The second part of my ongoing conversation-based series on embroidery zooms in on the intricacies of Bhasha Chakrabarti and Elif Erkan’s artistic practices, both of which remain heavily influenced by feminist appropriations of textile and embroidery art. An Indian-origin Yale School of Art MFA graduate who grew up in Hawaii, Chakrabarti’s ideology is centred on notions of “mending”, repair and repurposing while critiquing the legacies of colonialism and their continued sway. I enjoy the erudite nature of her meticulous work and how she chooses her mediums and materials in order to advance her intellectual propositions in a manner that is articulate and cohesive.

Born in Ankara, Erkan currently lives in Vienna. She is one of those artists who works quietly and meditatively. You are unlikely to catch her “on the scene” or networking, and she usually sustains herself through full-time work (she’s currently a kindergarten teacher) so she can maintain integrity within her work. Erkan is currently preparing for her upcoming solo show In Bloom at The Pill in Istanbul slated for November 30, 2023. “The exhibition will have at its core Turkey in the early 2000s and its relationship to a very particular performative understanding of modernism, which will be presented by paintings that are rusted, photographs from my personal archive, marble houses on naked concrete plinths and large balls of blond hair,” she informs us.

In a conversation with STIR, both Chakrabarti and Erkan reflect on their ongoing work and how it relates to embroidery, time, feminist histories and ideas of continuity.

Rosalyn D’Mello: In a post on Instagram, you recently mentioned embroidering a sari border for a painting. Could you talk about this a bit and give some more context?

Bhasha Chakrabarti: I believe you are talking about the borders I was making/embroidering for my most recent carpet paintings. For a while now, I have been trying to push the notion of painting as a form of textile art since it is traditionally and most commonly done on cloth support—whether that be linen, canvas or jute/burlap. However, due to the gendered and colonial hierarchies of Western art, there is this large gap between what we consider to be the more “fine” art of oil painting and the more “craft” arts of quilting, weaving and carpet making. My most recent series has been about making oil paintings of carpets in museums (whether they be on the wall as artworks in the collection or on the floor as decor items) and making these paintings on jute, which is both a traditional painting support and a traditional carpet making material. I then place these on the floor as a carpet would be placed. But, of course, mine is an oil painting so displaying an oil painting on the floor is somewhat anxiety-inducing to us perhaps? In my most recent works, I’ve been blurring the boundaries further by mixing embroidery into the oil painting, specifically as a border, which can both act as a frame—pushing it more into a “painting” space—or act as a marker of a woven textile piece—pushing it into the ‘carpet’ space.

Rosalyn: Do you find yourself looking at the back of your embroidery as you stitch?

Bhasha: It’s funny to think about this because traditionally, looking at the back of an embroidery piece is a way to judge its “fineness”. I’ve been doing a project on Parsi Garas (a type of Indian embroidered sari with Chinese influences) recently and repeatedly you see mentions of how not being able to distinguish between the front and back of a section of embroidery is a testament to the skill of a craftsman. But as one of my weaving teachers once told me: “Good thing you’re an artist, because you don’t have the finesse of a craftsman.” It’s true. I don’t ever check the backs of my embroidery or even the backs and inner seams of my quilts, beyond being sure that they are structurally sound and secure. In fact, I use the backs to hide as many secrets as I can: the frustrations with the needle, the pressure of time and the unfulfilled aspiration towards craftsmanship. It’s a mess back there, but as long as I can keep moving forward, I move forward.

Rosalyn: How do you decide when a work should be painted and when it should be embroidered or whether to incorporate embroidery in your work?

Bhasha: I’m often trying to close this perceived gap between the two forms, which means the decisions can, at times, be somewhat arbitrary. Often I think of moments of “embellishment” as the perfect moments for embroidery in a painting. This is not to minimise the role of embroidery— embellishment and adornment are essential to me and to my notion of a painting. In that sense, I am perhaps more aligned with the role of the decorative in Indian aesthetics than in Western art. I also jump back and forth between painting and embroidery in order to establish a rhythmic pace of work in the studio, as the two forms have very different senses of time. The ideation time of painting is long but the execution for me is quite quick, for embroidery, it’s the opposite. I often know what I want to embroider very quickly but executing it, since I only embroider by hand, takes much longer.

