Was Robert Musil right with his sardonic quip “There is nothing in this world as invisible as a monument”? Cenotaphs, triumphal arches, bronze effigies frozen in time and space: we walk right by, barely noticing them. They may commemorate events of profound human cost, but, as physical relics, they seldom touch us. Now and then, a quiet presence of stone and light can move us: Maya Lin’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial; or Daniel Libeskind’s Jewish Museum, in Berlin; or the Lincoln Memorial, with Daniel Chester French’s serene image of the seated President. But such works are in the minority. More often, monuments fail to achieve their goal of prodding us to reflect. As Musil writes, in his “Posthumous Papers of a Living Author” (1936), part of the problem may be a monument’s very permanence: “Anything that endures over time sacrifices its ability to make an impression.”

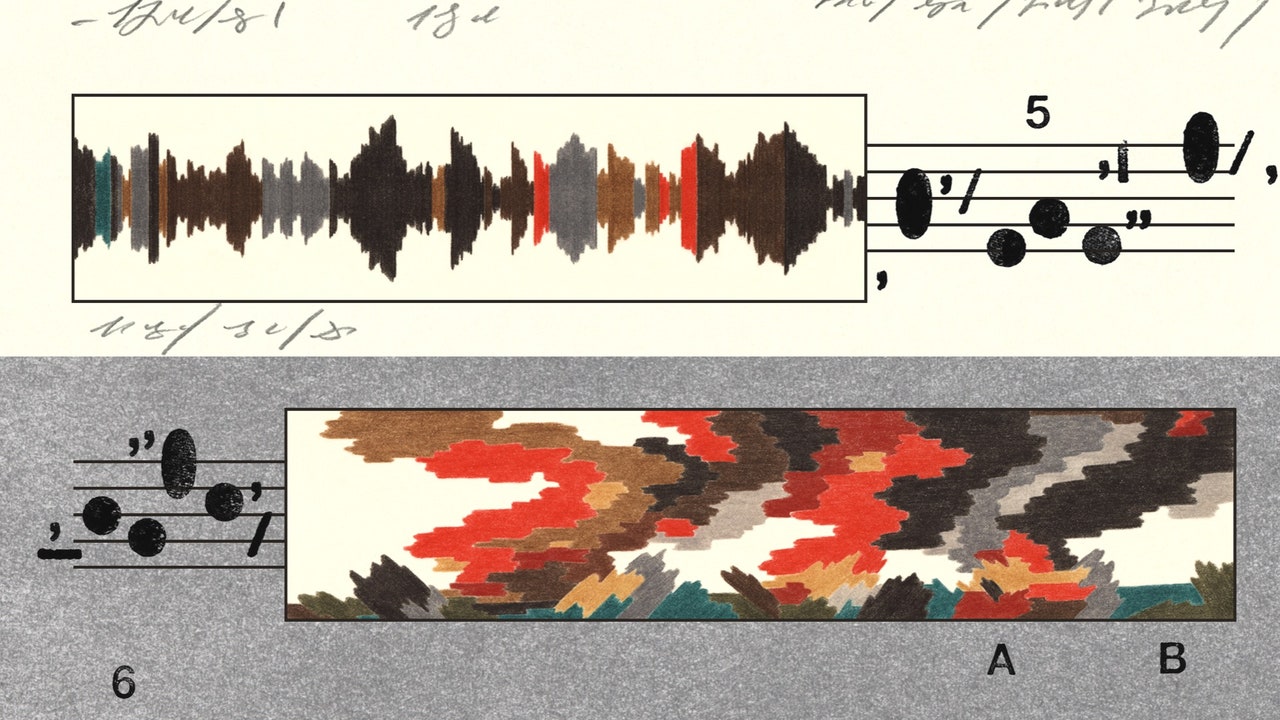

Musil was discussing physical monuments, but there are other kinds, as Jeremy Eichler shows in “Time’s Echo” (Knopf), an examination of how music can function as a vehicle for collective memory. “Sound is too visceral a medium, too penetrating of the senses to be naturalized like stone,” Eichler writes. “When music floods a room, there is nowhere to hide.” Gravely lyrical, the book is a work of vast historical scholarship and acute musical insights, and Eichler, the chief classical-music critic of the Boston Globe, is not shy about his mission, which is to demonstrate that what Thomas Mann called music’s “spoken unspokenness” gives it a unique power to memorialize in a way that engages our emotions. Eichler makes his case by scrutinizing four key mid-century works that attempted to address the catastrophe of the Second World War: Richard Strauss’s “Metamorphosen,” Arnold Schoenberg’s “A Survivor from Warsaw,” Dmitri Shostakovich’s Thirteenth Symphony, and Benjamin Britten’s “War Requiem.” Each, he claims, functions “as a carrier of memory for a post-Holocaust world.” Approaching his task “with the ears of a critic and the tools of a historian,” Eichler details the geneses of these works and their receptions, their composers’ wartime experiences, and the wider history of the war and of the Holocaust.

