350 a month in 1941 (about $7,500 today) to $700 six years later.

Chagall lived at 4 East 74 Street; was close friends with Mondrian and Breton; visited all the galleries and museums; and loved the Jewish neighborhood on the Lower East Side, where he could see familiar faces, eat traditional food, speak Yiddish and read the local newspapers. Chagall described America as a country of “startling vitality, novelty and size,” and was impressed by the “natural environment, by the vibrant sensibility of the people and especially by the skyscrapers.” In the spring l942 he designed the sets and costumes for New York City Ballet’s performance of Aleko, with a libretto by Pushkin, music by Tchaikovsky and choreography by Léonide Massine.

In a wartime speech to a Jewish organization, he was outraged by the European passivity, even active collaboration, when Jews were being massacred and gentiles betrayed their beliefs: “Hitler thought that when he started slaughtering the Jews, we would all in our grief suddenly raise the greatest prophetic scream, and would be joined by the Christian humanists. But, after two thousand years of ‘Christianity’ in the world, with few exceptions their hearts are silent. I see the artists in Christian nations sit still—who has heard them speak up? They are not worried about themselves, and our Jewish life doesn’t concern them.” In his major painting The War (1943), writes Jonathan Wilson, “flames engulf the city and the sky above it, and rise terrifyingly from the burning red hair of a nursing mother; a corpse lies in the otherwise deserted street, arms outstretched. Elsewhere, soldiers march, a Jewish refugee flees, and a struggling horse with a rooster on his back tries to lift an earthbound, red-wheeled cart and transform it by a dream of escape into Elijah’s flaming chariot heading skyward.”

Marc Chagall, ‘The War’, 1943

Bella Chagall continued to mourn for Russia as well as for France and said, “My parents’ house no longer exists. Everything, everyone is dead or gone.” Like Moses in the wilderness, she never failed to mention the absence of Jews when they lived in rural towns: “Here the only Jews are God Himself and . . . us.” In upstate New York, when Bella got a viral infection, newly discovered penicillin was not yet available for civilians. She fell into a coma and died on September 2, 1944. Chagall was shattered, grieved for months and couldn’t paint.

When Germany was defeated and the war ended, Chagall remembered his dead wife and her posthumous hopes, and was naively optimistic about the future: “In recent years I have felt unhappy that I couldn’t be with you, my friends. My enemy forced me to take the road of exile. On that tragic road, I lost my wife, the companion of my life, the woman who was my inspiration. I want to say to my friends in France that she joins me in this greeting, she who loved France and French art so faithfully. Her last joy was the liberation of Paris. Now, when Paris is liberated, when the art of France is resurrected, the whole world will, once and for all, be free of the satanic enemies who wanted to annihilate not just the body but also the soul—the soul, without which there is no life, no artistic creativity.”

In the summer 1945 Virginia Haggard became his housekeeper, and soon after his lover. Born in 1915, aged 30, she was a year older than his daughter Ida. Virginia was a very tall thin woman, erect in her bearing, with a long face, long brown hair neatly cut and fringed, and a hesitant look. She had a patrician English background: the great-niece of the writer Rider Haggard and the daughter of Sir Godfrey Haggard, a British diplomat who’d been consul general in Paris, where Virginia had studied art and learned to speak fluent French. Chagall’s biographer Jackie Wullschlager notes, “a sexual adventure with a young goyish woman 28 years his junior, who towered over him and whose origins, values and belief systems were completely different, was excitingly unfamiliar.”

Virginia Haggard, April 1949

Virginia was separated from John McNeil, a failed Scottish painter who suffered from depression and was unable to work, and had a five-year-old daughter, Jean. Chagall’s biographer adds, “For her, the choice was between a miserable bully of a husband who had crushed her spirit and with whom, she claimed, she had not slept for five years, and one of the world’s most famous, charismatic painters, in the affluent setting of Riverside Drive. It was no contest.” Virginia accepted her role as secret companion, living in the shadow of Bella’s memory, while Ida ran her father’s business and social affairs. Virginia lived with Chagall for seven years. He went to Europe in May 1946, and missed both the birth of his son David and the early months of his life.

In April 1946 Chagall had a major retrospective at the MOMA and the Chicago Art Institute. But as America moved toward abstraction, his art ran against the current of contemporary taste. In August 1948 Chagall and Virginia sailed from New York to Le Havre.

III

Salvador Dalí (1904-89) was already successful and well known in America before the war. Stimulated by his wife, Gala, the ex-wife of Paul Eluard, he was extremely effective in using the media to publicise his bizarre persona and his provocative art. In 1939 he designed two shop window displays for the Bonwit Teller department store on Fifth Avenue. When the owners disliked it and changed it without his permission, the furious Dalí broke the large plate-glass window, was arrested, confined to a cell full of drunks, and became a popular hero for defending his art.

When the Spanish fascists won the Civil War in 1939, Dalí changed his political views and moved from radical Left to Francoist Right so he could return to live in Spain. In June 1940 he and Gala drove to Bordeaux and crossed into Spain at Hendaye two days before the border was closed. Dalí went to Madrid to get a visa for Portugal. Gala went to Lisbon, a city filled with exiled monarchs and aristocratic refugees, to buy their boat tickets. They sailed for New York on August 8, stayed first at St Regis Hotel, then at the estate of the patron of the arts Caresse Crosby, Hampton Manor in Virginia, from August l940 to April 1941. His biographer Meredith Etherington-Smith describes his situation at that time: “He was a Catalan without a homeland, married to a Russian, living in a country he despised. . . . They were frightened, far from home, short of money, with nowhere else to go, and trying to work in completely strange surroundings.”

The arrogant Gala assumed that all the people at Hampton Manor were there to serve Dalí, the great genius. She alienated everyone by reserving the library for his work and telling them to speak only Spanish. Henry Miller and Anaïs Nin, who spoke Catalan, were also in residence, and Miller cursed the Dalís for “attempting to manage everyone’s lives and acting like a couple of shrewd bedbugs.” Meanwhile, Dalí wrote his autobiography, The Secret Life of Salvador Dali (1942). George Orwell found it disgusting and exclaimed, “if it were possible for a book to give a physical stink off its pages, this one would.”

The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí, 1942, Dover Publications

In Los Angeles Dalí painted a portrait of Mrs Jack Warner, and tried to persuade Bette Davis to make a film with him. On the way back to the East coast, they had an unhappy meeting with Frieda Lawrence, the widow of DH Lawrence, in Taos, New Mexico, where Gala was especially rude to the unfashionably dressed former German baroness. They returned to Hampton Manor for three more months, where he spent days furnishing a ruined and empty house and arranging a fantastic dinner party in the local cemetery.

The gallery owner Julien Levy feared Dalí would “go off the deep end of nonseriousness.” But his 1941 exhibitions in New York, Chicago and Los Angeles received universal acclaim. Dalí then wrote the libretto, designed the scenery and costumes for the ballet Labyrinth, with music from Schubert’s Seventh Symphony, which the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo successfully performed at the Metropolitan Opera in New York.

From 1941 to 1949 Dalí and Gala spent spring and autumn in New York, summer and winter at the Del Monte Lodge near Monterey, California, and were given special celebrity rates at the hotel. At Del Monte he arranged a “Surrealist Night in the Forest Ball,” with a wish list that included thousands of pine trees, gunny sacks and old newspapers; truckloads of fruit, store-window mannequins, animal heads; a wrecked automobile, the largest bed in Hollywood and a baby tiger. The Ball attracted many Hollywood stars, including Clark Gable, Bob Hope, Bing Crosby and Ginger Rogers.

Dalí was by now estranged from his fellow artists in America, but had his first retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in November 1941. He was still the greatest Surrealist draughtsman and had the weirdest imagination. His titles included Family of Marsupial Centaurs, Honey is Sweeter Than Blood, Mannequin Rotting in a Taxicab and, for colour contrast, Impact of Seven Negroes, a Piano and Ten Black Pigs on the Snow. His recurrent motifs were cruelly arranged crutches, skulls, lobsters, ants and melted watches. In April 1943 he successfully exhibited his “American Portraits” at the Knoedler Gallery in New York.

In 1944, when interest in avant-garde art was falling, Julien Levy closed his gallery. Dalí joined George Keller’s gallery, but after 1948 he hired a gallery for his own exhibitions, and dealt directly with museums and important collectors. In 1944 he also ventured into movies and created dream sequences, “very solid and very sharp with long perspectives and black shadows,” for Alfred Hitchcock’s Spellbound. Since neither Dali nor Hitchcock liked them, the scenes were eventually eliminated.