Rosalyn: Explain more about your experience of time when you embroider. Is it different from quilting?

Bhasha: There is a unique experience of time when embroidering. I had actually read an article somewhere a long time ago (and then made an entire series of work on this) on the fact that because time and progress of embroidery are so hard to monitor and measure, especially in the context of women embroidering at home between household chores, 18th century European and American women could use the excuse of “embroidering together” as a way to spend inordinate amounts of time together and even cloak romantic relationships. So, there’s something really radical about the slowness of embroidering time, it’s not just lethargic. But then, of course, I think about embroidery time in the context of capitalistic production and labour and it can start feeling really violent, exploitative and fetishised. I’m thinking of brands that advertise their clothes as having taken “60,000 hours and 45 people” to embroider and it just makes me shiver. Like, how do you want to wear that after hearing that? It’s troublesome. But, as an artist working with embroidery, I have to remind myself constantly to “stay with the trouble”, right?

In terms of the second part of your question, time in embroidery is totally different for me than time in quilting. There’s two parts of stitching in quilting (when thinking about most types of quilting in the West): the first is in piecing and constructing the quilt top, which, for me, is a simultaneous process of composition and construction, almost like drawing or painting, but with the added pause of the time it takes to finalise the seams between the pieces. Then there are the stitches of “quilting” which are binding the top to the back and the batting in the middle. This process is often very much like weaving as it is repetitive, slow and difficult to measure progress with. Embroidery is somewhere in the middle of these two processes, one could say, as I am not usually “composing” the image as I am embroidering it, because I trace out the pattern to be embroidered beforehand. However, I’m also not just in an endlessly repeating process of sewing with no sense of progress, as I’m using a variety of colours, stitches and can slowly track the image forming before me.

Rosalyn: Would you say that your inheritance of embroidery as a skill and a craft and your use of it as an art form has a matrilineal legacy?

Bhasha: I think there’s something about women passing down sewing to one another intergenerationally, and not even necessarily because they “teach it” to the next generation. I think it’s something contained in the body. My parents are convinced every time they see a work of mine that it comes to me from my father’s aunt who was legendary for her embroidery. I have never even met her, but for the first four years of my life I was swaddled in a kantha [embroidered quilt] that she had made for me. So sometimes I think that I absorbed my tendency to stitch through my skin touching that quilt which she had touched for hours while wearing those sarees and then quilting and embroidering them into that kantha. It somehow makes sense.

Rosalyn: Tell me about your work Palimpsest (2019-23)?

Bhasha: Palimpsest is a kantha quilt made using old clothing belonging to me, my mother and my grandmother and scrap/fabric waste from [the designer] Rashmi Varma’s studio.

It doesn’t really have a “front” and “back” as it’s a kantha with running stitch, so both sides are meant to be similar (one to be “looked at” and one to be laid against the skin). Originally destined to become parts of sari-dresses, kurtas and skirts, these particular pieces that were snipped off, mistakenly cut or simply left behind have been carefully pieced together along with clothes worn by multiple generations of women in my family. The cloth and clothing have been layered and quilted using a simple running stitch, in the centuries-old tradition of kantha quilting from Bengal. Kanthas are crafted from old and discarded saris through countless hours of meticulous threadwork, typically done while sitting on the floor with the cloth spread out before the maker. The old saris, which are already softened and worn-down from contact with their own skin, are refashioned by mothers and grandmothers as second skins to keep their loved ones warm. This practice embodies elements of thrift, while working within economies of domesticity and intimacy. The materials used, its method of making and the mode of display of Palimpsest come together to examine, interrogate and intervene in a series of discourses around art versus craft, the alienation of labour within the luxury market, the role of sustainability and waste in fashion, and the larger divide between public and the private.

