The 59th Venice Biennale opened against the backdrop of Russia’s brutal invasion of Ukraine and the continuing rise of authoritarianism in Eastern Europe, as Vladimir Putin’s close ally, Viktor Orban, had just won his fourth term as Hungary’s prime minister. At this moment, defined by war crimes and the oppression of minority groups, it seems inevitable to question the significance of the prestigious art event, all too often centered around privilege and exclusivity. However, Ukrainian artists and curators remained committed to acting as cultural ambassadors in Venice and making their voices heard against Russia, whose national pavilion remains empty after its organizers withdrew in protest of the war. Below are highlights and historic firsts by Eastern European artists and curators across this year’s Biennale.

Fountain of Exhaustion. Aqua Alta by Pavlo Makov at the Ukrainian Pavilion

The Ukrainian Pavilion became the center of attention in the Arsenale, where delegations of diplomats gathered to take photos in solidarity and art crowds mingled, sometimes discussing news related to the war. Unaffected by this movement of visitors, water relentlessly flows and drips through 78 funnels making up Pavlo Makov’s iconic sculpture “Fountain of Exhaustion,” initially conceived in the mid-1990s as a poetic reflection on the ruined infrastructure of Kharkiv, the post-Soviet city where Makov is based. The work is ultimately about “the exhaustion of the society […] and the willpower to continue,” as Makov said in a press conference, but after Russia invaded Ukraine on February 24 and the military shelled cities like Kharkiv, the piece emerged as a symbol of Ukrainian resilience — paid in tears and blood. Curators Borys Filonenko, Lizaveta German, and Maria Lanko deserve all the praise for getting the pieces of the sculpture out of the country and delivering them safely to Venice by car.

After Dreams: I Dare to Defy the Damage by Zsófia Keresztes at the Hungarian Pavilion

An unlikely counterpart to Makov’s fountain, Zsófia Keresztes’s surreal and highly Instagrammable sculptures in the Hungarian Pavilion offer a feminist take on empathy, solidarity, and alienation in the face of doomscrolling and social media activism. In her glossy mosaic works, amorphous body parts go rogue, metamorphosing from one shape to the next, rattling the chains that hold them together. A shopping cart, identical to one that the artist stumbled upon during her first site visit in Venice, has been transformed into a tank, armed with pointed breasts and teardrops, ready to go to war, while the main “altar” looks out with a pair of icy eyes clamped open with chains. These sculptures, constantly battling with themselves, confront us with questions: What are the limits of attention, empathy, and care in the digital realm, and where do our tear emojis and solidarity posts take us in times of real crisis?

The work was inspired in part by “hydrofeminism, and this idea that the water (tears, sweat, etc.) circulating in humans and other species somehow interconnects us with the natural environment,” Keresztes told me. Notably, this is the first time that both the Hungarian pavilion’s artist and its curator, Mónika Zsikla, are women. Considering that the country’s cultural institutions have become more conservative in showcasing feminist and queer art due to the growing control of the current right-wing government, it is celebratory that such a poignant body of work could be installed at the pavilion.

Re-enchanting the World by Malgorzata Mirga-Tas at the Polish Pavilion

Malgorzata Mirga-Tas has made history as the first Roma artist in the Biennale’s over 120-year history to represent a country in a national pavilion. (While the Roma are the biggest ethnic minority in Europe, its artists have historically been underrepresented at the Biennale and elsewhere; Paradise Lost, The First Roma Pavilion, curated by Tímea Junghaus in 2007, was the first exhibition to feature a selection of international Roma artists in Venice.) In Mirga-Tas’s monumental textile installation, spanning the interior and exterior of the Polish Pavilion, spectacular textile pieces hang from the facade, depicting a reinterpretation of the Wheel of Fortune from a famous 15th-century tarot deck and alluding to Roma’s history of fortune-telling.

In the interior, Mirga-Tas mapped the architecture of the Renaissance-era Palazzo Schifanoia of Ferrara onto the walls. “The zodiac belt running across our textile palace depicts ‘my own stars,’ wonderful Romani women,” Mirga-Tas shared in an email. “They are my heroines, famous activists, poets or artists, but also ordinary wonderful women, who with their lives and character influenced not only my life but also the lives of other[s].” The pavilion was curated by Wojciech Szymański & Joanna Warsza.

