Opulently clad in a crimson tunic, the subject of Jan Jansz Mostaert’s “Portrait of an African Man” looks pensively, even imperiously, into the distance, his cream-gloved hands clasping a sword and purse — symbols of status and wealth. Captured in oils in 1525-30, he poses hand on hip with the “Renaissance elbow”, commanding space.

Thought to be the earliest European fine-art depiction of an African man, and on loan from Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum for Black Atlantic: Power, People, Resistance at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, this precious Dutch miniature affords a glimpse of a world before the holocaust of transatlantic enslavement. By the late 17th century such “fully human” African subjects would “disappear from European fine art”, as the exhibition’s lead curator, Jake Subryan Richards, explains. Among myriad horrors and marvels, this brilliantly thought-out and unmissable show, co-curated by Victoria Avery, traces with forensic clarity how and why that loss occurred.

The Fitzwilliam’s lavish entrance hall “exemplifies in its grandeur, and perhaps its smugness, what this institution has stood for”, according to the museum’s director, Luke Syson. In a “deliberate act of disruption” — through objects held largely by eight Cambridge university museums and a botanic garden, spanning archaeology to zoology — this watershed show uncovers how pervasively this landlocked “city of learning” (and by extension Britain as a whole) was shaped by the maritime trade in captive human beings.

Syson has said in an interview that returning to head the Fitzwilliam from the Metropolitan Museum in New York four years ago gave him the distance needed for the task. Distilling decades of research, the stories told in this “profoundly evidence-based” exhibition, he says, “begin in the things we have”.

Joseph Wright’s 1764 oil painting of the founder, Richard Fitzwilliam, as a gold-gowned Cambridge graduate, appears alongside “Portrait of a Man in a Red Suit”, an oil painting of 1740-80 by an “unrecorded maker”. Until this year, the portrait was assumed to be of the black abolitionist writer Olaudah Equiano, who lived in Cambridgeshire. But nothing is really known of the sitter’s identity. Visitors are guided towards fundamental questions about who is named and who is left anonymous, what is deemed worthy of notice, record or remembrance, and the role of art and knowledge in reinforcing dehumanisation.

The seventh Viscount Fitzwilliam, whose £100,000 bequest to the university in 1816 came with an art collection, owed a significant part of his wealth and art to his slave-trading maternal grandfather, the Dutch-born Matthew Decker — a fact “never publicly acknowledged” until now, Syson says. Decker brought his knowledge of the Dutch slave trade to England in 1700. He co-founded the South Sea Company which, with state support, gained the monopoly to traffic African people to the Spanish Americas, helping “put enslavement at the heart of early British capitalism”. A 1720 portrait by Theodorus Netscher shows Decker in fine silk jacket. Beside it is Netscher’s still life — almost a portrait — of a plump pineapple from England’s first crop, planted on Decker’s Richmond estate and served to King George I.

A display on “Slavery before racism; blackness before slavery” explores the peculiarity of the transatlantic trade that transported more than 12.5mn captive Africans to the Americas between 1400 and 1900. Slavery had previously been neither racial nor necessarily inherited (a slave depicted on the plaster cast of a 400BC Greek stele is marked out by her smaller stature). White servants and convicts worked plantations too. But by 1700, British colonial laws equated slavery with blackness.

Artists and writers have long contested the incomplete histories of such collections. (Not by chance was Caryl Phillips’s 1991 novel on Caribbean slavery entitled Cambridge, after its literate freed slave.) Contemporary art appears, with immense cumulative power, beside the objects that provoked it. An 1808 fold-out of the Liverpool slave ship Brookes is shown with Keith Piper’s 14 monochrome photomontages, ironically juxtaposing such stowage plans with the 1865 catchphrase, “Go West Young Man” (1987). Using these photomontages, Piper imagines a conversation between a father and son in post-Windrush Britain amid the legacy of fear and fantasy that still paints black men as a “nexus of sex and savagery” and “brute force personified”.

Richard Waller’s ink-and-watercolour “Table of coloures” (1686), illustrating scientists’ role in justifying hereditary enslavement, appears near Keith Piper’s ironic “The Coloureds’ Codex (Enlightenment Edition)” (2023): a box with 15 pots of pigment arranged according to an arbitrary hierarchy of skin tones. Maps, globes and an 1828 marine chronometer suggest how royal and state patronage for science had an ulterior motive. The British parliament’s 1714 cash incentive to solve the problem of calculating longitude at sea was largely to aid the navigation of slave ships.

Artistic portrayals of black people shifted after the 1600s to mirror and bolster the emerging status quo. In Peter Lely’s “Elizabeth Murray, Lady Tollemach, with a Black Servant” (1651), the aristocrat’s whiteness is idealised and accentuated by her doting, unnamed servant who recedes into the background. Countering this vision, Barbara Walker embosses the outlines of white figures in old-master paintings to highlight unnamed black subjects drawn in graphite. In “Vanishing Point 29 (Duyster)” (2021), an African man in a ruff is centre stage.

