In February 1780, an Englishman arrived in Madras, weary and sick from his year-long journey to India. As a small boat took him ashore, he was struck by the clear blue sky, the bright sandy beach and the flat-roofed white buildings in the distance – a sharp contrast to his hometown, London.

These were the times of the Anglo-French wars, with the East India Company engaged in battle with Hyder Ali of Mysore. The Englishman was confined to the area near Fort St George, which had been the English East Company’s stronghold in Madras since the 17th century. He spent his time sketching the countryside around. After all, that is precisely why he had travelled to India: William Hodges was the East India Company’s first official landscape artist.

Hodges was perhaps the most illustrious of the many artists who began to arrive in India from the late 18th century. European artists had been travelling to India earlier too. But with the East India Company establishing its power and the growing competition in the art market in London, more artists set off for the distant colonies in pursuit of fortune and fame. In the era of industrialisation and colonialism, art was growing into a lucrative business. But then, like now, the lives of artists such as Hodges remained precarious, dependent on patrons to hand out commissions.

Colonial trade and art

Expanding trade networks at the end of the 15th century had enabled a greater movement of goods and people. Alongside colonialism and its culture of consumption of fine textiles, spices, tea and opium among other commodities, a global market emerged for art and aesthetic objects. Artistic objects and artists began to flow across the world.

The East India Company was a key beneficiary of the global art market, just as it was of the trade in other commodities. By the 18th century, London had emerged as a hub for artists due to the passage of the Hogarth Act of 1735, which extended the copyright concepts of printing to the visual arts. Artists in London gained secure artistic copyrights, unlike in European art hubs where copies and duplicates of artworks were freely sold by art dealers.

But it was the revolution in printing technology in the 18th century that galvanised the art business, allowing for the production of multiple, faithful copies of artworks that were legally authentic for sale.

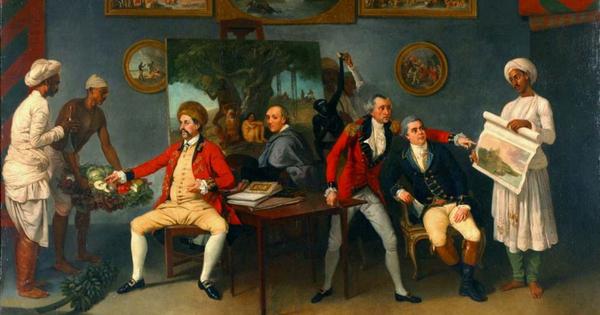

The emerging middle class in Europe, America and India became patrons of art. One of the biggest sponsors of art was the East India Company. It spurred the creation of an empire of imagination suitable to the aesthetic sense of the Company ideology.

Many artists travelled to colonised lands, often with the army, to capture scenes of battles, landscapes or paint the picturesque and the sublime for audiences back home. This came with a price: artists had to seek permission from the Company to travel to colonial territories and pay it handling charges. Hodges, too, became an itinerant artist.

Ethnography became an integral aspect of the visual renditions of India as artists drew landscapes, sceneries, monuments, rulers, customs, costumes and the ordinary people of the diverse subcontinent. Soon, exhibitions of these works drew significant audiences willing to pay to view artwork depicting the colonised lands, their people, landscapes, cities, and cultures.

William Hodges in India

Even before Hodges came to India, he had an unparalleled career as an artist. He started out painting backdrops for theatres and rose to become a member of the prestigious Royal Art Gallery. He accompanied British explorer Captain James Cook on his voyage to the South Pacific Ocean, during which he painted scenes of the islands, the bays and its residents.

Since he was an established landscape artist in London, Hodges was invited to Calcutta by Warren Hastings, the first governor general of Bengal. After obtaining permission from the Company in London, he set off for India in 1779. He arrived in Madras the following year.

Once Hodges had recovered from illness, he made several drawings in the Madras presidency, especially of temples in Tanjore, as Thanjavur was known then.

In his book Travels in India, Hodges writes that he drew the famous Chola-era Brihadisvara Temple in Thanjavur – or “pagoda” as he called it. This, along with other drawings, were sent to London aboard the General Barker East Indiaman. But the ship was wrecked off the coast of Holland in 1781 and Hodges’s drawings were lost. He later made an aquatint of the Thanjavur temple based on the original drawings of a surveyor.

In February 1781, a year after his arrival in India, Hodges finally reached Calcutta where Governor Hastings arranged a salary of Rs 12,000 per annum to be paid by the English East India Company. Hastings commissioned Hodges to create a kind of visual chronicle of the rising British empire in India.

A month after his arrival in Calcutta, Hodges travelled to Rajmahal Hills in Bihar and then to Bhagalpur. The Commissioner of Bhagalpur, Augustus Cleveland, became another of Hodges’s patrons. Hodge later travelled through North India, making on-the-spot drawings of landscapes, monuments, people and customs.

Hodges made around 90 on-the-spot drawings as well as some oil on canvas during his stay in India. Among the most notable are the ghats of Benares, the Gwalior fort and the Taj Mahal.

