A lush portrait in oil hangs at the Museum of Girodet in pictorial town of Montargis, North Central France. The museum which is dedicated to one of the most renowned painter of nineteenth century Anne Louis Girodet-Trioson (French, Montargis 1767–1824 Paris) simply referred as Girodet holds his prominent works in signature classicism, romanticism. The said canvas is titled as “Portrait of an Indian” (1807). Interestingly, the costume worn by the model is not Indian but Ottoman.

One would wonder why the artist titled the portraiture as ‘Indian’ yet adorning his model with Ottoman clothes. Was this lack of authenticity deliberate? Girodet’s work mostly had elaborate settings, depicting themes from contemporary French culture, portrayals of elites or Greco Roman mythologies, but then there were also ones with fictitious elements, a mix of imagination derived from hearsay of foreign lands.

And Girodet was not the only one, a whole generation of European intelligentsia, artists, writers, poets included these fanciful imageries in their creations which were connected to distant places and generally referred to as Orient – where ‘unknown’ people lived. In sum they were alien to western imagination and experiences.

Geographically Orient denoted Middle East, North Africa, regions on the east of Mediterranean. What was unknown created, both attraction and alienation all at once leading to studying, observing, theorising about Orient; birthing the term “Orientalism”. Orientalism all in all is a representation of a sweeping understanding of Eastern Cultures often imagined and unsubstantiated constructed through a dominant occidental lens.

It is not mere “representation of the East in Western art which blurred the line between fantasy and reality” as often curators in colonial Museums would tell you (Julia Tugwell – An Introduction to Orientalist paintings) it is aligned with how Palestinian-American writer, thinker, academic and activist Edward Said deconstructed in one of the most influential texts of our times ‘Orientalism’ (first published in 1978)“.

The Orient was almost a European invention and had been since antiquity, a place of romance, exotic beings, haunting memories and landscapes, remarkable experiences”

In Said’s words, “The Orient is not only adjacent to Europe; it is also the place of Europe’s greatest and richest and oldest colonies, the source of its civilisation and languages, its cultural contestant and one of the deepest and most recurring images of the Other”.

He explains through the book how the Orientalists or the westerners perpetuated and propagated an understanding of Asia, Middle East and North Africa that is representational of their “control over the exotic and mysterious Orient”.

The timeline for this problematical understanding was around the French emperor Napoleon invasion of Egypt. With French colonisation a swathe of travellers, officials intellectuals began visiting Egypt and parts of North Africa which until then were restricted to military campaigns and trading. What consequently was produced in art would be grounded in the settings and scenes from these countries lived or fantastical with high quotient of ‘exotic’.

Said identified “late eighteenth as a starting point” of the idea and denotes Orientalism “as the corporate institution dealing with the Orient”. He tells of the West’s self-assertion of stating about east and even authorizing views on the same.

Art, architecture, design all bore the mark of this overloaded occidental gaze, a perceived ‘western authority’ so to say, a monopolistic understanding of know all with imaginary pictorial elements, creating a new wave of ‘romanticism’.

Pertinently the earlier centuries had seen art themed read costumed portraitures appearing in Renaissance and Baroque style but they hadn’t caught such frenzy depicting the “contrasting image, idea, personality, experience” (Said, 1978) of the Other.

In reality the European artist would hardly have any access to the private quarters of the ‘Others’ read the locals. It isn’t therefore a surprise that much of Orientalist art depicts markets, vendors, public edifices, lanes and landscapes.

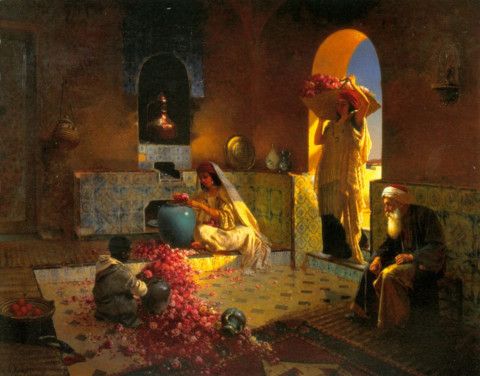

When it came to depicting interiors, it would be a mish mash of motifs, symbols taken from these cultures laced with fantasy Said remarks was never “merely imaginary” but political. It is a seminal thought that the Palestinian literary theorist, academic used to deconstruct the stereotypes and myth employed by orientalists legitimizing their views.

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons

The question lay in who is seeing – it’s the white man of course with his fantastical gaze of “distant lands” – cities that did not resemble Paris or London or Vienna in any way.

A paradigm formed through their experiences of Middle East, North Africa, India and what was then called Levant (every place on the east of Mediterranean present day West Asia) where “the otherness” was the driver, where all things “unfamiliar” had to be judged through the lens of the west – the Occident!

Post Said scholarship may have understood his brilliance yet a large percentage of public imagination even today presumes the region as places where one may end up meeting carpet sellers, potters on the roadside, bazaars full of fragrant spices and perhaps suicide bombers who believe in ideologies that are extreme and far from the projected understanding of democracies.