In his essay Textile Art – Who are You? (1992), Sarat Maharaj presents a quilt as an example of what the philosopher Jacques Derrida has termed an “undecidable”. Maharaj explains this as “something that seems to belong to one genre but overshoots its border and seems no less at home in another. Belongs to both, we might say, by not belonging to either.” The two genres that a quilt has historically been seen as slipping and sliding between are that of “fine art” and “craft”. Maharaj elaborates, “Hung up on a wall, framed, put on display, (the quilt) catches our attention as a statement of form, colour and texture. We soar away with its allusive, narrative force. But we never quite manage to set aside its ties with the world of uses and functions, with the notion of wrapping up, keeping warm, sleep and comfort, some feeling of hearth and home… Half-on-wall, half-on-floor, it stands/lies/hangs before us: everyday object and artwork in one go. Domestic commodity, which is at the same time the conceptual device. The quilt stands/lies/hangs before us as a speculative object without transcending the fact that it is a plain, mundane thing.”

Palimpsest embodies this ambiguity and “in-betweenness” on multiple registers. As detritus of Rashmi Varma’s studio, the fabric pieces in the work gesture towards garments intended to be worn in the public world; but when repurposed to serve as second skins, the quilts whisper into the private, domestic space of a bedroom. The very materiality of this quilt embodies both a public history, being recognisable and continuous with Rashmi Varma’s fashion brand, and yet at the same time tells an alternative story. Ultimately, of course, Palimpsest is not simply a quilt on the bed. A kantha is primarily a functional object meant to be touched and handled, but, when hanging on the wall, it becomes art to be appreciated and interpreted from a distance. As quilts displayed in a gallery, Palimpsest continues to oscillate between the public and private, between the world of exchange and the world of care in a self-reflective and yet disconcerting way.

Rosalyn: During our last conversation, you talked about embroidery being a central part of your upcoming show. Could you tell me more about that?

