‘Artificial intelligence’ is a misnomer, a natural scientist admonished me at a recent summer symposium by Lake Garda in sunny Italy. Instead, I should have said ‘artificial neural networks.’ Presumably his reason for this fraternal correction was that machines do not possess real intelligence as humans do. Variants on this argument percolate on the web proclaiming that AI systems are merely advanced calculators or the equivalent of an enormous army of monkeys ferociously hitting typewriter keys and eventually producing something meaningful. At the same time, the Bah Humbugs of the sceptics are contraposed by the metaphysical promises of others proclaiming the imminent singularity: the arrival of conscious, self-aware, super intelligent and autonomous AI systems taking over the world. Often this comes, as in most books and films treating the topic, with apocalyptic fears of the not-so-far-away destruction of humanity; whilst in real life Hollywood, where movie companies regularly produce such fantasies, the more mundane fear of unemployment dominates: a future in which the robots on their own produce both the epics of their triumph and the accompanying soothing pieces of entertainment for the lesser species.

For Christian thinkers, crucial philosophical and theological concerns revolve around whether AI systems should ever be considered persons, classically defined by Boethius as individual substances of a rational nature.

The first question is thus whether an artificial construct can in some way become a substance, or if this is impossible. Thomas Aquinas seems, at first glance, to hold that they cannot, since artefacts are not naturally integrated wholes. Human persons manipulate substances such as stone, wood, and metal into accidental structures—for example, a house, which to the frustration of the homeowner tends to resolve back to the various substantial forms of its constituents. The artifact is a result of art (arte + factum), a broad spectrum of practices from the mechanical to the fine arts—in other words, culture.

However, as Michael Rota points out, this might be an oversimplification of Aquinas’ position. Rota takes the example of bread in Aquinas’ discussion of the Eucharist. Although bread is an effect of a human art, namely bread-making, the newly baked loaf has, according to Aquinas, a substantial form, because bread is a result of natural principles guided by human efforts.

The materials making up a house, on the other hand, do not by their own inherent principles form a new substantial form. Our dwellings are merely temporary configurations of parts. For a house to be a substance, it would need to achieve a stronger form of unity. Wood, stone, and metal would have to lose their substantial forms as oxygen and hydrogen do when forming water, establishing a new whole with emergent qualities superseding those of its parts.

This means that humans could make an AI system into a substance if its structure were derived from the natural processes of its parts with added forces such as heat, as in the case of bread. Possible cases would be organic or quantum computers. Without this naturally formed unity, the machine could not be a substance, at least according to a Thomist, and therefore not a person—but could it still be rational?

According to Aquinas, immaterial substances such as a soul establish concepts by abstracting ideas (forms) from sense experience. From seeing, touching, and hearing many dogs, one acquires the concept of ‘dog,’ which can be signified by many different words or gestures. An angel, on the other hand, sees ideas in an immediate, intuitive way, while a child learns what ‘dog’ is when his parents tell him that a Golden Retriever is a dog, and then again that a Doberman is a dog. In this way, the child gradually grasps some of the common qualities shared by different species of dogs, and eventually he can categorize a Pekinese as a dog without assistance. Artificial neural networks are trained in a similar way to recognize patterns and use them to ‘decide’ whether a particular image is of a cat or a dog. But do the machines, thereby, have a concept of a dog?

According to Aquinas, animals lack intellects and immortal souls, but they still have some powers of cognition and classification, if only by natural instinct (vis aestimativa). A classic example is that of sheep running when it sees a wolf. At least this level of cognition seems feasible for an advanced artefact such as AI. Moreover, if it can be formed as bread through nudging natural principles toward transformation, it would at least be a step toward personhood, even if our artificial intelligences do not have real concepts.

Still, however exciting or scary the vision of a future involving ‘living’ artificial intelligences may be, I would like to point to a more present dilemma that affects anyone working with creating, analysing, and judging cultural artefacts: how do we know that other persons actually have concepts? The simple answer is that we decide this by interpreting behaviour and its results: gestures, facial expressions, sounds, and texts. As a teacher, I do not see the concepts held by my students. I infer them from their writings and conversations. If a machine with its layered neural networks can produce similar texts or converse coherently, then the taken-for-granted relation between cultural sign (artifact) and thought is broken, and the hermeneutical burden of the teacher increases to superhuman levels. This is a huge problem for education, as it relies on judging texts, images, and electronically mediated real time dialogue, as on Zoom or Teams, as signs of understanding and reasoning.

