Born on April 18, 1889, in Remagen am Rhein into a Catholic family, Karl Nierendorf was educated in Cologne. He worked as a banker before World War I, but his career was disrupted in 1913 by the social upheaval in the Weimar Republic. One of his acquaintances, an art collector, introduced him to the Swiss-born German painter Paul Klee who persuaded him to attempt a career as an art dealer. The two would remain close. When Klee died in June 1940, Nierendorf published Paul Klee Paintings Watercolors 1913 to 1939 (New York: Oxford UP, 1941) as a tribute and an act of friendship.

Born on April 18, 1889, in Remagen am Rhein into a Catholic family, Karl Nierendorf was educated in Cologne. He worked as a banker before World War I, but his career was disrupted in 1913 by the social upheaval in the Weimar Republic. One of his acquaintances, an art collector, introduced him to the Swiss-born German painter Paul Klee who persuaded him to attempt a career as an art dealer. The two would remain close. When Klee died in June 1940, Nierendorf published Paul Klee Paintings Watercolors 1913 to 1939 (New York: Oxford UP, 1941) as a tribute and an act of friendship.

In 1920 Karl and his younger brother Josef began a career in the art trade and they established a pre-war reputation for championing work of the Expressionist group Der Blaue Reiter (Blue Rider). The brothers organized modernist exhibitions, lectures, concerts and film screenings.

In 1920 Karl and his younger brother Josef began a career in the art trade and they established a pre-war reputation for championing work of the Expressionist group Der Blaue Reiter (Blue Rider). The brothers organized modernist exhibitions, lectures, concerts and film screenings.

Described as both a faithful patron of artists and an astute businessman, Karl Nierendorf remained indefatigable in promoting the avant-garde throughout his nearly thirty-year career as a dealer, first in Berlin and later in Manhattan. He played a significant role in the migration of European modern art to New York.

From Cologne to Berlin

Karl and Josef Nierendorf opened their first gallery in Cologne in 1920. The brothers specialized in Expressionist watercolors and drawings. In 1923 they moved their exhibition space briefly to Düsseldorf, before settling in Berlin.

Having taken over J.B. Neumann’s Graphisches Kabinett following the latter’s departure for New York, the brothers renamed the establishment Galerie Neumann-Nierendorf. Located at 32 Lützowstrasse in the vicinity of prominent dealers such as Alfred Flechtheim and Paul Cassirer, their firm presented itself as the main promoter of modernist art.

In 1933 Neumann and Nierendorf dissolved their association and the gallery was renamed Galerie Nierendorf. The onset of the Great Depression combined with the rise of fascism badly affected all those promoting contemporary art in Germany. Nazi hatred of Modernism made it increasingly difficult to organize exhibitions or even display paintings.

The tense atmosphere took its toll on Karl Nierendorf who, in 1934, was struck by a heart attack. In the spring of 1936 he took a long break in the United States, making stops in New York and Los Angeles. His doctors had advised him that the sea voyage might improve his health, but the journey also offered him a chance to explore the American art market. Josef remained in Germany to maintain the operations of the Berlin gallery until it was forced to close in 1939.

Banned Art

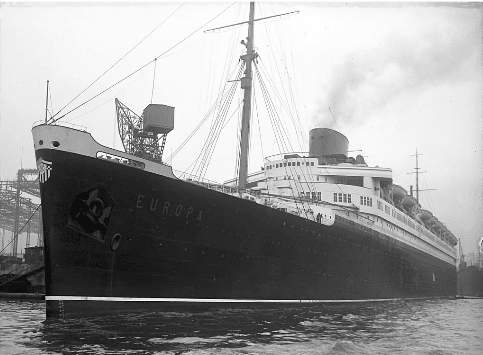

Karl sailed from Hamburg to New York on the “Blue Riband” liner SS Europa of the Norddeutscher Lloyd (NDL). On board he met Elfriede Fischinger, wife of avant-garde filmmaker and painter Oskar Fischinger who had won fame for creating the extra-terrestrial special effects in Fritz Lang’s Frau im Mond (Woman in the Moon), one of the first science fiction films to hit the screen in 1929.

Karl sailed from Hamburg to New York on the “Blue Riband” liner SS Europa of the Norddeutscher Lloyd (NDL). On board he met Elfriede Fischinger, wife of avant-garde filmmaker and painter Oskar Fischinger who had won fame for creating the extra-terrestrial special effects in Fritz Lang’s Frau im Mond (Woman in the Moon), one of the first science fiction films to hit the screen in 1929.

As the Nazis condemned his work, Oskar had accepted a contract from Paramount Studios and preceded his family to Hollywood. Forty-two paintings by artists deemed “degenerate” by the Nazis also arrived in the United States ahead of Nierendorf, hidden in Fischinger’s household effects that Paramount had shipped from Germany. Modern art was exiled to the United States.

