Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The Mexican revolution was finally over. The civil wars and agrarian uprisings that overthrew a dictator and established a constitutional republic ushered in a new era of Mexican nationalism. In Frida Kahlo’s “Self-Portrait with Monkey” (1945), the artist, dressed in a robe from the indigenous Tehuana people of Mexico, trusty spider monkey at her shoulder, throws us a haughty glance from under her unibrow. Celebrating pre-colonial cultures and female empowerment, this self-portrait captures a mood of defiance and confidence.

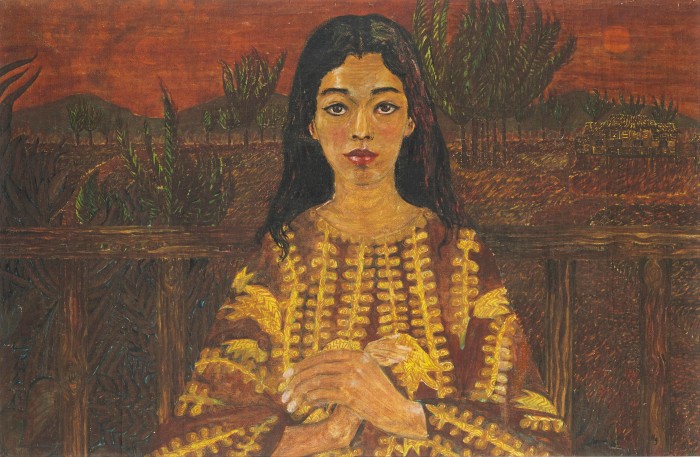

Contrast this with “Self-Portrait” (1958) by Patrick Ng, rendered a year after the Federation of Malaya, formerly British Malaya, became independent. The artist, a Chinese man, has depicted himself as a Malay woman. The queering (from man to woman, Chinese to Malay) makes this a slippery painting. On one level, it seems to be expressing ambivalence about “Malayanisation”, a national development programme to build a homogenous identity in a multiracial state. But it could also be read as a vision of a future society of radical fluidity, where typical markers of identity can be transcended.

Two self-portraits made during periods of national transformation; two very different moods. They are placed side by side in Tropical: Stories from Southeast Asia and Latin America at National Gallery Singapore, billed as the first major comparative survey of art from the two regions. One of its propositions is that self-portraiture was a strategy that artists from both sides of the globe used to comment on societal change and to imagine new worlds.

But is this a strategy exclusive to these regions? Self-portraits have everywhere and always offered commentary and vision. Beyond this, the show connects the art from diverse territories under a grand narrative of anti-imperialist resistance and sundry other rebellions. Besides self-portraiture, other threads in the show include the incorporation of local traditions, such as in the stacked totems of Rubem Valentim that reference Afro-Brazilian customs, as well as the innovative use of crafts, as seen in Barbara Sansoni’s geometric handwoven textile works suspended from the ceiling.

To unite all this, the curators propose a concept called “Tropical”, described as a “defiant attitude” that “allowed for the most imaginative possibilities to emerge even from the most trying of circumstances”. While not very illuminating (even verging on reductive, as it suggests that equatorial types are governed by their passions), it does generate an atmosphere of solidarity: the tropical as a hothouse space of restless ferment and unruly fecundity.

Is this convincing? Only if you take “tropicality” as a poetic mood or a speculative proposition, which allows for some fudging of timescales and the fusing of diverse liberatory struggles. The sweeping concept takes some serious creative licence and does not properly account for global conditions. The curators propose that although independence in both regions happened at different periods — most of Latin America between 1808 and 1826, south-east Asia between 1945 and 1957 — their art histories followed similar trajectories and can be mapped on to each other. But as this is mostly a 20th-century painting show, the Latin American artists are mischaracterised by this line of reasoning; by that time, some of them were fighting local dictators rather than colonial overlords.

But this is an ambitious and meaningful project. As interest in the art from the Global South grows, there is particular focus on south-to-south exchanges. Here, two regions occupying peripheral roles within a “global” history of Eurocentric modernism have placed themselves centrestage. White people are not invited, with the exception of Paul Gauguin, who opens the exhibition as a common enemy. His “Poor Fisherman” (1896), showing a naked native from French Polynesia drinking from a coconut shell, exemplifies lingering stereotypes of the tropics as idle, primitive and backward.

Over the course of the show, this trope gets soundly rebutted by more than 200 artworks showing labour, resistance and futuristic visions of Global South solidarity (even before the term was coined). The argument is borne out in three sections, roughly chronological in order. The Myth of the Lazy Native explores how artists resisted European representations of colonial subjects in a series of figurative paintings that celebrate local life, industry and cultures. Here, we have a Brazilian fruit-seller on a boat with a wonderful expression of bored disdain (Tarsila do Amaral, “The Fruit Seller”, 1925), a Mexican woman making tortillas (Diego Rivera, “Woman Grinding Maize”, 1924) and a street-theatre performance in Jakarta (Hendra Gunawan, “Monkey Dance”).

The second section, This Earth of Mankind, roughly maps on to the post-independence period, in which artists grappled with national identities and melded traditions with experimentation. As part of the exhibition’s populist manoeuvres, a mirror has been put between two Indonesian modern masters for visitors to take selfies. On the left, we have Chinese-born Lee Man Fong’s careful self-portrait dressed in a tropics-appropriate white T-shirt and surrounded by Greek statues, signalling his parity with European traditions; on the right, the Indonesian artist Affandi’s visage composed of chaotic squiggles, achieved by squeezing tubes of paint directly on to the canvas and smudging them around with his fingers. Following them is a pageant of self-portraits that eventually culminates in an exploration of how artists elevated craft traditions to art.

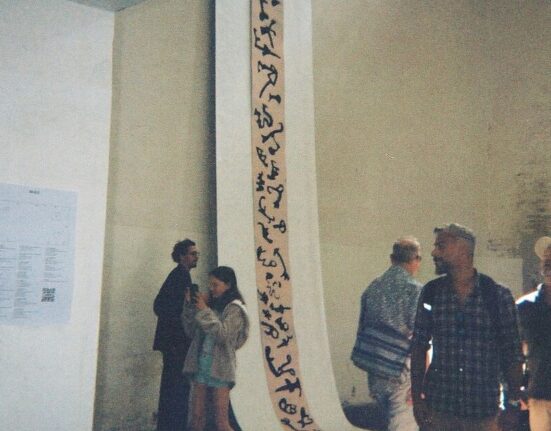

Finally, The Subversive brings us to the present day. This is where the exhibition becomes the most multidisciplinary, with installations, videos and sculpture. Curatorially, it’s a bit of a free-for-all: so long as the artist is challenging something, she’s in. But it ends up being the strongest section. Liberated from a linear narrative, the works speak a language of defiance, fierceness, sensuality and mystery. Bali’s I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih’s sinuous figures with explicit genitalia upend sexual conservatism with joyous lasciviousness.

It is also here that the western category of “art” gets destabilised by Singaporean Malay artist Mohammad Din Mohammad’s talismanic paintings. As a Sufi mystic and healer, his works are packed with pieces of wood, animal bone and shells in crowded compositions which are believed to be therapeutic to the viewer. One wonders whether “tropical” could involve a fusion of different paradigms, such as art, spirituality and medicine, which make up singular practices in the Global South that cannot be easily assimilated into western aesthetic categories? In any case, this exhibition is a starting point for imagining how we can broaden the ways we narrate creative processes from around the world.

To March 24, nationalgallery.sg