Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The Netherlands of the 17th century and its so-called Golden Age of painting is, as Benjamin Moser observes in this fascinating, elusive yet often frustrating book, fertile ground for writers. The period stretching from the foundation of the Dutch Republic in 1588 to the Franco-Dutch war of 1672 saw this tiny state lead Europe in establishing a corporate maritime empire, revolutionising science with the study of microscopy, optics and horology, and in the process creating the conditions for an extraordinary group of painters to portray everyday urban life with a meticulous and previously unimaginable realism.

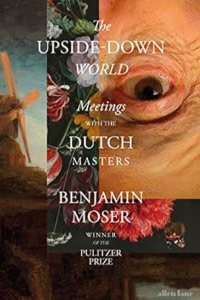

It is a time and a place that is easy to imagine thanks to its artists and exhaustively documented by its bureaucrats, yet with sufficient mysterious gaps to invite the writer to fill in its tantalising “what-ifs”. Tracy Chevalier mined the household of Vermeer in her bestselling novel Girl with a Pearl Earring, and more recently Laura Cumming wrapped her deeply personal memoir, Thunderclap, around the art and sudden death of Carel Fabritius in the gunpowder explosion that devastated Delft in 1654. Fabritius’ masterpiece “The Goldfinch” also lies at the heart of Donna Tartt’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel of the same title. For Moser — the Pulitzer Prize-winning biographer of Susan Sontag — to turn to the art and history of this period is a surprise, even if one that does not wholly convince.

Moser’s interest was born of love. Aged 25, he moved to the Netherlands to pursue a love affair and a writing career, and fell in love with the art of Rembrandt, Vermeer, Hals and the 15 other artists featured in The Upside-Down World. It is in many ways highly conventional in offering a chapter to each painter, and can be read as Moser introduces it: a deeply personal, lyrical and philosophical introduction to the Dutch masters.

He looks deeply and reads widely, with fascinating insights and revelations: Rembrandt’s “faith in darkness”; Fabritius and his enigmatic self-portrait and “View of Delft” as “the unanswered question of Dutch art”, bridging Rembrandt and Vermeer; the exuberance of Hals, “an exile from time itself”, painting beyond the conflict of the times in his famous group portraits of the wealthy Dutch burghers of Haarlem currently on show at the National Gallery in London, in which there “are no dull passages; everything is climax”.

Jacob van Ruisdael, the period’s greatest landscape painter of windmills, castles and, well, the sky, is seen as reinventing the whole genre of northern landscape painting. Moser sees his landscapes set against the flat anonymity of the Low Countries, and Ruisdael’s subjects are, Moser suddenly realises, clouds, where the skies are “like the vault of a cathedral”, and the flat land incidental.

The author is honest enough to describe some early Vermeers as “weird” and “ugly”, while using Marcel Proust’s encounter with the “View of Delft” in 1902 as “the most beautiful painting in the world”, and Van Eyck to offer a gorgeous description of how at his best Vermeer’s “pearlescence” traps light, but how, like his picture, the artist “seems to dissolve the closer we get to him”. After Vermeer, Moser notes, painting did not have to be about grand historical events and people: it could be about anything, from a maid pouring milk to a yellow stone wall.

For all his deft observations and limpid writing, Moser isn’t always able to sustain his acute insights or enthusiasm, nor able to communicate why we need this book now, and how it makes us rethink this remarkable yet diverse collection of artists. The chapters on Albert Eckhout’s paintings of indigenous Brazilians and the still life paintings of Rachel Ruysch (the only woman among Moser’s “masters”) are not so assured, as though Moser is less comfortable addressing gender and colonialism.

At times there is an attempt to over-interpret, as in a fruitless gay reading of Ruisdael, all the more frustrating after such adroit observations about his painting. There is a fixation on “charisma” as a recurrent feature of many of the artists, but it is never pinned down.

Perhaps this is deliberate. In writing on Hals, Moser reflects that we are “not really looking for answers”, and that “truth can be glimpsed only in fragments”.

Moser himself flits in and out of the narrative, a shadowy presence like one of the distant figures in a Ruisdael landscape. At one point he describes being in Haiti, wondering why he is writing on Jan Lievens in the midst of such poverty; he buys a dog in lockdown and walks it near Utrecht; he takes his father to the trial of the Serbian strongman politician Slobodan Milošević in The Hague (2002-06) and reflects how in the time of Vermeer, the Netherlands was like Bosnia in the grip of civil war.

Where Cummings’ Thunderclap uses Dutch art to sharpen memoir, in The Upside-Down World painting and memory hang suspended, never quite holding the conversation that Moser seems to want. It will be interesting to see where this clearly talented writer goes next.

The Upside-Down World: Meetings with the Dutch Masters by Benjamin Moser, Allen Lane £30, 400 pages

Jerry Brotton is the author of ‘The Sale of the Late King’s Goods: Charles I and his Art Collection’

Join our online book group on Facebook at FT Books Café