Hodges left India in November of 1783 for London. Before leaving, he gifted five paintings to the Company as a token of gratitude. These were views of Agra, the tomb of Mughal emperor Akbar, the Gwalior fort and the palace of Lucknow.

Upon arriving in London in June 1784, Hodges began work on his Select Views in India, a set of 48 aquatints based on his drawings, which he dedicated to the Company. Years later, in 1793, Hodges published his Travels in India in the Years 1780, 1781, 1782 and 1783. He exhibited his works at the Royal Academy on many occasions and was appointed as Resident Artist at the Royal Academy.

But in the end, it would not be enough and Hodges’s story had an unhappy ending.

Colonialism’s visual affair

British rule in India is largely understood in terms of its political economy. with the discussion focusing on commodity and industrial capitalism and the impact of colonialism on the British and Indian economies.

But colonialism was immensely sensorially figured, as much as it was economically so. From the commodities of consumption, the taste of spices, smell of perfumes and the feel of fabrics, colonialism also enabled the aesthetic pleasure of viewing the exotic India and Indian art.

Historian Holger Hoocke has pointed out that colonialism was an intensely visual affair. Artworks from the colonial period of India are intertwined with the commercial and imperial ideology of the East India Company, which linked India to the global art market.

From the late 18th century until the rise of photography as the dominant means of artistic consumption in the 19th century, this visual culture involved Indian artists working for the British, British artists working for Indian and British patrons, and British artists in England. Hodges’s life as an itinerant artist in England, Pacific islands and India reflects the larger phenomenon of the proliferation in artistic production and consumption from the late 18th century.

The search for patronage, of newer and novel themes for their canvases and making a name and fortune for themselves in the times of colonialism were the quests of many aspiring artists across the western countries. But this thrill was not without its travails.

By the time Hodges left India in 1783, the art market in Calcutta had become extremely competitive and patronage was hard to find for the many artists arriving in the country. Travelling in Presidency towns in India required a lot of money. Not all artists had an invitation from the likes of Hastings, neither were they salaried artists.

Competition among artists in India was fierce. Many of them moved from one native court to another in search of greater patronage and remuneration. But the declining status of Indian rulers made patronage scarce.

Success, struggles of artists in India

Artists interested in travelling to India had to seek permission from the East India Company and sign a bond of good conduct.

East India Company ships charged money to handle artworks, including the cost of packaging and freight. The artworks were subject to import duty which varied, depending on the size of the canvas.

Not all artists had it as easy as Hodges. Ozias Humphry, who initially had John Macpherson as a patron in Madras, tried his luck at Lucknow. But given the success of painter Johann Zoffany and Scottish artist Charles Smith there, he found it difficult to establish himself. He then went to Calcutta.

In Calcutta, landscape artist George Chinnery’s providence made it difficult for Robert Home, one of the most established portraitists, to carve a space for himself.

But then there were also some who were successful in the commercial sense.

Tilly Kettle, patronised by Nawab Shuja ud doula of Oudh, was one of the earliest and considerably successful artists of the times who worked in India from 1769 to 1776. His portraits cost Rs 4,000 to Rs 5,000 each.

Landscape artists like Thomas Daniell and William Daniell (in Upper India), James Wales and John Jukes (in Bombay), and George Chinnery (in Calcutta) all made their names through their artworks, but not everyone earned a fortune.

The Daniell brothers had to raise money through a lottery to fund their artistic journey in India. George Chinnerey, despite his artistic fame, had incurred so much debt that he had to flee to Macau in China to avoid debt collectors.

Colonial gaze on canvas

Today, these paintings reflect the local artistic style intertwined with British aesthetics. The colonial gaze of exotic India is conspicuous in imperial art. Far from the chaos of the period and the killings and destruction characteristic of wartime, the landscape artists of colonial India presented a tranquil, idyllic portrayal of the cities and countryside.

In many ways, the artworks were seen as a visual chronicle of the Company state in India, a narrative that did not capture the colonising process.For instance, Hodges much famed Ghats of Banaras made during the conflict with Warren Hastings, when he accompanied him, is in sharp contrast to the arrest of Chait Singh and the resulting battle.

Even when the subject on the canvas was a battle scene, it conformed to imperial ideology, valourising the sacrifices of the Company in the wake of “atrocities” by the natives.

Death and debt

And what of Hodges?

He ran into financial hardship following the high cost of publishing his books on his art in India. His attempt to capture the landscape of war that England was involved in at that time was also not received well. The arthouse Christie’s sold the William Hodges collection. His view of the Taj Mahal was sold at a price of £35 10s – its current price would be around £2,700.

Eventually, he moved with his family to Devon. He tried his luck in banking – another profitable business at the time – but failed miserably. He died soon after in 1797, rumoured to be by suicide. In his letter to his brother- in-law, Hodges willed the paintings off for auction to pay off his debt.

Many of his paintings in the collection of Warren Hastings were sold by Christie’s. From one account, Hastings sold 13 of them right after Hodges’s death as was willed by Hodges that his artworks be sold to liquidate his debts.

Sonal is an Assistant Professor at the Department of History, Shivaji College, University of Delhi.