In the opening scene of Season 3, Episode 1 of Hulu’s “Only Murders in the Building,” an aging unknown Broadway hopeful played by Meryl Streep auditions for a play directed by Martin Short’s character. Her brief performance is subtle, emotional, luminous. Astounded by its sensitivity, Short walks to the stage and asks the actress, “where have you been?”

What his character means is, “what I’ve just seen from you was brilliant, how come you aren’t a star, how is it possible I’m completely unaware of someone of your clearly enormous talent?

Where have you been?

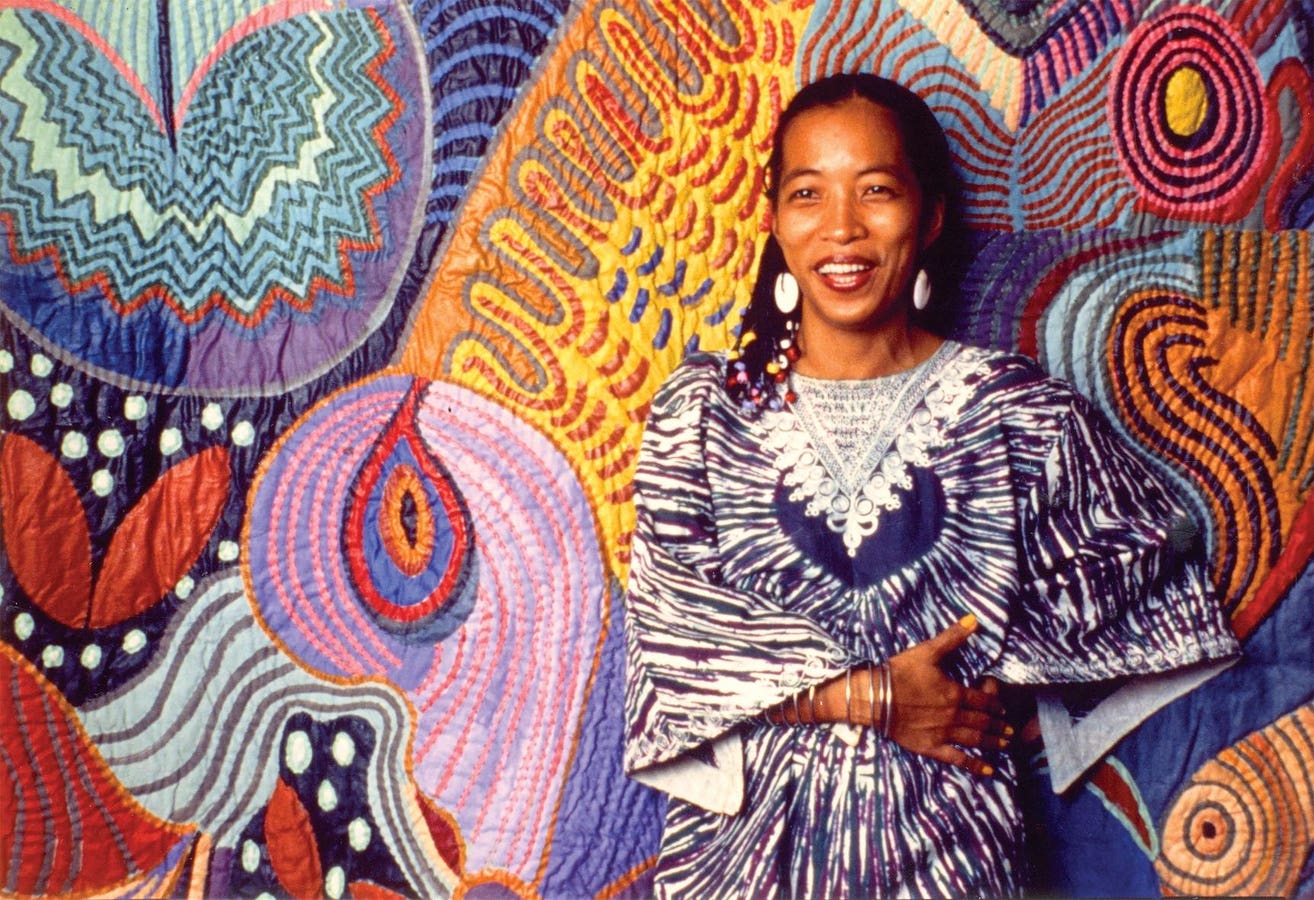

Anyone visiting the breathtaking “Pacita Abad” exhibition at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art will be left wondering, “Pacita Abad, where have you been?”