Each of these “intensely charged memorials in sound,” Eichler writes, is “a prism through which we ‘remember’ what was lost.” That’s a weighty burden to place on any piece of music, not to mention on a listener. There are many for whom nonnarrative works—Bach’s Goldberg Variations, say, or a Beethoven string quartet—represent, in their very abstraction, the epitome of pure musical meaning. For such people, this kind of musical memorializing is bound to seem uncomfortably freighted—art with an agenda, relying on extra-musical cues for its significance. Not everyone wants a musical experience to conjure images of violence and grief. Eichler seems to acknowledge this, at one point posing the question “Should genocide really be the stuff of a night out at Carnegie Hall?”

In 2001, shortly after the September 11th attacks, I found myself confronting similar questions when the New York Philharmonic asked me to compose a work to honor the victims who died in the World Trade Center. I was initially reluctant to accept. It seemed too soon: How could one create music to “commemorate” a public trauma that the nation was still processing? At the same time, it felt wrong to say no. Surely a composer ought to be able to respond to a public need; if firefighters and first responders were risking their lives at Ground Zero, the least I could do was answer the call. The resulting work, “On the Transmigration of Souls,” was agonizing to compose, not just because I spent months meeting with grief-stricken families and reading their accounts but also because I found it nearly impossible to fix on a voice for the piece. The media was still hectically recycling images of the catastrophe, to the point where any real meaning had been leached from them. In the end, I made what I termed a “memory space”—a mostly quiet piece for orchestra and a chorus of adults and children which incorporated prerecorded sounds of the city and the murmured recitation of names and phrases from missing-persons signs. The piece had its première on September 19, 2002, almost exactly a year after the event that prompted it—paired with Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, that most famous of Enlightenment narratives, which carries its listener from minor-key struggle to major-key victory.

There is no such victorious exultation in the four works that Eichler examines. Two address the Holocaust specifically: Schoenberg’s “A Survivor from Warsaw,” a blunt and graphic piece for narrator, men’s choir, and orchestra, relates the experiences of a survivor of the Warsaw Ghetto in a concentration camp; Shostakovich’s Thirteenth Symphony opens with a setting of Yevgeny Yevtushenko’s poem “Babi Yar,” remembering the Nazis’ massacre of Jews in Kyiv, in 1941. Strauss’s “Metamorphosen,” scored for twenty-three solo strings, is the only one of the four pieces that has no text, and is the most inward-looking, unfolding as a seamless half-hour lament. Britten’s “War Requiem,” by far the longest, is a huge cantata of public grieving.

It’s difficult today to imagine a composer of classical music commanding the kind of attention that these four enjoyed. Shostakovich was only nineteen when his First Symphony made him famous, and from then on premières of his large-scale works were significant events in the Soviet Union. Britten deliberately mined a deep vein of English experience and became one of his country’s most beloved composers. And Strauss, in Germany and Austria, was seen as the inheritor of the great lineage dating back to Bach—the living embodiment of what Eichler calls “the stupendously overdetermined relationship between Germans and music.” Only Schoenberg, whose atonal music was forever at odds with convention, remained an outlier. Yet, paradoxically, it was he, not the other three, who would emerge as the model for much of the following postwar generation of avant-garde composers.

The four composers experienced the Second World War in radically different ways. Strauss remained in Germany and Austria, his reputation forever sullied by his ambivalent relationship with the Nazi regime. Schoenberg watched helplessly from his home in Los Angeles, having fled Europe in 1933, when Hitler came to power. Shostakovich was a volunteer firefighter during the siege of Leningrad. His Seventh Symphony, written in the midst of the conflict, essentially live-streamed the city’s resistance to the German assault. Britten, a pacifist, left England for America shortly before the outbreak of war (a decision some of his compatriots never forgave) but returned in 1942; registering as a conscientious objector, he was exempted from military service and spent the rest of the war working on the opera that was to make him famous, “Peter Grimes.”

Of the four, Strauss’s story is the most uncomfortable to contemplate. Achieving fame in the late nineteenth century, while still a young man, he demonstrated a Nietzschean skepticism toward the lofty Bildung ideals of nineteenth-century German art and philosophy. In contrast to the spiritually questing emotional roller coasters of his contemporary Gustav Mahler’s symphonies, Strauss’s works were the product of an artistic personality that toggled between studied irony and a bourgeois sentimentality seemingly custom-cut to Wilhelmine sensibilities. He could shock and thrill, as with his two blood-and-gore operas, “Salome” (1905) and “Elektra” (1909), but it was the plush period-piece romanticism of “Der Rosenkavalier” (1911), with its lilting waltzes and luscious female roles, that brought his popularity to its peak.

Amid the advent of National Socialism, Strauss was one of many cultural figures who found themselves performing a complex dance with the Nazis. He had Jewish family members (his daughter-in-law’s family and his grandchildren) whom he wanted to protect, not to mention Jewish friends and colleagues. He may have considered himself apolitical, but there was no escaping Hitler, who—disturbing as it is to realize—was quite possibly the most musically knowledgeable head of state ever. The Führer knew his Beethoven and his Wagner, and he maintained an almost boyish enthusiasm for opera productions that had thrilled him in his youth. Thus, for Strauss, there was no declining an invitation, in 1933, to become president of the newly created Reich Music Chamber, conceived by Joseph Goebbels as a means of purging German music of “cosmopolitan” (that is, Jewish) influences.