The artist and filmmaker John Akomfrah has vivid memories of the coup that ousted Kwame Nkrumah in Ghana in 1966, when he was eight. His pan-Africanist father was an Nkrumah loyalist who “died in the upheaval”, he says. “My whole life changed — the innocence went.”

Now 66, the Royal Academician, who was knighted this year and chosen to represent Britain at the 60th Venice Biennale next spring, returns repeatedly in our conversation to the end of innocence. When he arrived in Britain with his mother and brothers the shock was repeated, as what was “paradise compared to where we’d been” gradually revealed its “complexities”.

These complexities were explored by the Black Audio Film Collective he co-founded in 1982, whose first film, “Handsworth Songs” (1986), mirrored the 1985 uprisings in Birmingham and London with a montage of archive footage, newsreel and stills that remains part of his signature style. Co-founder of the production company Smoking Dogs Films in 1998, Akomfrah makes cinema and TV films as well as multichannel art installations such as “Vertigo Sea” (2015), splicing the greed and bloodshed of whale harpooning with images of transatlantic enslavement and modern migration, or “Mimesis: African Soldier” (2018), memorialising forgotten Africans on the first world war’s western front. In a growing body of work on climate disaster, “Purple” (2017), a six-channel meditation on the impact of human progress on wildernesses (showing at the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington DC until January) is named after the colour of mourning in Ghana.

The loss of innocence, the voyager’s idealism and the despoiling of paradise are all themes in his latest work, “Arcadia” (2023), a poetic, multi-layered film installation about the cataclysmic birth of the modern age in the first wave of globalisation. A re-edited version of a work first shown at the Sharjah Biennial (now with more signposting and song), the five-channel, 50-minute piece has its UK premiere at The Box in Plymouth from November 30, as part of a season on Revisiting History. It coincides with John Akomfrah: A Space of Empathy, the artist’s first major survey in Germany, now at the Schirn Kunsthalle in Frankfurt.

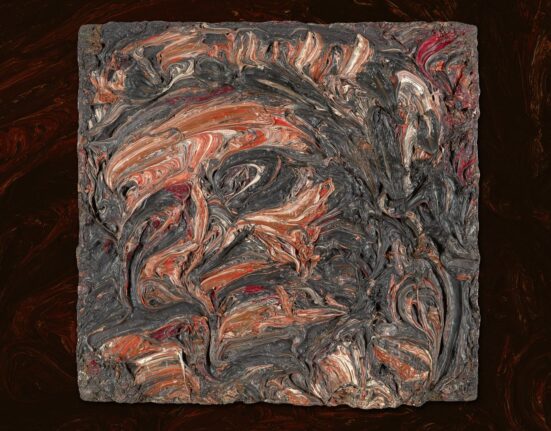

Across five screens in the shape of a cross, “Arcadia” is a meditation on the advent of European settlers in the so-called New World: the peoples, land, flora and fauna they encountered, and the global implications for a planet on the cusp of the Anthropocene.

Edenic scenes and seascapes, filled with natural wonders from northern lights to fireflies, are cut with images of ships and cargo — precious metals, peppers, potatoes. Along with actors and props — from conquistador portraits to grandfather clocks — are magnified shots of variola: the smallpox virus.

Akomfrah was working on a commission about the Mayflower, four centuries after it sailed from Plymouth in 1620, when lockdown struck. The Covid pandemic crystallised his disquiet. “Something didn’t make sense,” Akomfrah recalls when we meet at the Lisson Gallery in London. “Why was there so little resistance to the Pilgrims? We were coming to it too late, missing a significant chapter of plague and pestilence.” In the century or so after Columbus, as European invaders brought diseases to which there was no immunity, and fought those who survived the epidemics, “almost 60mn people died”.

Covid, with its disproportionate impact on black communities, brought home to him the role of “non-human agents” in history. Arcadia includes images of smallpox sufferers, “people struggling to understand what’s going on”. The work’s crucifix form, “like a portal”, signals the centrality of religion. “By the time Europeans arrived in Mexico and Colombia, they understood they were harbingers” of disease and death, but it was “seen in terms of divine providence”.

The Mayflower, he says, was the “second act of the Columbian Exchange” — the massive transfer of populations, goods and much else between Europe and the Americas from the 15th century. “Europeans arrive in a wave of disease and conquest, destabilising the place, and take from it commodities. This completely unequal exchange had a devastating impact, but gave a major boost to the Old World. One part of the globe was impoverished, while another grew in wealth and importance.”

Archival images include the work of ships’ chroniclers, artists and engravers, as well as Inca and Aztec codices. “First-nation Americans tried to make sense of what was happening in a visual language of their own. But much remains opaque.” Woburn Abbey’s famous 1588 “Armada portrait” of Elizabeth I — on show at The Box until January 7 — is glimpsed in Arcadia, the queen’s hand resting proprietorially on a globe, challenging Spanish power in the Americas. “There’s gold everywhere, hiding in plain sight,” Akomfrah remarks of the painting. “I hadn’t seen what it was alluding to, but I’ve lost my innocence. I’ll never be able to see it without thinking of these other, tragic stories.”

While new footage was shot mainly in the UAE or Scotland, astonishing aerial and other archive film, from canyons to rainforests, is down to a partnership with the BBC Natural History Unit. For Akomfrah, this is “history in its purest form; it preserves, in the most pristine forests, what the Portuguese explorers, British pirates and Spanish conquistadors saw — what drew their breath”. His interest is partly in the “powerful drives at the heart of the colonial project”. Migration, he adds, is “primarily a utopian impulse”.

Building on Arcadia’s soundtrack of song, Nine Cantos, the working title of his installation for next year’s Venice Biennale, will, he says laconically, “be about the auditory”. The personal aesthetic he terms bricolage extends to the sonic. As he describes its origins: “Bits and pieces of my heritage and identity make up a, not seamless, whole, yet I make sense of myself. So what if I used myself, my own identity, as a model for drawing disparate sources into a narrative.” The drive is to “find a way of banishing difference, by getting fragments to agree to a momentary union. When that happens, it’s beautiful.”

His inspirations range from Turner (“one of the major unseen guests at my table”) to Russian filmmaker Tarkovsky and the Armenian Sergei Parajanov. Virginia Woolf’s novel The Waves bowled him over with its “montage; the precise juxtaposition of nature, light and flickering consciousness fascinates me.” An “immortal” presence is his friend, the late cultural theorist Stuart Hall about whom Akomfrah made the installation “The Unfinished Conversation” (2012) — on show in Frankfurt — and “The Stuart Hall Project” (2013), a film of archival footage set to a Miles Davis soundtrack.

“Five Murmurations” (2021), at the Smithsonian National Museum of African Art in Washington DC until January 2024, is his black-and-white film installation on Covid, George Floyd and Black Lives Matter. This moment “opened gates of consciousness that can’t be closed, at least for a decade,” Akomfrah says. “Something about Floyd’s death brought that on — it almost looked like a crucifixion.” Although many institutions have “walked back on promises,” he adds, “enough realised it was a turning point if they pledged to make it real”. In sum, “I don’t believe nothing has changed.”

For him, art opens up possibilities. “All people who believe in the redemptive qualities of bricolage are believers in forging unity from difference,” he says. “Deep down, I believe that people want to speak to each other. You just have to find a way.”

The Box, Plymouth, November 30-June 2, theboxplymouth.com

The Schirn Kunsthalle, Frankfurt, November 9-January 28, schirn.de/en

Smithsonian National Museum of African Art, to January, africa.si.edu

Follow FTWeekend on Instagram and X, and subscribe to our podcast Life and Art wherever you listen