Just as Britain’s town centres are increasingly alike, with the presence or absence of key chains a ready reckoner of relative affluence, the Galataport is fluent in the international argot of urban regeneration. In the tradition of London’s Bankside/Tate Modern, industrial Bilbao/Guggenheim Bilbao, the Galataport/Istanbul Modern waterside development signals a free, open, modern city, ready to do business with the western world.

It’s a language well understood by President Erdoğan, who seized the opportunity to open Istanbul Modern on May 19, a public holiday just after the first round of presidential elections. Undoubtedly, the occasion has eased his recent transformation from major league villain to friend of the west, burnishing his credentials as a prospective member of the EU and Nato.

His speech, says Asena Günal, director of Anadolu Kültür, an Istanbul-based cultural organisation that champions free expression in Turkey, sounded a gentler note than much of his rhetoric around art. Though he complained that pro-government artists were sidelined, he emphasised government investment in culture.

“Normally he targets artists”, she says, comparing the speech to one made 18 months earlier, at the opening of the rebuilt Ataturk Cultural Centre in Taksim Square. “At that opening he was really furious, targeting the people who were at Gezi Park,” she says.

Günal has personal experience of falling foul of the Turkish government. Her colleague, the chairman and founder of Anadolu Kultur, Osman Kavala, is six years into a life sentence. He was accused of orchestrating and financing the Gezi Park protests in 2013, and the failed coup attempt in 2016, and found guilty on the Gezi Park charges. The European Court of Human Rights has said there was insufficient evidence he committed an offence, and that his arrest was an attempt to “silence him and dissuade other human-rights defenders”. Günal has herself been illegally detained, and harassed, and several other colleagues have been sentenced to 18 years in prison, with no evidence.

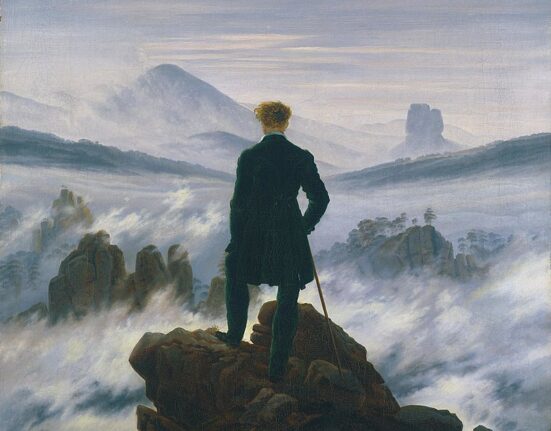

The Gezi Park uprising of 2013 is universally understood as a turning point in Turkey’s recent history. It was triggered by government moves to demolish Gezi Park, a much-loved area of green space just off Taksim Square in central Istanbul, and with it the Ataturk Cultural Centre, which had been due to be renovated, in order to make way for a shopping mall, styled as a neo-Ottoman barracks. A peaceful sit-in was violently dispersed, triggering nationwide protests against the government, and specifically its curbs on free speech, the suppression of women’s rights including access to abortions, and press freedom.

Since then, the government has imposed increasingly draconian restrictions on people’s daily lives, and Günal says that after Gezi “the state took harsher measures, increased the police violence, increased the security measures, and especially after the coup attempt in 2016.”

When the AKP (Justice and Development Party) emerged in 2001, it put forward a modernising agenda, combining social conservatism with economic liberalism, that included petitioning for membership of the European Union. Joining the carousel of the global art market was a natural step for Turkey at this point – art attracts money, and carries an aura of moral integrity, implying certain standards, and a liberal, tolerant society.

In a cruel twist, Istanbul Modern and Turkish art is all too easily recruited as an aid to Erdoğan’s ambitions on the world stage. The building itself, with its Italian “starchitect” pedigree, effortlessly puts it at the service of a homogeneously Eurocentric narrative. And while its inaugural exhibition Floating Islands is its most comprehensive collection exhibition to date, presenting works by more than 110 artists since 1945, its modishly international agenda obscures and dilutes much that speaks specifically of Turkish experience.

To some extent, this is a consequence of the art, which has to a significant extent been shaped in response to western influences. As with other Middle Eastern countries, historically, artists were encouraged to study in Europe, and a good proportion of Floating Islands is dedicated to the “New School of Paris”, which includes work by Turkish artists there from 1945-1960, among them the abstract painter Fahrelnissa Zeid (1901-1991), the subject of a 2017 Tate Modern retrospective, Selim Turan (1915-1994) and Albert Bitran (1929-2018).

Still, even artists whose work shows the influence of the School of Paris is often tempered with a non-western aesthetic. In Sleeping Beauty, 1973, Nurullah Berk, who studied in Paris with the cubist painter André Lhote in the 1920s, reclaims the exoticising motif of the odalisque favoured by painters from Ingres to Matisse. The multiple planes and disrupted perspective used by Matisse and Picasso are treated here as decorative geometric surfaces, derived from Islamic art.

Exploring the collection through a Turkish, rather than a western prism, presents a fundamental problem, as explained by the American writer Suzy Hansen, in the New York Times in 2012. She noted the challenges of compiling a coherent history of 20th-century Turkey, the tumultuous recalibration that occurred when the Ottoman Empire collapsed, and Ataturk founded the Republic in 1923, followed by many more upheavals that have left today’s generations of Turks with a fractured sense of identity and history. Vasif Kortun, still a major player on the Istanbul art scene, told her: “The 20th century is the lost century for this city.” The construction of a Turkish history of art remains a work in progress.