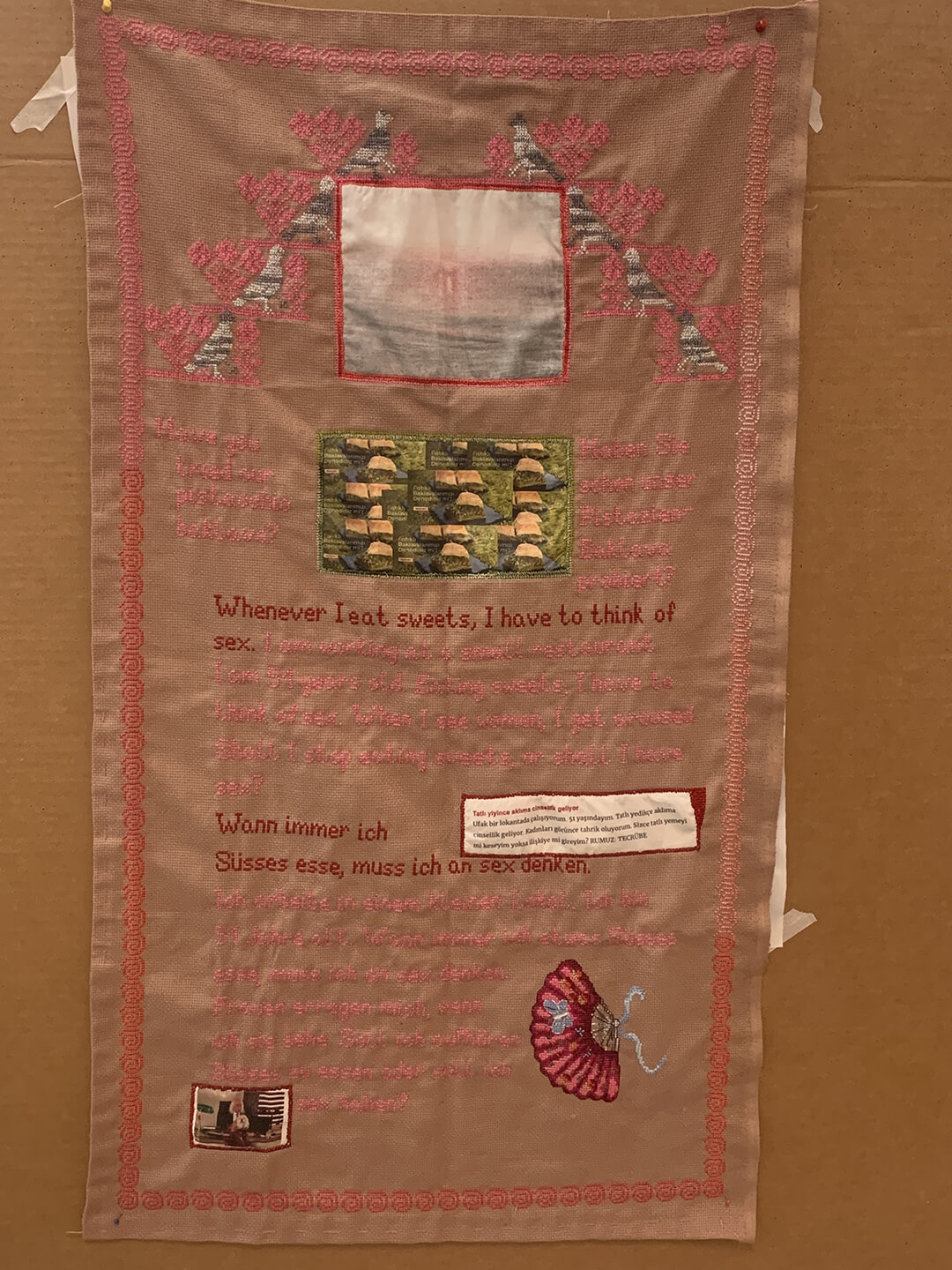

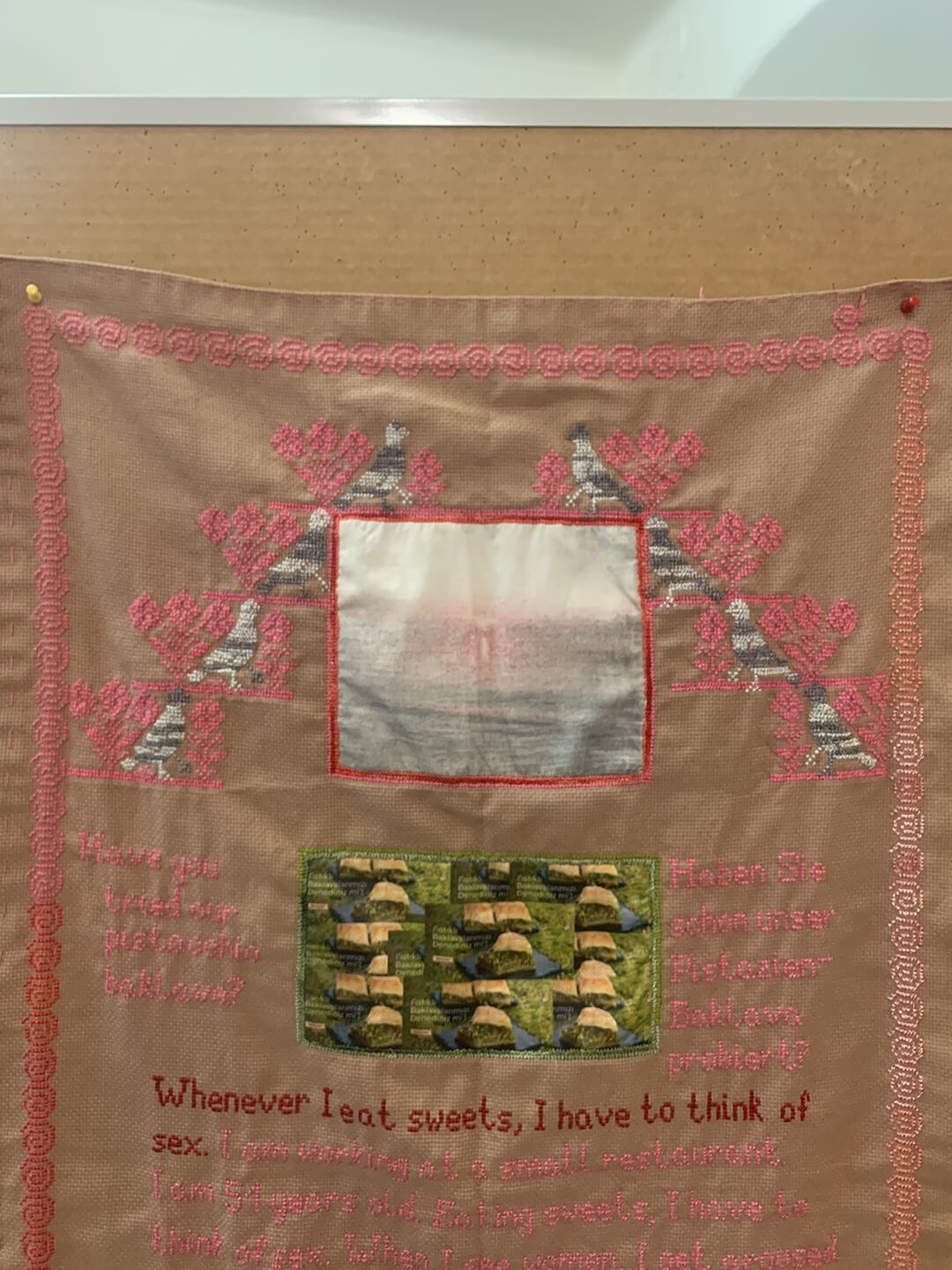

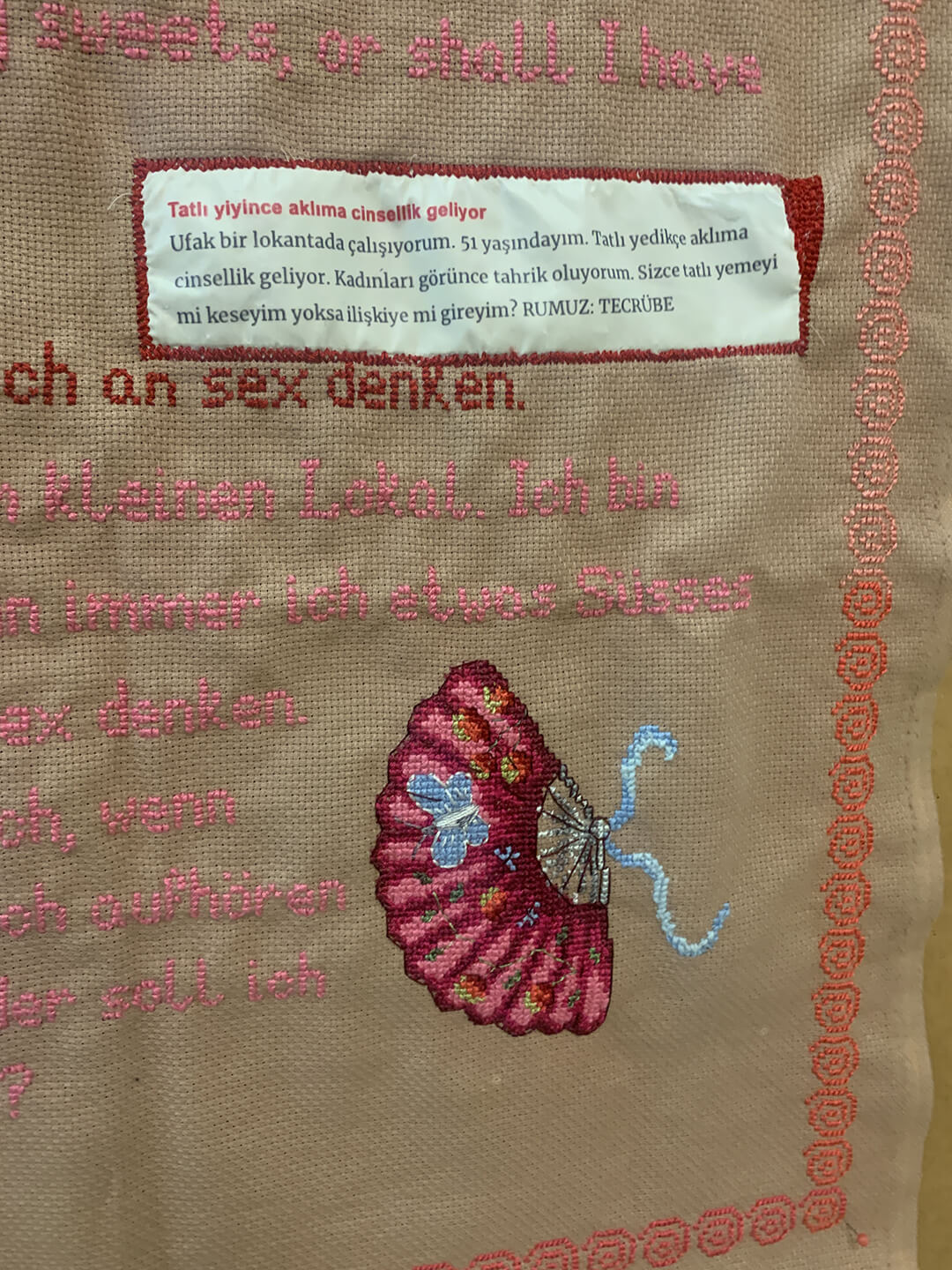

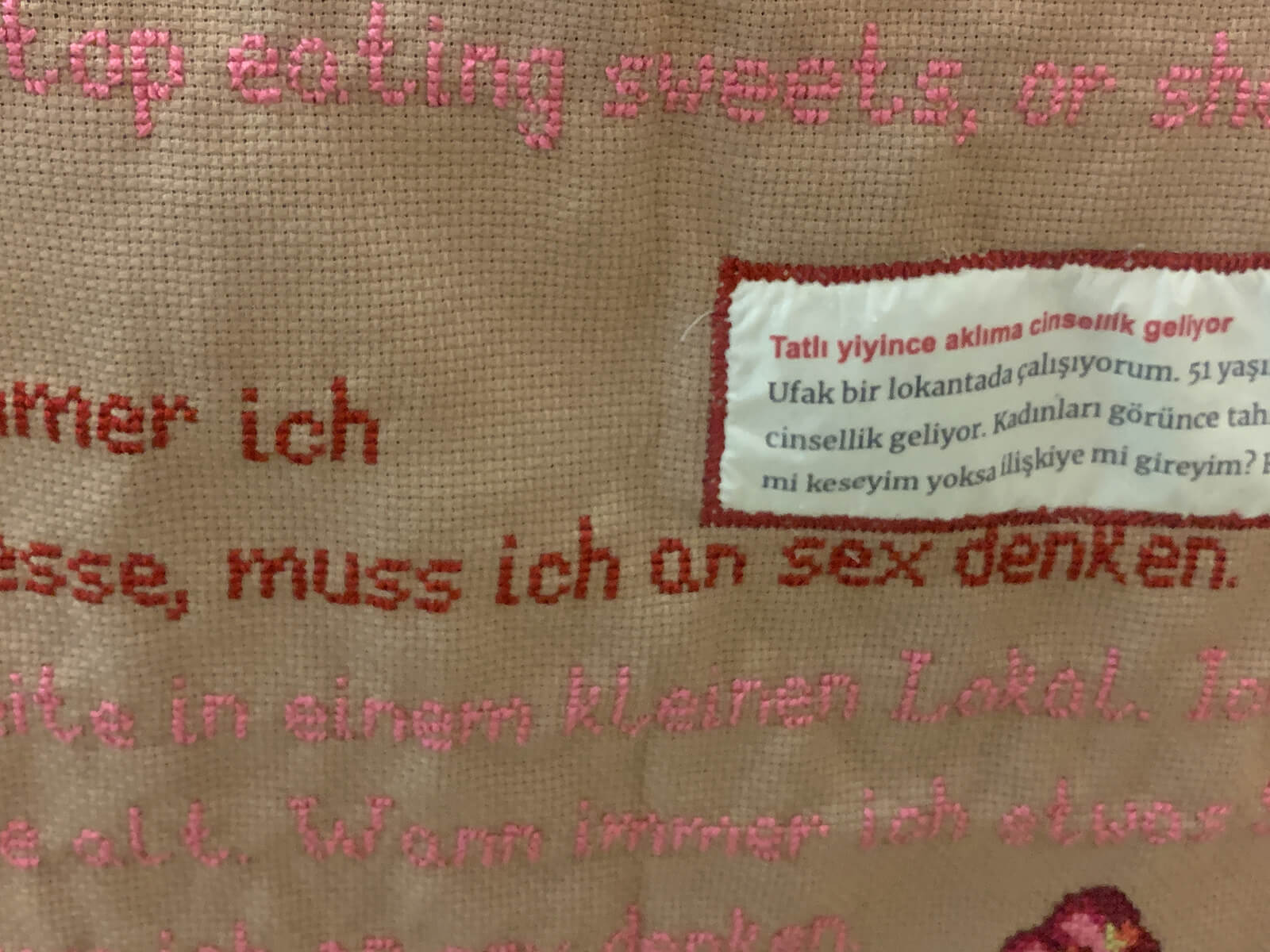

Elif Erkan: For my upcoming show, I have been using embroidery to display and contextualise letters that were written to Haydar Dümen, a Turkish sex therapist and columnist. I was intrigued by those letters, because I grew up with those that were published daily in the newspapers. They were, for me, always a reminder