In 1830, when French-Monégasque inventor Hercule Florence was 26 years old, he wrote a long entry in his diary about the future he sensed approaching.

Soon, he predicted, people from nations that had never seen each other would meet, and do so frequently.

The inventions devised by Florence and many others in the 19th and 20th centuries—from Samuel Morse’s telegraph to Thomas Edison’s light bulb—have proven this prediction, connecting us despite distance and difference. But reaching the level of technological advancement we experience today required these ever-curious innovators to push through much struggle and failure.

As an inventor, Florence, like his peers, took on the early challenges of a field that would soon be known as photography. Unlike others, he limited his use of the camera obscura to his early experiments. The camera obscura is a device that projects an upside-down and reversed image of the external world onto a flat surface through a small hole. He was looking for a less expensive and involved method of printing than those available at the time. For a few decades, Europeans had been making images appear on chemically sensitized surfaces through exposure to light, but no one had yet figured out how to keep that image in place, preventing it from darkening over time.

Unlike contemporaries who worked on this and other issues, Florence traveled to South America, inspired by his reading of Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe. He found employment in Brazil, and it was there that he responded to an ad and was hired as an illustrator and draftsman for a scientific expedition. Though he was far from Europe, where news of progress and breakthroughs would have reached him more easily, he still managed to create images that have survived to this day.

Portrait of Hercule Florence

Photo: Courtesy Instituto Hercule Florence

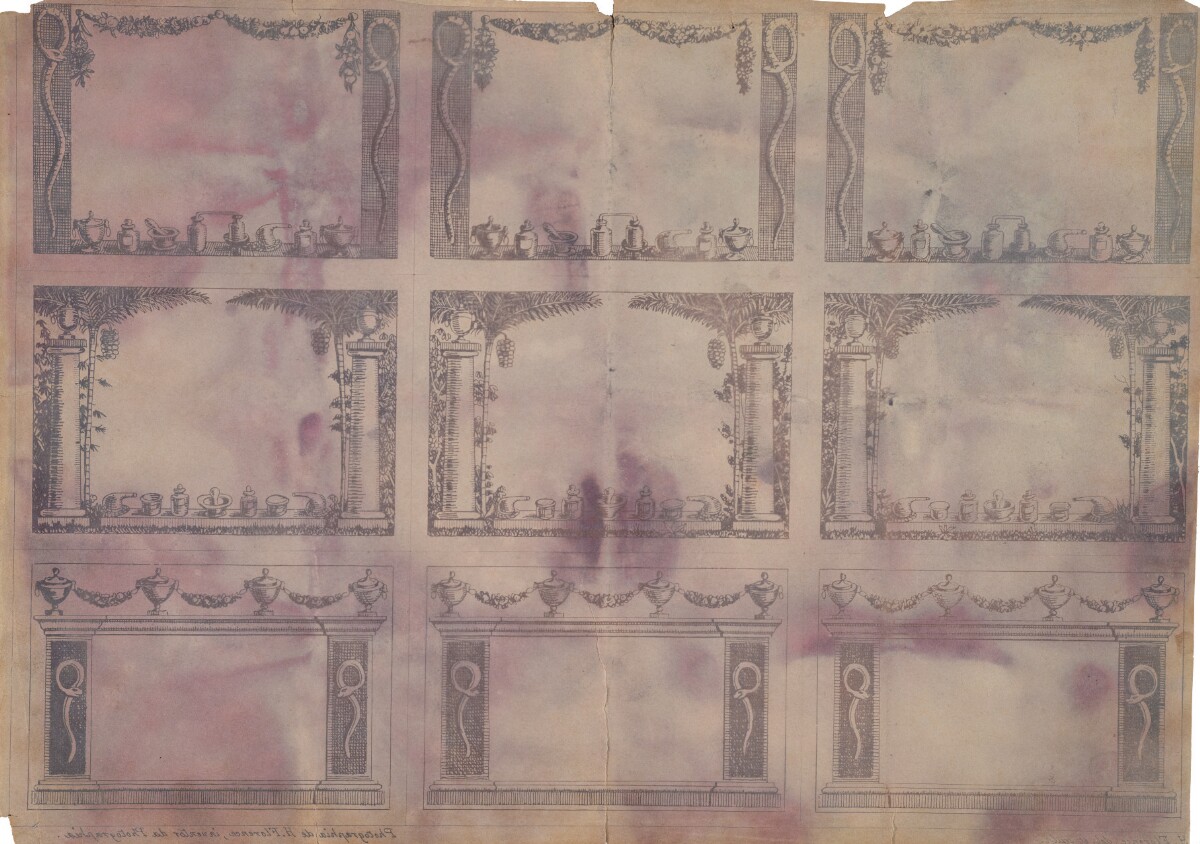

Pharmacy labels created by Hercule Florence

Photo: Courtesy Insituto Hercule Florence

Florence and his generation birthed and rapidly developed photography as a medium, inventing numerous photographic methods. For Florence, a person of wide-ranging interests, photography would only be a brief pursuit, but he didn’t leave the field behind without first making his mark. He named his invention “Photographie,” a word he coined that derives from two Greek terms that together translate as “drawing with light.”

Saving the Early Art Form

Early chemical photography used sunlight for exposure and varied development techniques, making this a complex and time-consuming endeavor. Nonetheless, it set the stage for the emergence of more convenient and accessible photographic processes that came into wide use during the 19th and 20th centuries—including those enabled by the Kodak Brownie, a portable, affordable camera that brought photography to the masses.