Dalí’s marriage to Gala, a modern version of Messalina and Lucrezia Borgia, was a personal though not a professional disaster. Elena Diakonova (1894-1982), called Gala, was born in Kazan, Russia, the daughter of a high-ranking official. She’d met Paul Eluard in a tuberculosis sanatorium in Davos, Switzerland, married him in 1917 and had a daughter, Cécile, in 1918. From 1922 to 1927 she had an affair with Max Ernst, a transitional lover between her two husbands. She lived with Dalí beginning in 1929, married him in 1934 and cynically told the artist Roland Penrose, “Didn’t I do well to ditch Max Ernst: he’s a loser. But as for Dalí, just look at the success he’s become since I took over.”

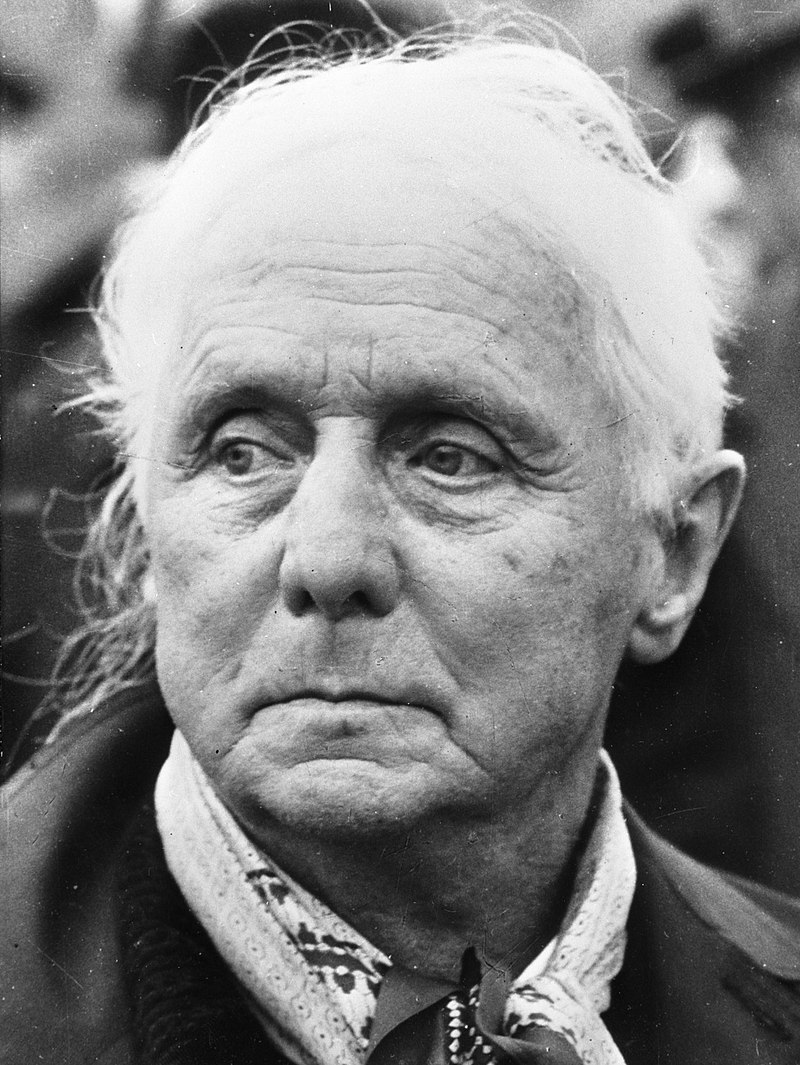

Salvador & Gala Dalí

Gala, like Peggy, was egoistic, manipulative, domineering, sexually voracious and extremely unpleasant. Gala was attractive and poor; Peggy homely and rich. Both were self-appointed and successful art entrepreneurs. Gala, keen on diversity in her lovers, was a self-confessed nymphomaniac. She could never have sexual relations with the voyeur Dalí, who encouraged her to enjoy compensatory sex with young men while he watched and masturbated. Gala was like Blazes Boylan in Joyce’s Ulysses, who told the husband Leopold Bloom, “You can apply your eye to the keyhole and play with yourself while I just go through her a few times.” She also asked Max Ernst’s young son, Jimmy, if he’d like to have sex with her. When he declined the offer she attacked him with a torrent of abuse. Finally, there were no more sex fantasies, and Gala became Dalí’s mother and jailer. She drove up and down the California coast in her huge Cadillac, plotted how to get more money out of him and kept him a virtual painting prisoner. He was there to work and make her rich so that Gala could pursue her insatiable appetite for sex and her desire to preserve her youth.