That seemingly rhetorical question has an answer: everywhere.

Abad (b. 1946, Basco, Philippines; d. 2004, Singapore) and her husband Jack Garrity traveled and lived in over 60 countries. Bangladesh, Papua New Guinea, the Dominican Republic, Kenya, Indonesia, Singapore, Sudan, Yemen.

It was his career as a development economist for international organizations which provided the opportunity for Abad to see the world. She made the most of it, absorbing global traumas and artistic traditions, converting them into a staggering, utterly original body of work, some 5,000 pieces over a 30-year career stretching from the 1970s to early 2000s.

Abad’s travels didn’t feature nights at the Fairmont enjoying spa treatments.

“Instead of being an upper-class wife, she was at the refugee camp,” Eungie Joo, curator and head of contemporary art at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, told Forbes.com.

SFMOMA is the second stop for “Pacita Abad,” the artist’s first retrospective featuring more than 40 major works, rarely seen in public–many monumental in scale–the most significant U.S. presentation of the artist’s multifaceted and mesmerizing art practice ever.

San Francisco at the Crossroads

Born in the Philippines to a family of politicians, Abad was greatly influenced by her family’s public service. In 1970, after leading a student demonstration against the Marcos regime, Abad left her home to escape political persecution.

She intended to move to Madrid to finish a degree in law, but a stop in San Francisco to visit relatives became a long-term stay that would change the trajectory of her life. The Bay Area at this time, 1970, was an epicenter of counterculture and social movements: Black Power and Black Panthers in Oakland, the American Indian Movement and the occupation of Alcatraz, the Chicano Movement, feminism, the anti-war movement.

She met Asian and Latin American immigrants who had left their home countries for economic or sociopolitical reasons. Their stories initially inspired her to pursue studies in immigration law so that she could advocate for their causes.

At the same time, Abad immersed herself in the local art scene and fell in love with art. Though she received a scholarship to attend law school at UC Berkeley following her master’s degree in history at Lone Mountain College (now the University of San Francisco), the artist chose another path. Travel and research. Art soon became the conduit and catalyst through which she advocated for marginalized people.

“She became very immersed in whatever place she traveled to,” Nancy Lim, associate curator of painting and sculpture at SFMOMA, told Forbes.com. “Whether it was Dhaka or to Central Africa, wherever in the world, she always became a coordinate, and was always talking with other artists, immersed with them.”

Who needs a classroom when you have the world?

“She always considered travel and textiles. She encountered textiles by traveling and it was the textiles that were really her teacher,” Lim adds of the artist who only had sparing formal art education. “It was textiles that taught her about abstraction, pattern, ornamentation, color.”

And textile makers, local artists around the globe she deeply engaged with at every opportunity.

“It was a lot of communal making,” Lim explains. “There was so much learning from them, and it was not a distance kind of learning where you open up a book, you see pictures, and then you decide to incorporate that into your making. Wherever she was, she was there, and it was a very tactile and social kind of learning for her. That’s what ended up getting incorporated into all the works.”

Korean ink brush painting. Indonesian batik and Nigerian tie-dye. Sewing and stitching techniques picked up from Rabari women in Rajasthan. Embroidery in Burma and mirror embroidering in India.

Trapunto paintings

These lessons found their greatest expression in her trapunto paintings: canvases that she painted, stuffed and richly embellished with buttons, cowrie shells, beads and mirrors. She created hundreds of these magnificently textured works, occasionally enlisting the help of family members and assistants, thereby evoking the communal making that inspired her.

Abad’s Trapunto paintings hang from the ceiling and cover walls, some stretching 20-feet. They are produced with a riot of vivid, rich colors–pinks and purples and oranges. A shocking use of color.

When asked in 1991 what she had contributed to American art, Abad answered, “Color! I have given it color!”

In addition to the color, the surfaces are magnificently detailed, intricate, ornate.

Featured in the exhibition are works inspired by Indigenous mask traditions Abad encountered in Asia, Africa, Oceania and the Americas, including Masks from Six Continents (1990–93), originally installed in 1990 as a 50-foot-long fabric mural commissioned for the Washington, D.C. Metro Center.

For the European continent, which has no mask making tradition, she used a mask from Congo.

“The reason why she used that particular motif is that it was meant to evoke Europe’s wholesale appropriation, modernism’s appropriation, of African art forms,” Lim explained. “That’s where a lot of that interest came out of, to think about who is appropriated, what cultural traditions, what artistic traditions, and then to make space for those cultural traditions themselves apart from colonial gaze.”

Abad was well ahead of her time in making this connection and calling it out.

“Now we’re really acknowledging–in the last 20 years–that modernism took the abstraction of Indigenous cultures, took the abstraction of Africa and claimed it as their own, but she was introducing that idea quite early through a way of making work that lay between abstraction and representation,” Joo said. “That’s probably where (Abad’s artmaking is) unique. She was making a gesture that used a ritual object, that recalled a traditional object, that played between the representational and the abstract, and then, of course, the use of color, which is completely fabricated by her. It’s beyond. It creates a different feeling than anything traditional because of that other layer.”

Demonstrating Abad’s astonishing artistic vision, “Pacita Abad” further includes a separate series of trapunto paintings inspired by her learning Scuba diving in midlife. Her “Underwater Wilderness” pieces reflect the electric colors of marine wildlife creating a subaquatic world teeming with tropical sea life through a combination of oil and acrylic paints, plastic buttons, rhinestones and iridescent fringe on stitched and padded canvas.

They’re astonishing, like walking into an aquarium thanks to SFMOMA’s moody install.

Women and Children

While most of the attention in “Pacita Abad” will understandably go to her eyepopping trapunto paintings, the handful of paintings on canvas presented in the show demonstrate her as a master there as well.

Abad’s Social Realist works from the late 1970s and early 1980s include powerful portraits of individuals escaping political persecution and economic injustice. Look at the faces. She didn’t see these people, she felt them–women, children, refugees.

Her first significant body of work, these drawings and paintings emerged from on-the-ground visits to refugee camps along the Cambodia–Thailand border, an area ravaged by decades of conflict.

Flight to Freedom (1980) from Abad’s “Cambodian Refugee” series is as good as history painting gets. It’s Goya’s Third of May, 1808 good. Manet’s The Execution of Emperor Maximillion good.

The 15-foot-wide artwork depicts families–mostly women and children–carrying their sparse belongings, the human and material remains of Cold War-era proxy wars in Southeast Asia.

Where are they going? Anywhere. Nowhere. Somewhere else.

Mostly women and children.

Abad’s paintings from 40 years ago could stand in for Gaza, Sudan, Armenia, the southern U.S. border, anywhere refugees–mostly women and children–find themselves in the crosshairs of colonization, genocide, war, displacement, misery, suffering. Artistic genius like this speaks to its time, past times, future times.

History painting needs women artists to take the spotlight exclusively off the combatants and provide equal, if not more attention, to the so-called “collateral damage”–women and children.

Abad was a witness. And she brought it to her work long before doing so was fashionable, as it is now.

“If you’re from those places, living this reality of martial law, living the reality of identifying with people who are being displaced because of a variety of reasons, whether natural or manmade, or a combination therein, when you identify with people who are experiencing this displacement, you might address it earlier or in its time,” Joo said.

How could anyone look at these people, Abad’s portrayals, and turn their back? Yet millions do, governments do, the American government does, even today.

She put a face –a woman’s face, a child’s face –on crises that are often summarized by figures. Ten thousand refugees. One hundred thousand refugees. Numbers are always easier to ignore than faces.

She painted with deep humanity. Tenderness, providing just enough detail to get the point across.

“This is mankind,” Joo said. “We were given thumbs and look at what we’ve done with this, but it’s true. We have this ongoing history of colonization and displacement that is maybe the crisis of our time, of our 200 years or 500 years if we look at epics in that way.”

Abad insightfully described her paintings thusly, “after the media coverage ends, my paintings keep staring at you.”

Where have you been Pacita Abad?

She’s been there, here, all along. It’s the world that has finally caught up.

“Pacita Abad” originated at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, the organizing institution, in 2023. It will remain on view at SFMOMA through January 28, 2024, before heading to MoMA PS1 in New York April 4 through September 2, 2024, and then the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto October 12, 2024, through January 19, 2025.