of what place and time I was living in as a woman, since most of those letters were written by men, yet the main readers of this paper were women. I chose embroidery as medium because embroidery has this story of keeping women’s hands busy to not think of sex and to masturbate. So, while embroidery should practise abstinence, it is highly sexual and sensual. For me, embroidery was, here, the right medium to bridge the male authors of the letters with their female reader circle.

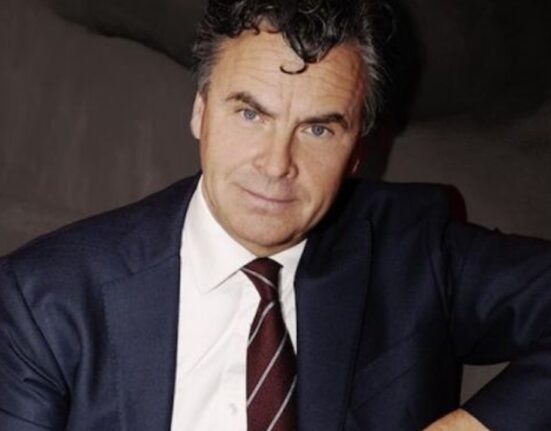

Dümen was a psychiatrist who was born 1930 in Turkey. He is one of the first psychologists to research Turkey’s relationship to sexuality. He gained attention by saying publicly in an interview that 60 per cent of Turkey’s population is bisexual: a very scandalous statement in a very heteronormative and misogynistic society. Since the 1960s, he was giving answers to readers regarding sex in his column Ask About Your Sexual Problems in various different newspapers. The most asked questions in this column centre around the thoughts “Am I normal?” or “Help me, I think I am not normal!” Dümens’ answers, though, would always be very far off from therapeutic advice. His answers would always be tinted with the current political climate and wrapped into poetic prose. The newspapers he would be writing for would be considered “yellow press”, trash. His column would be sandwiched in between gossip, crossword riddles and dietary advice.

