Coco Chanel was said to have owned anything from 21 to 32 Chinese Coromandel screens in her lifetime. She moved them from home to home, using them as decoration as well as inspiration. With figures and flowers, hunting scenes and Chinese dignitaries moving across their lacquered surfaces, Chanel talked of the stories depicted in their folding panels. “I see doors opening and knights setting off on horseback,” she told Claude Delay, a close friend and the writer of her 1974 biography.

They also formed a sensational backdrop for her interiors. “The rooms were dark,” says Hamish Bowles, editor-in-chief of World of Interiors, recalling visits to Chanel’s last apartment, which remains as she left it in the rue Cambon in Paris. “But the luminosity of the screens brings an extraordinary glow, and the spaces feel cosy.”

Though made in China in the Kangxi period (1662-1722), these highly decorated screens were misnamed for the spot from which they were shipped to Europe — India’s Coromandel coast — in the late 18th century. Like porcelain, they tell a tale of colonialism and trade. Now in an exhibition at the Prada Foundation in Milan, visitors can find screens of all kinds, including a stunning Coromandel from the late 17th century — a 12-panelled piece in lacquer, oriental wood and paper that depicts the birthday celebrations of an unnamed important man.

The exhibition is called Paraventi, the Italian for “screens”. It translates as “wind break”, as screens were devised in China — then adopted by the Japanese — both to protect people from draughts indoors and to create divisions outdoors. A 17th-century Chinese painting in the accompanying catalogue shows one dividing a courtyard: aristocrats party on one side, servants work on the other.

Miuccia Prada, who is the foundation’s president, has long been intrigued by these decorative objects. “They have a dual nature as an artistic and functional object,” she says in the catalogue’s introduction. In 2016, she asked the foundation’s team to start researching this under-investigated category (the last major exhibition of folding screens was in Washington DC in 1984).

By the time Nicholas Cullinan — who is also director of the National Portrait Gallery — came on board several years later to curate the show, information on 300 exceptional examples had been assembled. “A whole history,” says Cullinan, “that had not been previously put together.”

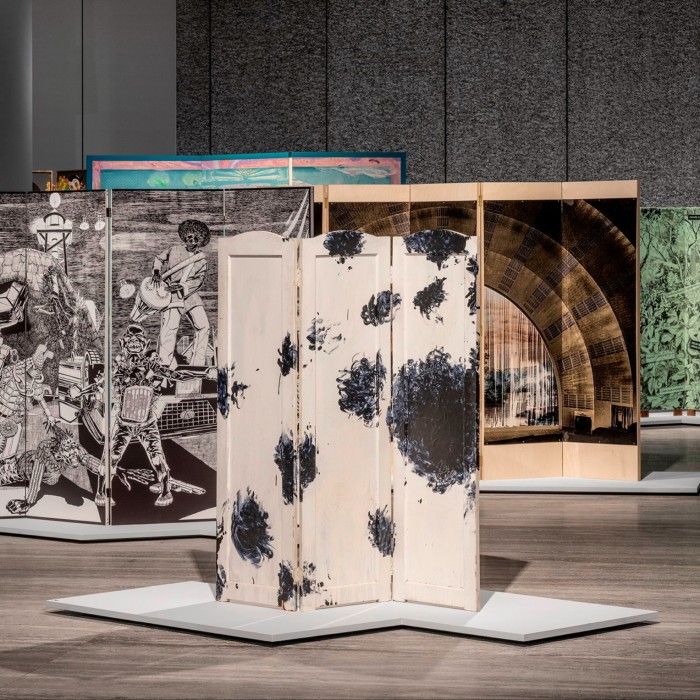

He has chosen to show 53 screens, from early Chinese and Japanese versions to those by designers including William Morris, Josef Hoffmann and Alvar Aalto. But then, discovering how many artists had fallen for the form — including Giacomo Balla, Yves Klein, Picasso and Cy Twombly — he commissioned a further 17 from contemporary artists including William Kentridge, Kerry James Marshall and Goshka Macuga, who has created a three-part concertina bookshelf loaded with books from China and Taiwan; Russia and Ukraine; and Israel and Palestine.

The hybrid nature of screens means they are both artwork and furniture; an impermanent object that can be used to manipulate architectural space. It’s hard not to see Irish architect/designer Eileen Gray’s example from 1925 — composed of gleaming interlocking black lacquer blocks — as a piece of sculpture.

“They blur the traditional hierarchies of the arts,” says Miuccia Prada. They appealed to the Bloomsbury group for that very reason: there is a fine Omega Workshop model by Duncan Grant from 1913, with a male and female figure carrying a pail of milk, which has been borrowed from Vanessa Bell’s bedroom at Charleston.

Cullinan has created groupings in the ground-floor gallery, encouraging visitors to see queerness, or gender issues, or colonial concerns in the pictorial content. The individual screens sit inside a complex scenography of curving clear acrylic and grey fabric walls designed by the Japanese architects SANAA, which itself sits inside the glass and aluminium gallery designed by the Dutch architecture studio OMA — an architectural matriochka.

Upstairs, a landscape of objects unfolds through the space. There is the stately Coromandel and a gold-leafed Japanese work covered in a flurry of coloured fans. An early work by Francis Bacon, made when he was still a decorator in the 1920s, shows an eerie combination of ghostly figures and columns. “He was desperate to put that period behind him,” says Cullinan, thinking his work on interiors would “get in the way of a future career as a serious artist”.

The Hockney depicts the joys of a stay in the Caribbean while the Le Corbusier screen, made for his Cité Radieuse housing in Marseille, demonstrates his modular architectural thesis in panels of solid black, yellow, green and grey.

Screens were popular in Britain from the 1870s to the 1930s but are rarely used in interiors today, no longer needing them to protect us from draughts or for modesty in the presence of servants. “It’s hard to include them in a scheme,” says the New York-based interior designer Rafael de Cárdenas. “Though we have hung a Japanese screen on a wall in one project, which is probably sacrilegious.”

However, Alex Lamont, a British creative director based in Thailand, makes them in finishes including lacquer, eggshell and straw marquetry. “I like them, and the way they create layering in a room without blocking things off completely,” he says. Lamont receives orders for around 12 screens a year.

They also come up in auction sales. Those by the great 1920s French masters, such as Jean Royère and Jean Dunand, can reach prices of more than £100,000. An exquisite example by Jean-Michel Frank in straw marquetry from the collection of the fashion designer Reed Krakoff made $82,000 in June 2022 at Sotheby’s in New York.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Cullinan has fallen under their spell. “I didn’t intend to buy one for myself, and then I saw one in a vintage shop in Petworth,” he says. A folding screen entirely in glass, it could date from either the 1930s or 1960s. And like Chanel’s beloved Coromandels, it lights up the room.

“Paraventi: Folding Screens from the 17th to 21st Centuries”, Prada Foundation, Milan, until February 22 2024; fondazioneprada.org/project/paraventi

Find out about our latest stories first — follow @FTProperty on X or @ft_houseandhome on Instagram