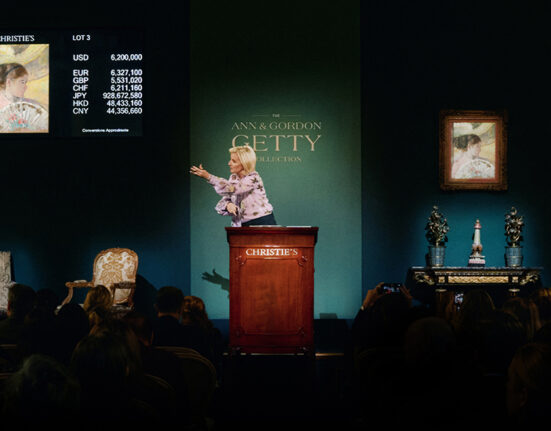

When our culture increasingly becomes a world of artefacts made by artefacts, sometimes prompted by humans, sometimes prompted by other AI systems, professors and cultural critics need to use special strategies and techniques for inferring human rationality and imagination, or give up and see texts, images, and videos as mere tools with functions. The idea of an author then finally dies.

If one instead chooses to infer the presence of rationality, then one needs to search for signals of genuine human interiority that cannot be faked. In societies where more and more human interaction and culture is electronically mediated or preformed by AI systems, this is problematic. The mediated faces or voices are not necessarily representations of actual human persons or faithful versions of them, since the signal can be manipulated in real time. Moreover, with the looming prospect of Apple’s Vision Pro, what the eyes see through the headset will be completely mediated.

My guess is that the difficulty of trusting signs of interiority will lead to the increasing importance of non-artificial forms of meaning that do not rely on signs as mere tokens of interior states. For anyone working with Christian culture in an increasingly de-Christianized Western world, this will, I believe, involve a renewed interest in sacramentality. For example, according to Catholic teaching, particular material substances must be used for the sacraments. During the medieval period, there was a petition from Norway regarding whether it was permissible to use beer instead of water for baptism—a request that was denied. Similarly, in our own time, confession may not be administered through Teams or Zoom. Physical presence is required. The Eucharistic wine must be made from grapes and not some other fruit. And so on. This is different from personal prayer, which can be done anywhere externally or internally, for persons present and absent, dead or alive.

At the same time, sacramental physicality relies on a particular logic of signs, but as communally fixed and for achieving spiritual results, not as indexes of interior thoughts or emotions. The sermon might be written by ChatGPT, and the organ played by a robot, but the minilecture or the music is not of the essence of a sacrament in the way the bread is essential to the Eucharist.

Furthermore, it is Catholic teaching that the sacraments work ex opere operato, that is by the power of the actions themselves. They are, therefore, not dependent upon the moral character or emotions of the priest, although they must be performed “in accordance with the intention of the Church.” In this way, the annexation of the relation between sign and human interiority by an intelligent artefact is resisted. The ritual action of the sacrament achieves its spiritual transformation irrespective of illusive human feelings, attitudes, and thoughts: bread becomes the body of Christ, original sin is removed, and the spirit of a man is imbued with the character of Christ in ordination. Hence, a priest is a mediator and not an artist expressing emotions or personal ideas and intentions.

What does such a development mean for Christian culture more generally? First, it calls Christians to distance themselves from a culture of individualist expression and consumption to one of ritual physicality and socially established meanings, in which spirituality instead of psychology is in focus. A sacramental culture challenges the consumption of experiences and meaning based on personal preferences. Ritualization of meaning is embodied and communal, and it involves the sacralization of place and time together with the manipulation of physical substances. A trend pointing in this direction is the growing interest in pilgrimages.

Education taking place in sterile, efficient, whitewashed rooms focused on the transfer of knowledge will easily be taken over by artefacts. The counter movement would then be education as pilgrimage, a transformative and embodied journey or education, such as a liturgy in which the full sensory spectrum is used together with ritualized actions and meanings. Rationality then has to cooperate with mystery, sacrality, personal transformation, and aesthetics.

In the same way, reading would recapture a ritual dimension of shared meaning, and art would move from the impersonal walls of galleries back into liturgical spaces where artistic individuality is not of the essence. The gaze of the tourist and of the connoisseur would then be exchanged for that of the initiated worshipper.

If Christian culture recaptures a strong sense of liturgical sacramentality in which a substance created by human art—bread—is transubstantiated into divine materiality and then ritually eaten, then the challenge posed by intelligent artefacts producing cultural signs is put into a perspective unavailable to secular modernity. The combination of spirit and concrete materiality balances the understanding of the art object as a sign of subjectivity. However, for this to become a reality, young Christian artists need to recapture principles that have become weak, forgotten, or misunderstood, such as the relation between the sacred and profane, blessings and curses, sin and grace.

Previously published in St. Stephen’s Forum, a Catholic Journal based in Bard College.