Sensing new opportunities in a politically open environment, Karl did not return to Berlin and decided to settle in Manhattan. In January 1937 he opened the Nierendorf Gallery at 20 West 53rd Street. Later that year, he found new premises amid the bustling gallery scene on East 57th Street. His ambition was to introduce German experimental art to an American audience.

In Manhattan, Nierendorf joined a growing community of émigré artists and art dealers, including J.B. Neumann and Curt Valentin. He was reunited with several artists he had promoted in Germany who had moved to New York following the Nazi attack on modernist artists. Josef Scharl exhibited regularly at his gallery as did Lyonel Feininger, one of the pioneers of Bauhaus.

Nierendorf felt strongly that the migration of artists and dealers from Europe provided a unique opportunity for the re-creation of modernist art under new conditions. We can develop a very special atmosphere here, he suggested in the autumn of 1937 to Katherine Sophie Dreier, co-founder of the Société Anonyme (America’s first “museum of modern art” at 19 East 47th Street), the “future of culture and intellectual development lies in America.”

Group exhibitions like “Unity in Diversity” (November 1942) and “Gestation-Formation” (March 1944), emphasized that Nierendorf was keen to blend works of the European and American avant-garde. He applied artistic standards only. Considerations of nationality, gender or creed never played a part in his promotion of artists. Karl was one of those exiled dealers who put New York at the center of the art world away from Paris and Berlin. Manhattan’s 57th Street replaced Montmartre.

In the autumn of 1945 his gallery launched the landmark exhibition “Forbidden Art in the Third Reich.” It featured the work of artists who had been persecuted in Nazi Germany leading to the closure of avant-garde art galleries in Berlin, Munich and elsewhere. The show created shock and excitement. Many art critics shared the observation that “what Germany has lost, the United States and the world have gained.”

Rebay & Guggenheim

Hilla Rebay (von Ehrenwiesen) was born into a minor aristocratic family in Strasbourg, Alsace, then part of Imperial Germany. In 1908 she began formal art studies in Cologne and a year later enrolled at the Académie Julian in Paris, a private and female friendly school for art students. The institution was also open to foreign (mainly American) students.

Hilla Rebay (von Ehrenwiesen) was born into a minor aristocratic family in Strasbourg, Alsace, then part of Imperial Germany. In 1908 she began formal art studies in Cologne and a year later enrolled at the Académie Julian in Paris, a private and female friendly school for art students. The institution was also open to foreign (mainly American) students.

In 1910 she traveled to Munich to study at the progressive Debschitz-Schule which maintained links with the city’s emerging modernist movement (Ernst Ludwig Kirchner was a former pupil; Paul Klee had been a member of staff, although briefly).

Back in Cologne in 1912, she visited a traveling exhibition of Futurist artists which made a deep impact. The experience would influence her own creative work and her acquisition policies in a later capacity as a collector and curator. In 1915, with World War I raging, she traveled to Zurich, a hub of cosmopolitan creative activity. Due to Switzerland’s neutrality many artists and intellectuals had sought refuge in the city.

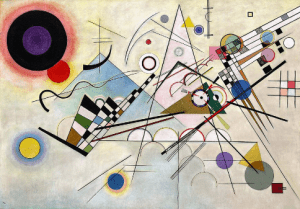

In Zurich she met fellow Alsatian artist Jean (Hans) Arp, the dynamic co-founder of the Dada movement. Arp gave her a copy of Vassily Kandinsky’s Über das Geistige in der Kunst (Concerning the Spiritual in Art), published in 1911. Three decades later, she would translate and publish Kandinsky’s essay on behalf of the Guggenheim Foundation.

Her relationship with Arp ended in the spring of 1917, but not before he had introduced her to Rudolf Bauer, a Prussian-born abstract painter who was deeply involved with Berlin’s avant-garde. Sharing similar ideas about the future direction of art, the two embarked upon a long but difficult relationship and collaboration. In the end his jealousy and misogyny became too much to bear for this talented woman.

In 1927 Hilla moved to New York, settled in an apartment of the Studio Towers atop Carnegie Hall on Seventh Avenue, and began exhibiting her work. She had brought a number of Rudolf Bauer’s paintings with her. When in 1928 she was commissioned to paint a portrait of the businessman and art collector Solomon Guggenheim, the Bauer paintings on her studio wall sparked his interest. This encounter led to a meaningful discussion on contemporary art and initiated a lifelong personal and professional relationship.

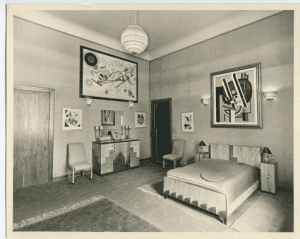

Solomon Robert Guggenheim, a mining magnate of Swiss Ashkenazi descent, began amassing a collection of non-objective art. In his obsessional pursuit of paintings, Hilla Rebay became his advisor and driving force. Using her range of contacts in Europe, Guggenheim purchased works by artists such as Marc Chagall, Robert Delaunay, Fernand Léger and Laszlo Moholy-Nagy. Guggenheim and Rebay were driven by a single shared ambition: to create a “temple of non-objectivity.”