Products of slavery — from mahogany to tobacco — transformed European consumption, setting fashions in luxury goods. A Liverpool punch bowl painted with galleons bears the pro-slavery inscription, “The Africa trade”. Yet mundane objects more often concealed products’ origins. A Delft tobacco jar depicts an indigenous man in Havana gifting tobacco barrels to a European merchant, veiling the subjugation involved. Fitzwilliam’s mahogany-and-silver caddies, engraved with his coat of arms, sanitised the plantation tea and sugar they held.

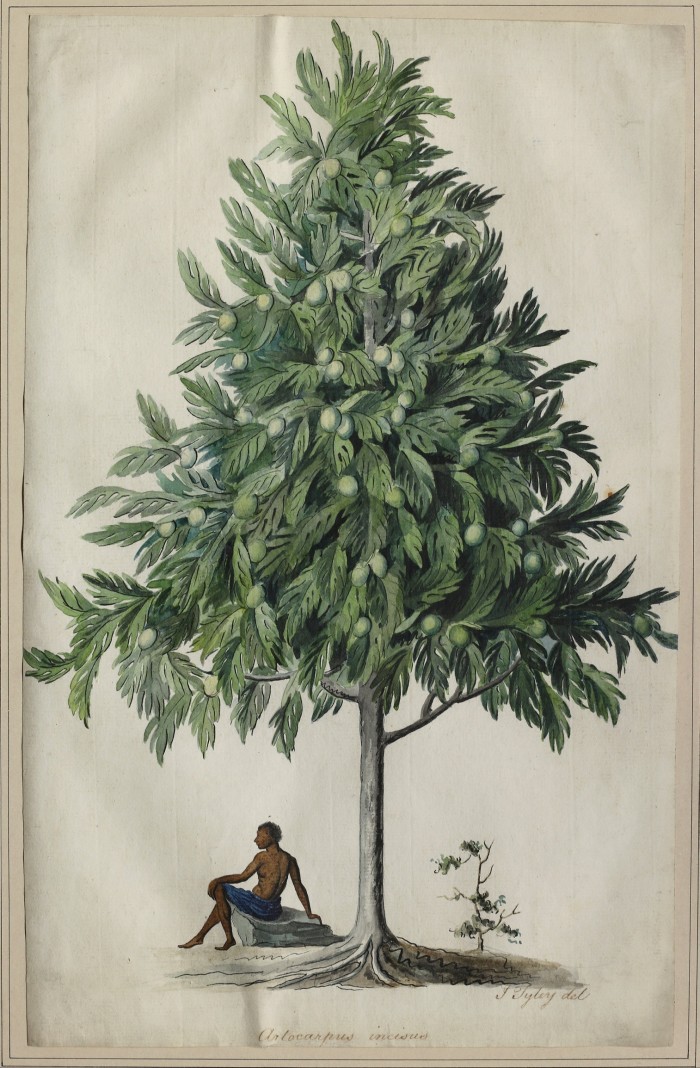

A final section on plantations highlights their role in producing scientific knowledge. Naturalists — such as John James Audubon in his book The Birds of America (1827-38) — used those who worked on plantations as uncredited sources. Maria Sibylla Merian’s 1705 drawing of a pink-toed tarantula implausibly devouring a hummingbird likely mistook as fact west African Anansi folklore. John Tyley’s watercolour of a breadfruit tree, by a rare black artist-botanist from Antigua, is exceptional in showing a plantation worker resting under it.

Landscape paintings, such as Frans Post’s pastoral idyll of a sugar mill in the 1650s, art-washed abject violence. Yet if art conceals, it can also expose. Jacqueline Bishop’s “History at the Dinner Table” (2021) responds to Captain Stedman’s illustrated journal of savagery from 1779, recording his quashing of Maroons in Suriname. The decorative beauty of Bishop’s flower-embellished bone-china service belies its horrors. In one of 18 painted plates, a red-coated overseer strings a woman up by her ankles. In another, a spreadeagled figure is flogged.

A plantation bell from Demerara, cast in 1772 to order the working day, was donated to St Catharine’s College in 1960. Removed from the college entrance in 2019, “when the direct connections to enslavement are fully understood”, it is displayed here, overturned. The oppressive, bullet-like sugar-mould sculptures from the late Donald Locke’s Plantation Series were created in London back in the 1970s. Half a century on, and partly taking its cue from such artists, this sobering show may be a revelation to many — and liberating for all. It deserves to be seen and reflected upon.

To January 7 2024. fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk