When Germaine Greer wrote a study of female artists she called it The Obstacle Race. To achieve success, she argued, women had to overcome the career equivalent of rope ladders and monkey bars. For centuries, for instance, they were banned from live art classes, where they would have gazed on male flesh.

The trouble was that the most respected art form was historical paintings, which often involved semi-naked men flexing their muscles heroically. So how were women supposed to pull these off when they weren’t allowed to practise?

The Swiss painter Angelica Kauffman — the subject of a huge solo show at the Royal Academy, opening this week — is a rare example of one who army-crawled her way to recognition and beyond. Thanks to her smart business acumen, her flair for colour and her eye for harmonious composition, which led some to hail her as “the female Raphael”, she rose to become the most successful European artist of the late 18th century.

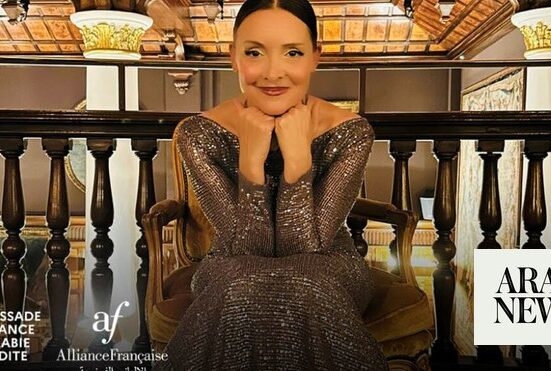

Self-portrait with Bust of Minerva, c 1780

ANGELICA KAUFFMAN, GRISONS MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS

And this despite facing an early obstacle of staggering malignity, which threatened to derail her career completely. On the cusp of breaking through, Kauffman was taken in by a conman calling himself Count Frederick de Horn, who tried to steal her money, separate her from her friends, ruin her reputation and spirit her out of the country where she had made her home.

Born in the city of Chur in Switzerland, she had been taught to paint by her father, Joseph, who was also an artist. The girl soon outstripped the man and was hailed as a prodigy. Travelling in Italy, she cannily painted the rich and famous: the actor David Garrick, the art critic Johann Winckelmann.

Her subtle portraits convey a living sense of their subjects across the ages. In her picture of Garrick, for instance, the face is serene. Yet the way his fists grip the ear and top bar of his wooden chair, as he turns to the viewer, who regards him from behind, suggests an awareness of how precarious his position is at the top of his profession, and how tightly he has to hold on.

• Lurid, limp, inert — why Flaming June makes our art critic see red

The same went for Kauffman. When she came to London in 1766 aged 25, she immediately sought out Joshua Reynolds, who was one of the best-respected painters in the country. The two artists got on famously and agreed to paint each other. Soon she earned a commission to paint the English queen herself. “Everything was going her way,” says Annette Wickham, co-curator of the RA show. Everything, that is, until she met the mountebank.

Travelling everywhere in a carriage attended by footmen wearing splendid green livery, he cut a glamorous figure. A dramatic one too. He was the victim of persecution in his native Sweden, he told Kauffman. His enemies falsely accused him of conspiring against the Swedish king. Wherever he went, he carried a phial of poison in his coat.

One day, he turned up in a terrible state at her home in Golden Square, Soho. Pale and trembling, the count declared that he was about to be extradited and threw himself on her mercy. “There is not a moment to lose,” he said. “Either you make me your husband at once, or I am a lost man.” What else could Kauffman do? Reader, she married him.

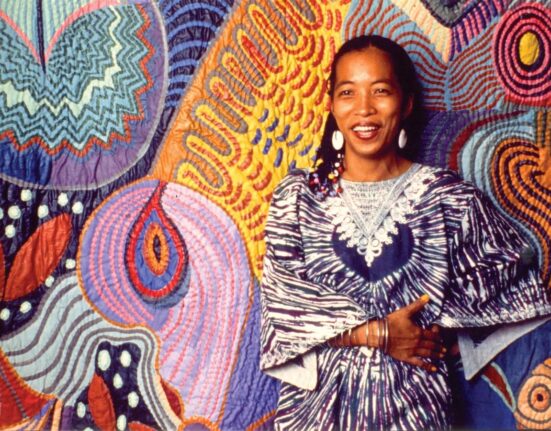

Portraits of Domenica Morghen and Maddalena Volpato as Muses of Tragedy and Comedy, 1791

© COLLECTION OF NATIONAL MUSEUM IN WARSAW. PHOTO: PIOTR LIGIER/ANGELICA KAUFFMAN, ROYAL ACADEMY OF ARTS

The knot was tied at St James’s Church in Piccadilly in September 1767. Yet soon enough, problems began to surface. Sex was off the cards, it was rumoured. A wound during military service had left de Horn de-horned. He quarrelled with her concerned father and forbade her friends from visiting her. Then — fantastically — the real Count Frederick de Horn arrived in London and presented himself at court.

The authentic nobleman was astonished to be congratulated on his recent marriage to a talented artist. He knew nothing of the matter, he insisted. And so the truth — or versions of it — began to come out. The charlatan was a servant of his, or an illegitimate son, or both, who had stolen documents of his and moved to another country, where he could carry out his imposture. He was a serial fraudster. He was already married. His union with Kauffman was bigamy.

Sensing that the game was up, the artist’s mythomaniac husband moved fast, demanding £500 as the price for leaving her alone. When she refused, he tried to kidnap her with the help of hired thugs. In the end, Kauffman coughed up. She paid him the reduced sum of £300 (the equivalent of about £40,000 today) to quit the country and never contact her again. These things the charlatan did.

The mystery remains. How did Kauffman, so clued up in other ways, let herself be duped? Either the false count was very good at his game or else, as Greer argued, Kauffman was fed up of being the subject of salacious rumours.

At various times she was rumoured to have had affairs with Reynolds, the painters Nathaniel Dance and Henry Fuseli, and even the French revolutionary Jean-Paul Marat. “She was a sex object,” Greer. said. “They kept trying to talk about who she went to bed with so she couldn’t be taken seriously.” She married de Horn “to get away from the gossip”.

Given the sketchiness of the sources and this distance of time it’s hard now to establish what really happened in 1767. Whatever the truth, she somehow survived the scandal. She threw herself into her art and, by a combination of graft and skill, achieved “enormous sales figures”, in the words of Wickham’s co-curator, Bettina Baumgärtel. She earned so much money, primarily through her portraits of the rich, that Baumgärtel estimates she became Europe’s “richest bourgeois woman who became wealthy from her labour alone”.

In the 1780s Kauffman was as widely known as any contemporary artist — largely thanks to reproductions of her designs, which appeared in middle-class homes, printed on plates and snuff boxes, fans and fire screens.

Design, 1778-80

© ROYAL ACADEMY OF ARTS, LONDON. PHOTO: JOHN HAMMOND

An engraver declared in 1781, “The whole world is Angelica-mad.” She was also respected by the majority of her fellow artists. When the RA was founded in 1768 Kauffman was one of only two women included among the 40 academicians. The fact that she was commissioned to paint four allegorical works for its premises (to this day they adorn the RA’s entrance at Burlington House) is proof of her high standing.

In later life she moved to Rome, where she befriended Goethe and held court at her artistic salon. Meanwhile, she cemented her reputation for historical paintings, and her choice of subject matter shows a preference for women who took control of their lives and became the heroines of their own stories.

She was an example of this herself. When she remarried, embarking on a second marriage with the artist Antonio Zucchi, she insisted on a prenup. Highly unusual at the time, this ensured she retained control of her earnings.

Kauffman died in 1807 at the age of 66. The sculptor Antonia Canova led the funeral procession through the streets of Rome to the church. As had happened at the funeral of Raphael, two examples of her work were carried in triumph.

Soon afterwards, a bust of Kauffman was placed in the august surroundings of the Pantheon, next to the bust of Raphael himself. A detailed account of the funeral was read aloud at a council of the RA in London. Its contents were transcribed in full in the minutes of the meeting. It was a mark of the great respect in which Kauffman was still held by the RA after so many years.

Yet, as Baumgärtel observes in the catalogue for the RA show, it is striking that Kauffman “has had to wait more than 250 years for a solo exhibition celebrating her work at the Royal Academy, despite her being one of the founding members of the institution”. For Kauffman, even after death, the obstacle race continued.

Angelica Kauffman is at the Royal Academy from March 1 to June 30