Solomon Robert Guggenheim, a mining magnate of Swiss Ashkenazi descent, began amassing a collection of non-objective art. In his obsessional pursuit of paintings, Hilla Rebay became his advisor and driving force. Using her range of contacts in Europe, Guggenheim purchased works by artists such as Marc Chagall, Robert Delaunay, Fernand Léger and Laszlo Moholy-Nagy. Guggenheim and Rebay were driven by a single shared ambition: to create a “temple of non-objectivity.”

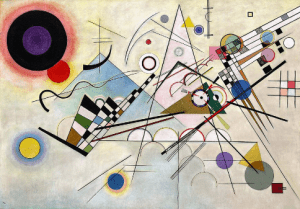

In 1930, Hilla accompanied Guggenheim and his wife Irene on a visit to Germany. The trio used the opportunity to arrange a meeting with Vassily Kandinsky who, at the time, was teaching at the Dessau Bauhaus. On that occasion Guggenheim purchased “Komposition 8” from him, the first of more than 150 works by the artist that would enter the Guggenheim Museum holdings over the years.

By 1930/1 the entire collection was housed at Solomon’s suite in New York’s Plaza Hotel and open to the public by appointment.

Guggenheim Foundation

Karl Nierendorf’s prominence as an art dealer led to collaboration with a number of museum directors who were eager to add modernist works of art to their collections. It was inevitable that he and Hilla would cross paths in Manhattan. Nierendorf was to become a vital source for Guggenheim’s acquisitions.

Karl Nierendorf’s prominence as an art dealer led to collaboration with a number of museum directors who were eager to add modernist works of art to their collections. It was inevitable that he and Hilla would cross paths in Manhattan. Nierendorf was to become a vital source for Guggenheim’s acquisitions.

The Guggenheim Foundation was created in 1937 for the “promotion and encouragement of art and education in art and the enlightenment of the public.” Its main aim was the establishment of a museum, the nucleus of which would be Guggenheim’s collection of modernist art.

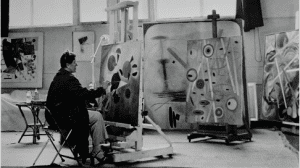

For the next two decades, Hilla zealously promoted non-objective painting, organizing exhibitions, loans and lectures on the subject. The Museum of Non-Objective Painting was opened in 1939 in temporary quarters on East 54th Street with Hilla Rebay as its first director.

In 1943, Hilla began to make plans for a permanent home for the collection and asked Frank Lloyd Wright to design a monument celebrating the spirit of modernist art. Although the site at the corner of 89th Street & Fifth Avenue was chosen as early as 1944, it took another fifteen years before the museum was finally completed.

The end of war allowed for the reopening of foreign art markets. With the freedom to travel again, Nierendorf returned to Europe in the spring of 1946. He visited family and friends and made a courtesy visit to Hilla Rebay’s relatives. He returned to New York in September 1947 in possession of more than one hundred works from the Klee estate and a large purchase from the Ernst Ludwig Kirchner holdings, partly acquired on behalf of the Guggenheim Foundation.

Shortly after his return from Europe, Karl suffered a fatal heart attack. As he had not executed a will and his recent acquisitions for the Foundation had not yet been delivered, it was decided in early 1948 that Guggenheim would purchase his entire estate from the State of New York. At a stroke, the Museum became a prominent center of European Expressionism and Surrealism.

Karl Nierendorf was a pioneering gallerist. He brought to Manhattan an unwavering dedication to modern art and succeeded in building a bridge between European artists and emerging American talent. He enabled the gradual transfer of the avant-garde from Paris and Berlin to Manhattan.

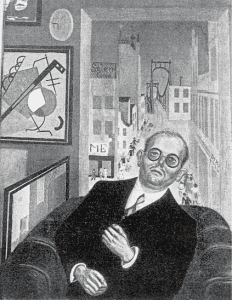

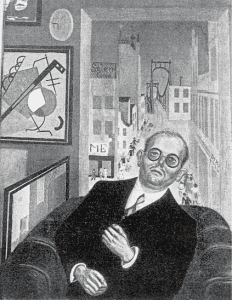

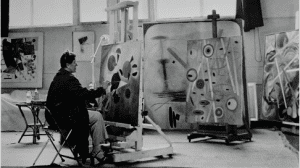

Illustrations, from above: SS Europa prior to her maiden voyage in March 1930 (Norddeutscher Lloyd); portrait of Karl Nierendorf, 1923 by Otto Dix (Unknown location; Artists Rights Society, New York); catalogue of Nierendorf’s Forbidden Art exhibition (Guggenheim Archives, New York); Hilla Rebay at work in her studio; Guggenheim’s suite in New York’s Plaza Hotel; and Komposition 8, 1923 by Vassily Kandinsky (Guggenheim Museum, New York).