Nikita Kadan at Piazza Ucraina and the Scuola Grande della Misericordia

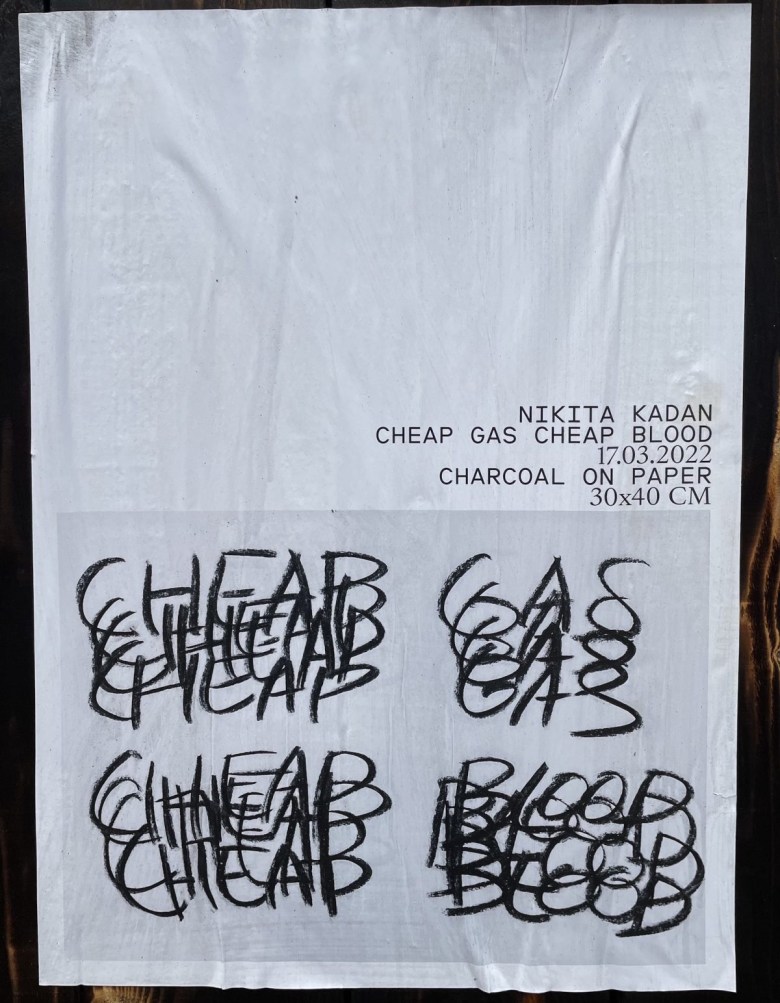

Since the beginning of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Kyiv-based artist and activist Nikita Kadan has emerged as a source of information on the escalating situation in the capital, posting images of Ukrainians’ efforts to preserve their monuments, photos of shelled buildings, and his own drawings. A few of them, including a charcoal work titled “CHEAP GAS CHEAP BLOOD” (2022), have been reproduced on posters, exhibited on scorched wooden posts in the Giardini’s last-minute addition, Piazza Ucraina (“Ukraine Square”) — an open-air meeting point for Ukrainian resistance, organized by the curators of Pavlo Makov’s pavilion and showcasing works by Ukrainian artists made since February 24.

Kadan’s work can also be seen elsewhere in Venice at the PinchukArtCentre’s solidarity show This is Ukraine: Defending Freedom at the Scuola Grande della Misericordia, where he is exhibiting “Difficulties of Profanation” (2015-2022), a sculpture first presented at the Ukrainian pavilion in Venice in 2015. The new, larger iteration combines the initial materials Kadan collected from the conflicted Donbas region in 2015 with a selection of archival images and objects gathered from the streets of Kyiv in March 2022.

Kadan had mixed feelings about accepting the invitation to attend the opening of This is Ukraine in Venice, leaving his country for the first time since the war broke out.

“It seems problematic to me that I was one of the few artists or cultural actors who were given this permission to go abroad, and I don’t think that being an artist is a reason to have more safety than others,” he told me.

Reflecting on the two solidarity exhibitions, Kadan continued: “Before February 24th, most participants would have felt really problematic about such a strong presence of the state in our exhibitions, about the signature of the President on the banner of our show in Venice. But today, we are in the regime of urgency and survival, so we take the methods which will be effective here and now, but remain able for critical reflection.”

“Encyclopedia of Relations” (2022) by Alexandra Pirici in The Milk of Dreams

Perhaps the pandemic is still to be blamed for the lack of performance-based works in this year’s Biennale. Notably, the only live performance in the show is Biennale veteran Romanian artist Alexandra Pirici’s “Encyclopedia of Relations,” hidden away inside the labyrinth of the Giardini’s Central Pavilion exhibition, curated by Cecilia Alemani. During the show’s open hours, Pirici’s performers, six at a time, flow through the space alone or together, seamlessly interacting with each other and the audience through movement, dance, singing, or spoken word. In one memorable episode, they performed an adaptation of Toni Braxton’s 2000 song “He Wasn’t Man Enough,” twisting the lyrics to sing about planetary collapse and the abolition of private property, accompanied by what seemed like a TikTok dance. Pirici’s performance is a reminder of the joy of connecting with strangers through movement and bodily interaction at a Biennale — and in pandemic life in general — oversaturated by images, objects, and screens.

(Note: I initially set out to write about Adina Pintilie’s presentation for the Romanian Pavilion, You Are Another Me — A Cathedral of the Body. A typo in the Mayan greeting “In Lak’ech Ala K’in” (“I am you, and you are me”) referenced in the Italian version of the curatorial text at the entrance seemed disrespectful of Mayan culture and could not be ignored in the evaluation of the pavilion. I thank artist Judit Kis and Mayan artisan and educator Chakceel Rohen for pointing out this mistake.)

Mihaela Dragan, “Healing the Transgenerational Trauma” (2022) in Roma Women: Performative Strategies of Resistance

Commissioned by ERIAC (European Roma Institute for Arts and Culture) and curated by Ilina Schileru, the exhibition Roma Women at the Palazzo Loredan showcases video works. In Mihaela Dragan’s video performance, the Bucharest and Berlin-based actress and artist uses witchcraft to heal and liberate her community from intergenerational traumas inherited from slavery, discrimination, and the Holocaust. In the footage, the artist is seen against the backdrop of an interior evoking a Roma home (an installation by painter Eugen Raportoru, whose exhibition, Eugen Raportoru: The Abduction from the Seraglio is showcased alongside Roma Women in Palazzo Loredan), which she activates by making a potion and casting a spell. While more modest in scale and execution than Tourmaline’s “Mary of Ill Fame” (2020-2021), a video installation fabulating a narrative around the life of Black trans woman Mary Jones showcased prominently in the Giardino delle Vergini, an array of connections can be made between the two works, centered around self-liberatory practices and healing from violent pasts.