Ruth Brandon perceptively noted, “Dalí, with his customary acuteness, had seen that to render himself acceptable to the American market he must scuff off all the shackles of theory or principle. All that mattered was the product. And that product was, first of all, Dalí himself: a monstrous and outraged joke which he called Surrealism. . . . Dalí performed the universal service of opening up the public imagination to modern art in general and Surrealism in particular.” His mission accomplished, in 1948 he and Gala returned to Spain.

IV

Max Ernst (1891-1976) came from a Catholic family near Cologne in the

Max Ernst

Rhineland. He studied literature, philosophy, art history and psychology at the University of Bonn. In 1914-18 he served in the German army and first joined a field artillery unit, marking positions on maps and painting for the rest of the day. After a period of light duty on the western front, he was sent with the Prussian Death’s Head Hussars to swampy Poland, with headquarters in Danzig. Commissioned a lieutenant, he was sacrificially posted to the most dangerous areas so that the officers of his elite regiment would survive after the war. He was wounded twice: once from the recoil of a gun, then from the kick of a mule.

Little is known about the details of Ernst’s wartime experiences, which were similar to those described by Erich Maria Remarque in All Quiet on the Western Front (1929). His duties involved trench maintenance, constructing dug-outs and laying barbed wire in rear positions. He toiled day and night, doing difficult and dangerous work while constantly under long-range artillery fire. Remarque emphasized the truly horrific conditions at the front. The soldiers ate rotten food and suffered from constant hunger, intense cold and clinging mud, tormenting lice and ravenous rats, suffocating gas and searing flamethrowers, endless artillery and aerial bombardment, shell-shock and insanity, excruciating wounds and barbaric surgeons. They lived with the threat of death and accepted the fragility of life.

Like many of the artists, the handsome blond and blue eyed Ernst was inspired by several wives and many lovers. Both the paintings and the painter were well and truly hung. From 1918 to 1921 he was married to the German museum curator Luise Strauss, and in 1920 they had a son, Jimmy. In 1922 he became the lover of the Russian Gala, then married to his close friend Paul Eluard, and they formed a companionable ménage á trois. In 1924 Eluard stole money from his wealthy father and suddenly disappeared. He sailed from Marseilles through the Atlantic Ocean, the Panama Canal and the Pacific Ocean to Saigon. When he reached the Canal he sent a letter to Gala asking her to follow him and hoping she “will pass this way soon.” Ernst and Gala followed her elusive husband by a different route — through the Mediterranean, the Suez Canal and the Indian Ocean — and they met him in French Indochina. Eluard justified his role as a complaisant cuckold by confessing that “he loved Max more than he loved Gala.” Ernst also visited the then little-known Khmer ruins at Angkor Wat in Cambodia, which had a powerful influence on his art.

In 1927 Ernst met the French teenager Marie-Berthe Aurenche and was married to her until 1937. During this time he worked with Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí on the cruel Surrealistic film Un Chien Andalou (1929), including the slitting of an eyeball and a dead donkey on the piano (which influenced the dead horse in the producer’s bed in The Godfather), and on the satirical comedy L’Age d’Or (1930). From 1932 to 1936 Ernst lived with the Argentine-Italian painter Leonor Fini, though (she said) “he was always involved with four or five women at the same time.”

From 1937 to 1939 Ernst lived with the wealthy upper-class English painter Leonora Carrington. When World War Two broke out in September 1939 the anti-Nazi Ernst was interned by the French as an enemy alien; after the conquest of France he was interned by the Gestapo; and he escaped both times. While he was in prison, Carrington gave their house near Avignon to a French friend to save it from the Germans. She then suffered a mental breakdown, and finally managed to leave for Portugal.

Unlike most of the émigrés, Ernst could speak English. His work had been in the Dada and Surrealism show at the Museum of Modern Art in 1936, and he had useful contacts in America. Helped in Marseilles by his son Jimmy and by Alfred Barr at the Museum, he crossed into Spain with his patron and lover Peggy Guggenheim. At the Spanish border he showed his pictures to an appreciative and sympathetic guard, who told him: “Monsieur, I adore talent. You have a great talent. But I must send you back to Pau. There is the train for Pau. Here on the left is the train for Madrid. Here is your passport. Don’t take the wrong train.”