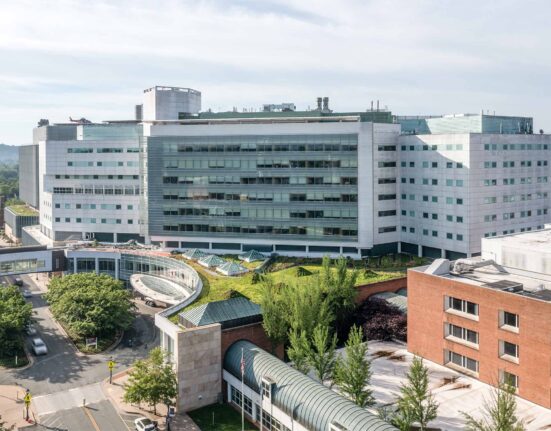

Just as problematic, the museum’s international, western-focused agenda is at the heart of its identity; since its inception in 2004 as Turkey’s first museum of modern and contemporary art, the transformation of the museum from a disused warehouse in the run-down industrial docks to shiny new cultural destination has run parallel to Istanbul’s emergence as a player on the contemporary art scene. And, as the writer Kaya Genç points out, “The rise of Istanbul as a potential hub for contemporary art in the Middle East was tied to the rise of the AKP from the get-go.”

The AKP’s neoliberal ambitions provided a fertile environment for the emergence of a privately funded, commercially lucrative art scene in the 2000s and in her book Turkish Awakening, Alev Scott explains that for the super-rich “building a name as a major player on the arts scene in Istanbul is the ultimate display of peacockesque ostentation.” She notes that Istanbul’s three galleries in 2000 had “multiplied a hundredfold” by 2014.

In this context, the lack of state support for the visual arts looks like the logical consequence of a free-market economy, in which a small group of Istanbul’s wealthy business dynasties provide financial support not just for the visual arts, but for music and cinema.

In reality, the lack of government support reflects its deep distrust of the arts, which in 2011 the minister of the interior Idris Naim Şahin described as the “backyard” of Kurdish terrorism. According to Kaya Genç, increase in anxiety around artists can be tied to the economic transformation of Turkey in the 1980s, as the cold war thawed and the economy was liberalised. Previously benign, state-supported artists operating via various official institutions became increasingly independent of the state: “With the rise of contemporary art and post-modern, post-colonial literary figures, the once docile, state-friendly artists and authors became the gravediggers of Turkey’s state apparatus,” he writes.

Gezi Park confirmed the connection between artists and protest, while also setting a precedent for public space as a contested sphere: the regeneration of areas of the city often entails as much destruction as creation, and at least two historic buildings were destroyed during the Galataport redevelopment, not to mention the human cost of the rapid gentrification of an entire district.

Today, the lack of state support does confer a degree of autonomy on visual artists, compared to filmmakers, for example, who receive state patronage and are therefore more likely to have pressure put on them. The makers of the 2022 film Burning Days were asked to return the funding they had received from the Ministry of Culture because of its references to homosexuality.

Clearly, however, private and commercial funding sources are not autonomous, and need to remain on the right side of the government. This implies a degree of self-censorship, something that Günal notes is trickier than it might seem. “It’s a big discussion, actually, I mean, the relation of the regime with the art scene, what they understand of the arts, which kind of arts they want, which kind of art they don’t, and especially contemporary art.”

These subtleties emerge most forcefully in differences of context: the last Istanbul Biennial, which took place in autumn 2022, was dissenting in a way that is unthinkable at Istanbul Modern.

Both institutions are funded by the Eczacıbaşı family, whose IKSV (Istanbul Foundation for Culture and Arts) has been a beacon of art, film and music since 1973. The core collection at Istanbul Modern was established by Dr. F Nejat Eczacıbaşı as a personal collection of “milestones of Turkish art”, and the family continues to donate works, and is represented on the board.

Certainly, its holdings are diverse, no surprise perhaps for a museum that claims: “We care about exhibiting the works of international artists who play an active role in the global transformation of contemporary art.” Such an anodyne claim is perhaps rather smarter than it sounds, however: the museum’s Women Artists Fund is unremarkable in an international context, but perhaps less so in a Turkish one. Its inclusion of work about transsexual and transvestite people, women, and other marginalised groups is here protected by the global aspirations of the president himself.

Still, the flipside of Erdoğan’s global tendency is the targeting of the LGBTQ community, and art galleries brave enough to show such material. Last month, a new art space called ArtIstanbul Feshane was temporarily closed after conservative protesters objected to work they deemed indecent. Günal tells me that when an exhibition by queer art collective Bound/less opened at her own organisation’s gallery DEPO last month, “I had to invite two security people and two lawyers in case people might attack, or in case police might attack.”

Homosexuality has never been illegal in Turkey, and the oppression of LGBTQ people is a recent development, imported from other Islamic countries, and other authoritarian regimes, and ramped up during the election campaign. To Asena Günal, it is entirely confected by the government: “They’re creating scapegoats and finding groups to target and to fight with.”

Istanbul’s smaller venues are at risk of government interference and worse, and against this backdrop, the opening of the new Istanbul Modern is a major achievement. But if it is to avoid being used as a sop to the international community, a fraudulent proof that all is well, the curators need to work hard to make the art in their collections speak as loudly as it can.