The last bit of these problematic understanding began circulating post 9/11 and on all times in later half of twentieth century when the West had presumed this part of the world as their “threat”! The root of this bigoted hypothesis lay in Orientalism.

Orientalism served imperial interests, grounding itself in the idea of “otherness”. It was differently posed then because the world was not globalized read Islamophobia was not invented then. In sum it was theorising distinction between west and east; western superiority and eastern inferiority.

Image Credit:

In The Canvas

The list orientalists are long spanning across century, including the prominent ones Rudolf Ernst, Jean-Léon Gérôme or popularly Gérôme, Ludwig Deutsch, Gustav Bauernfeind, Charles Robertson, Edward Weeks, Osman Hamidi Bey (1842-1910) who happened to be the only painter of Turkish origin while others were from western Europe mostly France, Austria, Italy, England, Germany and from America.

What appealed to the artists reflected on their canvas translated as watercolors, oils, sketches. Often they would be populated with recurrent themes of men crossing dessert, prayers, bazaar and its activities, with sellers, scribes, storytellers, Turkish bath spaces, harems like in Gérôme’s “Riders Crossing the Desert” (1870) or Deutsch’s “Scribe” (1904), or his very animated “The Orange Seller” (1886), Charles Robertson’s “A Carpet Seller in Cairo” and Rudof Ernst’s “Mosque of Rustom Pasha, Constantinople”.

While these depictions carried a documentary narrative, the visual elements also led to West’s early photographic and cinematographic perceptions. It isn’t surprising therefore that Hollywood films would depict Middle East or North Africa, India a certain way, invariably with stereotype elements like Bedouins, rustic looking men with turbans, remote habitation, snake charmers and belle dancers not to say and women in abaya or veils.

Image Credit:

In Gérôme’s “Riders Crossing the Dessert” the viewer can sense the harsh desert climate, while a party of men cross a desert. At the centre of the painting is a rider draped in a rust colored cloak. Invariably the veiled character becomes a point of compelling curiosity, yet it was a fictional one with no authenticity attached.

His clothes too were not the usual worn in Egypt at that point of time (a year after Suez Canal was opened). In Deutsch’s “The Orange Seller” the title strangely does not use plural nor does it hint at the gender of seller whereas the actual painting depicts more than one woman selling oranges.

For a western viewer these would leave deep impressions, leading to presumptions about the imaginary scene or evoke a sense of eternity as if at the turn of nineteenth century most Egyptian women were orange seller’s or every Egyptian would wear a cloak.

Deutsch’s said oil painting which was composed as a mid-shot also left one room to question how a bazaar may look like. Interestingly in another contemporary work depicting a large buzzing bazaar scene titled “A Carpet Seller in Cairo”, by Robertson one is curious beyond the apparent scene. In both arts the point of view of the general western audience remain same – of curiosity, to know the “imaginary” and faraway.

Of many Orientalist painters, Rudolf Ernst’s life and work were perhaps more authentic and experiential than others’. Ernst travelled across Morocco, Egypt, Istanbul finally settling for a reclusive life on the outskirts of Paris, styling his home in Ottoman ways an unusual for a westerner. The painter’s lived life did reflect his sincere connect with Middle East and North Africa.

A good example from his oeuvre would be “Mosque of Rustom Pasha, Constantinople”. Pertinently, the mosque was designed during the reign of Suleiman the Magnificent by his master architect Sinan. Ernst was somewhat truthful in his artistic depiction of the mosque’s interior with elaborate Iznik tiles, mihrab (sacred niche) and minbar (pulpit), the placement of the Ottoman candlesticks.

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Beyond this intermittent authenticity his work too bore western gaze specially when it came to depicting women who were shown mostly fair skinned as is noticeable in his much circulated “The Perfume Maker”.

Closing this discussion without mentioning Osman Hamidi Bey the only artist with eastern roots would leave it incomplete. Bey was trained under French painters Gérôme and Gustav Boulanger was thus influenced by occidental aesthete. But when examined closely his works bear traces of authenticity of a middle Eastern or Ottoman life as in “A man reading Quran”, where we see a set of mosque lamps, intricate lattice works and accurate religious inscriptions. Even the attire of the protagonist is real enough.

What began with Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt in 1801 came to its aggressive highest by the early next century. By 1920s, Europeans had colonised 85 percent of the world with British Empire holding the majority of lands. It wasn’t a rarity to publish a book or exhibit a painting on the exotic “Other”. Thousands of books on Near East, some illustrated came out, they can be said as successors to “Description de l’ Egypte” – a 24 volume documentation of the country, post French colonization not to forget the orientalist who had travelled with Napoléon.

The art movement was an addition to the dominant discourse irrevocable in its cultural essentialism or simply generalization that would serve the colonizer’s interest. In sum it would strip off the fine local and subcultural elements from the visual narrative imposing a European world order metamorphosing into an imperial tool and not just “merely imaginary”.

Said was right and he will continue to be!