In Lisbon, Guggenheim’s biographer writes, “Max told Peggy that he had just found Leonora Carrington and that she was about to marry a Mexican to ensure passage out of Europe. Max was obsessed with her, and Leonora wavered between going back to him or marrying her Mexican suitor.” In the end Leonora chose the Mexican, and Ernst flew to America with Peggy and her entourage on a luxurious Pan American Clipper. But his troubles were not yet over. He was again detained as an enemy alien and spent several days on Ellis Island until freed through the efforts of Peggy and the gallery owner Julien Levy. Soon after his release he was interrogated on Cape Cod and in Boston by suspicious agents of the FBI.

In Paris the artists had met frequently and informally in their favorite cafés. In New York they were spread throughout the city and in the suburbs of Long Island and Connecticut. Ernst complained that spontaneous encounters were lost: “You had to phone and make an appointment in advance. The pleasure of a meeting wore off before it took place. As a result, in New York we had artists, but no art.” But they didn’t try to recreate the atmosphere they missed by encouraging a wealthy patron to subsidise an artists’ café. In 1942 Ernst also told a French friend that his tastes did not match those of the Americans: “You have no idea of the intellectual famine that exists even in a ‘centre intellectuel’ like New York. It’s almost impossible, for example, to find some recent books.”

In 1941, recalling his two arrests, internments and escapes, as well as his detainment and interrogations in America, he told the English painter and patron Roland Penrose, “I didn’t have too much difficulty in adjusting myself to this new life, after all the catastrophes and misery I lived through in France.” In March 1942 he had his first New York show with Curt Valentin, a Jewish art dealer who’d escaped from Berlin, which went on to Chicago and New Orleans. But there were no sales and the shows failed. In June 1942, with André Breton and Marcel Duchamp, he founded the Surrealist magazine, experimental in format, VVV; in April,1943 his painting appeared on the cover of a special issue devoted to him.

Ernst had no money except for the pictures he sold to Peggy, who was “crazy about” his work. Supported by Peggy, he was much better off than most of the other émigrés. His attraction, her biographer writes, was based on a safe passage from Europe, a steady outlet for his work, a way to make excellent connections and financial security. When Alfred Barr traded a Kazimir Malevich for an Ernst, Peggy tactfully paid Ernst, though no money was involved in the exchange. His overbearing benefactor, however, disliked the idea of living in sin with an enemy alien and insisted on a wedding. He finally caved in to her demands, and in 1941 they began a contentious and short-lived marriage. John Russell observed, “Outwardly his situation was highly advantageous: the splendid studio overlooking the East River, the marriage to a prominent figure in the New York art world, the freedom from the petty discomforts and humiliations which awaited other refugees from Europe.”

There were inevitable quarrels between Ernst and Peggy, Peggy and her fifteen-year-old daughter Pegeen, and an undercurrent of sexual interest between the pretty adolescent and her stepfather. Peggy had an unfortunate putty-shaped blob of a nose, but she felt attached to it and never got it fixed. Ernst was not attracted to her, didn’t even like her, and had no interest in satisfying her. She was wounded by his remoteness, and unwisely complained that the great ladies’ man was “cold as a snake” and “made love badly.” A friend remarked, “Ernst is the easiest and most delightful of companions, but there is no mistaking the inheritance of taciturnity and stern withdrawal on which he can draw when the occasion demands it.” When Peggy insisted that he paint her, she appeared in his art as a monster.

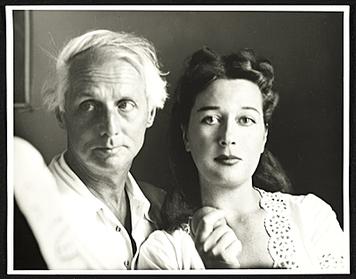

In 1942 Ernst met the beautiful American Surrealist painter Dorothea Tanning, nineteen years his junior. Peggy agreed to sacrifice her current lover, Marcel Duchamp, if he would give up Dorothea—an extremely unappealing offer. Dorothea sealed the bargain by appearing at a gallery opening wearing a ravishing Surrealist costume with see-through portholes that revealed photos of Ernst. As love triumphed over lucre, he left Peggy in May 1943; when his divorce came through three years later, he married Dorothea. Also keen on all-inclusive diversity, his wives and lovers were a mélange of German, Russian, French, Argentine-Italian, English and American.

By Robert Bruce Inverarity, photographer – Max Ernst and Dorothea Tanning, ca. 1948, in the Archives of American Art, Fair

In 1946 Ernst and Dorothea moved to Sedona, a desert town near Flagstaff in central Arizona, where he built and decorated a house. Russell writes that it “offered isolation, a celestial climate, a way of life that was both economical and free from suburban constraints. It was deeply moving for him to come upon a landscape which had precisely the visionary quality that he sought for on canvas.”