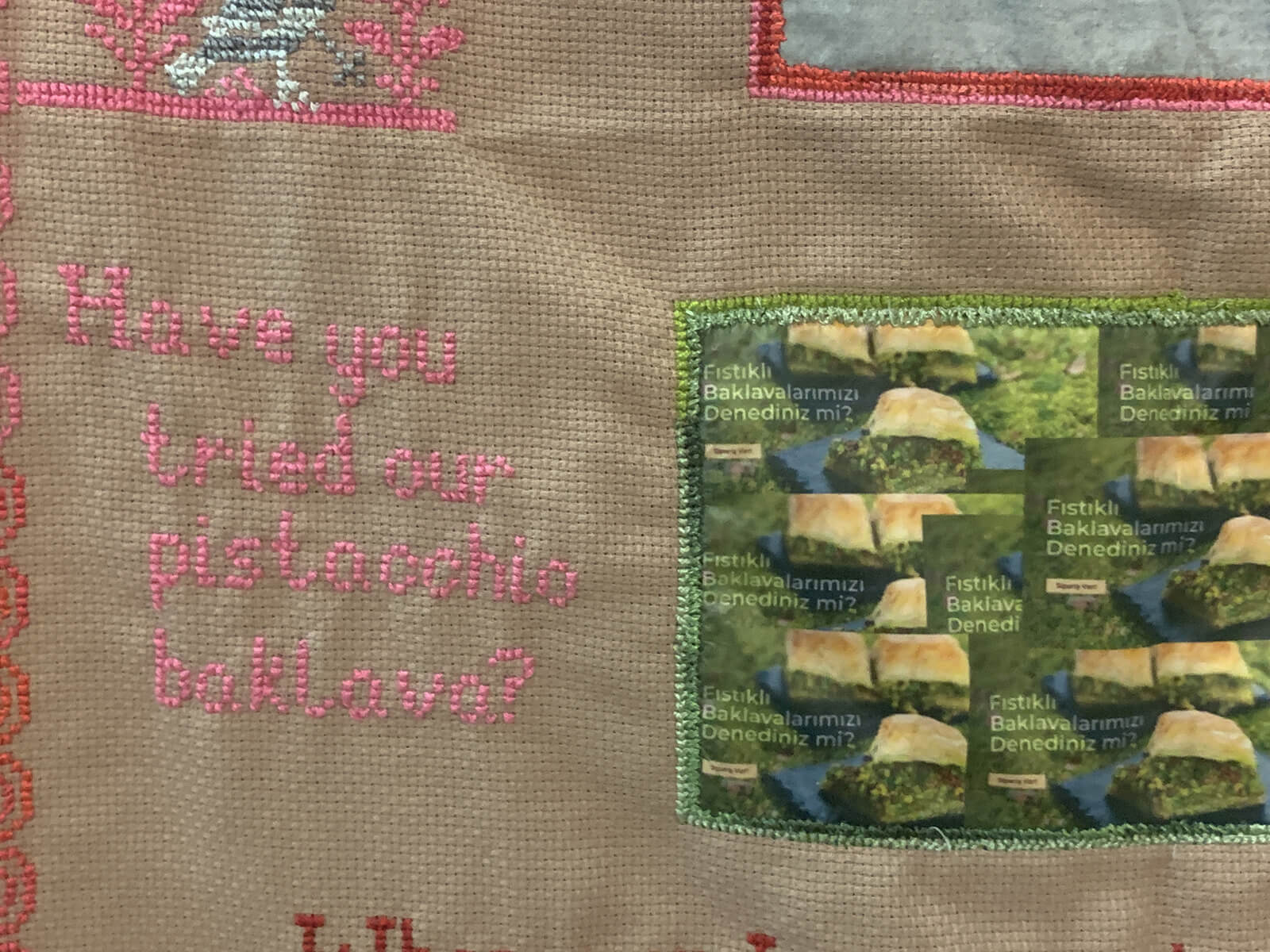

I chose to embroider the questions to Dümen that are innocent and yet concerning, especially regarding their view toward women. I use appliqué and photo transfer for the original text and embroidery for the translation. I wanted to make the art piece accessible outside Turkey and also mark the pieces as female. By referring the texts and their translations back to the stereotypical main readers of Dümen’s column (women) by using embroidery, I wanted to give an inherent critique and context without being judgmental. Also, like the column itself, the text is couched between advertisement and trivial imagery (traditional embroidery motifs).

For me, the decision to choose embroidery over painting came from the urge to work materially, soft and clean, and to double the notion that this is a weaving of the fabric of society, keeping in mind that the level of sexual education always mirrors how enlightened a society is.

Rosalyn: Do you find yourself looking at the back of your embroidery as you stitch?

Elif: Very rarely… only to fix the ends of yarn. I feel my embroidery with the tip of my index finger.

Rosalyn: How do you decide when a work should be painted and when it should be embroidered or whether to incorporate embroidery in your work?

Elif: When I look back at my textile work, it was always text-based. For me, a text is tied to a voice, and a written text is tied to a hand. Of course, painting follows a similar rule…

Rosalyn: What is your experience of time when you embroider?

Elif: Time flows differently when I embroider. Faster, yet slower. When I don’t have a watch, I completely lose track of time. I guess I get into a state of flow.

Rosalyn: Would you say that your inheritance of embroidery as a skill and a craft and your use of it as an art form has a matrilineal legacy?

Elif: Women around me in my childhood were often occupying themselves with needlework. It was around specific times of the day: after lunch or after dinner, to relax, calm down or to just keep one occupied. When I started to do needlework, it was to be part of that female circle. When I went back to do embroideries, it was mostly for me to create a quiet space and space of recreation within my home for myself. In my work, I use embroidery to highlight images that are directly tied to an individual looking for a quiet, peaceful state of mind.

Also read:

Part 1: Behind artists’ embroideries: Varunika Saraf and Nour Shantout on their process