How photographs are made has changed drastically over the last 200 years—from capture on a chemically prepared surface to digital processes—and with this change, the number of images made each day has increased exponentially. According to 2023 Phototutorial data, five billion photographs are taken each day worldwide, and the average smartphone user keeps 2,100 pictures on their phone.

The comparatively small number of existing photographs from the 1800s makes them valuable, both as records of a way of life gone by and as examples of processes now only used by a handful of hobbyists, conservators, artists, and researchers.

Scientists at the Getty Conservation Institute (GCI), observing a shift in the availability of materials necessary for chemical photographic processes, began to gather samples of these supplies in the early 2000s. Since then the GCI has compiled a chemical photography reference collection, researched and published on the major historical chemical photographic processes and their variants, and studied examples of the processes in collections around the world.

These efforts serve the goal of better understanding what early chemical processes and techniques involved, so that examples of photographs from this era might be better cared for and appropriately displayed—thereby preserving them, and what they picture, for generations to come.

Thrifting and Convening

When Art Kaplan, who trained as a biochemist, joined the GCI to work on early photographic processes, he had some idea of what awaited him. “To me, photography was color and black and white,” he says.

He thought he could quickly grasp what he would need to know to do his job, but soon learned there was much more to it. “If we’re talking about processes and variations of the processes, there are a couple hundred. That’s a lot of chemistry.”

All that chemistry has kept him busy for nearly 20 years. Getty researchers working in this area aim to enhance the understanding of historical techniques, develop conservation strategies, and ensure the long-term preservation of valuable photographic collections.

Whenever Kaplan travels, he looks for local flea markets or pawnshops, having found interesting items to study in these places. While perusing, he keeps an eye out for any images that look unique or different from those he usually comes across, or that might represent a particular photographic process.

“I’ve purchased Wothlytypes,” Kaplan says, referring to pictures made using a silver-based photographic process that also utilizes uranium. This method was never widely taken up, and so examples of photos made using it are rare.

In 2022 Kaplan joined an international team of scholars, researchers, and scientists at the University of Évora in Portugal to study three of Florence’s surviving photographs. The research included analysis of the prints to determine their chemical makeup, the composition of their paper supports, and any chemistry indicating how the images may have been stabilized or fixed.

Findings to date, Kaplan says, show that the prints exemplify two different processes, one based on silver, the other on gold.

Because the GCI’s in-house science laboratories are currently under renovation, Kaplan hasn’t had the chance to duplicate Florence’s processes. He’ll take this next step once he has a functioning lab and access to the chemistry and a chemical hood, as well as to a dark space with sinks and water.

Though precise dating of Florence’s images is not possible with the tools currently available, researchers believe they are among the earliest in the world to have survived to the present day.

A Researcher’s Treasure Trove

In collaboration with Carolyn Peter, assistant curator of photographs at the Getty Museum, Kaplan has recently studied early images by Hippolyte Bayard, a contemporary of Florence’s who developed the art over four decades.

Getty houses more than 200 of Bayard’s images—self-portraits, pictures of sculptures and buildings, photographs of other people—many of which came to the Museum pasted into a large album. To exhibit these prints, Peter needed to know if they could tolerate gallery conditions. She also wanted to verify the chemical recipes included in some of the images’ inscriptions. Kaplan and Getty Museum conservators Sarah Freeman and Ronel Namde ran tests to answer these questions.

Most of the Bayard photographs in Getty’s collection are salted paper prints, which were made by coating paper with light-sensitive silver salts. Some are direct positives— Bayard’s best-known process, one that produced unique images without a negative.

The information gathered by scanning several of Bayard’s photographs with specialized equipment has allowed Peter and her collaborators to tell a fuller story of Bayard’s work and to better understand his place in the development of photography in the 1830s and ’40s. Until the analysis was performed, for instance, it was not known whether the process Bayard had described in a sealed letter from 1839 corresponded to one or both of the images he had included with the letter.

The research also helps prove that in 1839 Bayard was already experimenting and coming up with processes that were different from those of two other major figures working at that time: Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre and William Henry Fox Talbot.

Given the results of this research, showing which photographs can be displayed for the public and broadening the narrative concerning Bayard’s process, Peter is co-organizing an exhibition of Bayard’s work that will open at Getty on April 9, 2024.

What’s Next

Peter wants to continue testing Bayard’s recipes. It is known now that “there is some correspondence to the inscriptions”—those notes included alongside Bayard’s photographs in the album as it came to Getty—“and what’s actually in the photographs that we tested, and that’s really exciting,” Peter says. This proves her hunch that Bayard was, at the very least, involved in the album’s assembly.

This clarity about the album’s construction is one outcome of Kaplan’s research into Bayard’s photographs. His broader work with these early processes has helped to broaden the historical narrative about who invented the medium. The Getty Research Institute (GRI) has also been doing work in this area, but with an eye toward the future.

The GRI recently introduced a new generation to the importance of photography conservation by holding the first iteration of a workshop for undergraduate students from historically Black colleges and universities, during which attendees were able to work with the Johnson Publishing Company (JPC) archive. JPC, once the largest African American–owned publisher, founded Jet and Ebony magazines. Its archive of more than four million photographic prints, slides, and negatives, as well as other materials, is now owned by a consortium that includes Getty.

Kaplan participated in the workshop, sharing his own experiences in conservation over the last two decades. He will continue to teach at this and future seminars, take on research in partnership with others in the field, and search for more of those unique photographs as he travels.

There’s always the chance he’ll stumble across an example of a process not yet well known, one he’d be happy to share with the conservation world.

“Whenever I see something I don’t recognize or understand, I feel a rush of excitement and immediately start pondering what its analysis might show me,” Kaplan says.