In 1945 his exhibition at the Levy Gallery had been criticized as “perverse, unhealthy and abnormal.” There were no sales, and he reported his humiliating rejection: “My show in New York didn’t go well enough for the demands of Mr. Julien Levy so he’s letting me go.” His 1949 show in Beverley Hills was another a financial disaster. Werner Spies notes that in 1946 “Max and Dorothea endured a tough time following Max’s acrimonious split from Peggy Guggenheim in New York, and had come to Arizona to build a new life. Max’s sales had practically dried up” and Peggy no longer supported him. “He would set off on long journeys in his car towing a trailer loaded with paintings wrapped in blankets and return without one sold.” The traveling art peddler, Willy Loman in the desert, had a hopeless task in Arizona.

The Surrealists rebelled against the society that had rushed blindly into the insane slaughter of World War One. One of the most powerful paintings of World War Two, created in America, was André Masson’s Oradour (1944). In revenge against the French Resistance, on June 10, 1944 the Germans had completely destroyed this little French town and massacred the entire population. Masson portrayed his outrage in a hunched-over black figure with a skull-like head surrounded by fiery destruction.

Ernst’s great painting, Europe After the Rain II (1940-42), an allegory of the annihilation of Europe in a rain of fire, expresses his feelings of horror and complete devastation. A helmeted, bird-headed soldier (as in Hieronymus Bosch), wearing a furry-feathered cloak and holding a spear with fluttering pennants, threatens a harmless green woman. His horned head and hooves emerge from an apocalyptic war-ravaged landscape with jagged pillars, jungle-covered ruins and what seem to be dead men’s bones. The woman turns away from him and from the canopy that has collapsed and buried the bull that has tried to abduct Europa.

Europe after the Rain II, by Max Ernst,

c.1941; United States. Oil on canvas

Desmond Morris writes that Dorothea, “painting with academic precision, created a sinister world of bleak hotel rooms, corridors and landings where young girls interacted in odd ways with monsters, dogs or other strange beings.” He claims that “her painting style was never influenced by that of her charismatic husband,” but on the previous page he reproduces her painting Birthday (1942), whose green tangled vines from the woman’s waist to her feet are similar to the weird foliage in Ernst’s Europe After the Rain II.

In 1949, after eight stimulating and convulsive years in America, Ernst and Dorothea sailed from New Orleans via Havana to Amsterdam. He settled down with her, they remained married for the rest of his life, and she lived to the astounding age of 102.

V

None of the artists had expected his exile to last beyond the war years. Chagall, Dalí and Ernst—like the writers Mann, Nabokov, Huxley and Milosz—finally left America and returned to Europe. Dorothea Tanning shrewdly observed, “after the war they went back to where they came from, leaving the key in the door.” The Surrealists set out to shock the Americans and found them very shockable. Freud’s theories of the power of the unconscious had influenced the Surrealists, and psychoanalysis had become fashionable in New York. The avant-garde—sanitised, widely disseminated and avidly consumed by the American public—had survived the war by infiltrating New York.

In 1946 Matisse sadly told Picasso, while “poring over American catalogues of Jackson Pollock and Robert Motherwell, ‘And in a generation or two, who among the painters will still carry a part of us in his heart, as we do Manet and Cézanne?’ ” In fact, the exiled artists had a profound influence on American painters. Ernst, for example, showed Pollock how to drip paint onto a flat canvas. The artists also had personal contact with Motherwell and Robert Rauschenberg who, after the realism of the 1930s, were ready to launch Abstract Expressionism. Willem de Kooning (born in Holland) and Mark Rothko (born in Latvia) were also receptive to the French painters. World War Two drained Europe and energised America, greatly enhanced the public and private collections of modern paintings, and shifted the center of the art world from Paris to New York.

Jeffrey Meyers, FRSL, has published Painting and the Novel, The Enemy: A Biography of Wyndham Lewis, Impressionist Quartet, Modigliani: A Life and Alex Colville: The Mystery of the Real. His book on his writer-friend James Salter will be out in spring 2024.

A Message from TheArticle

We are the only publication that’s committed to covering every angle. We have an important contribution to make, one that’s needed now more than ever, and we need your help to continue publishing throughout these hard economic times. So please, make a donation.