Around 1922, in his apartment at Nice, right along France’s balmy Mediterranean shore, Henri Matisse began to paint a series of odalisques — “a French term for a concubine in a harem,” explains London Royal Academy of Arts curator Ann Dumas.

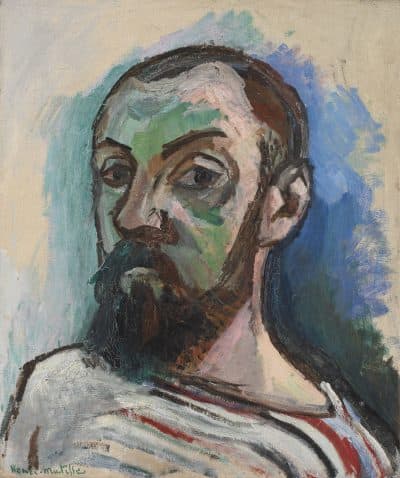

For two decades, Matisse (1869-1954) had been at the forefront of Western art, pioneering new, abstracting ways of seeing the world and methods that rethought the very nature of painting itself. He electrified paintings with bright colors. He painted faces as if they’d been bluntly chiseled out of wood. He explored cubism. He collapsed the illusion of space that had been at the center of European painting since the Renaissance, instead creating paintings that felt nearly as flat as his canvas or in which contrasting and overlapping patterns of curtains, wallpapers, upholstery and rugs confounded perceptions of depth.

These innovations had led the French artist to be considered one of the very greatest and most influential Western artists of his generation — perhaps only surpassed in the first half of the 20th century by Pablo Picasso.

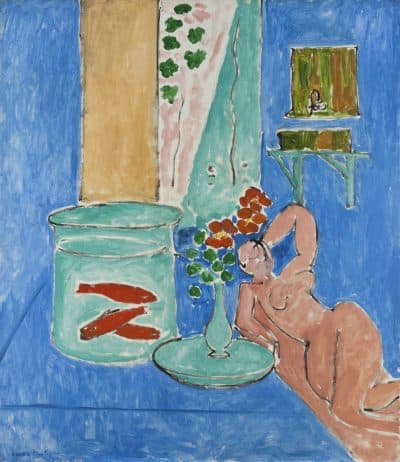

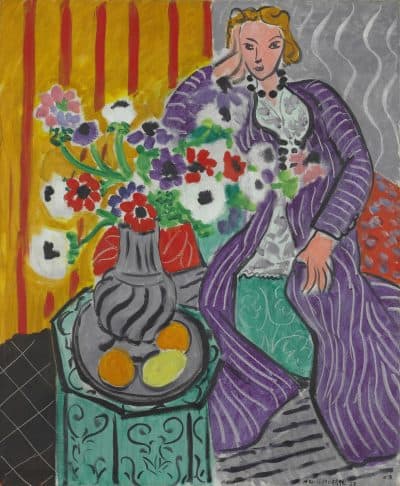

Now, for much of the 1920s, he would continue to examine the nuances of flatness and pattern, but he would do it while exploring an old European trope: the harem sex fantasy featuring imagined Muslim women from lands the French had conquered in North Africa.

In his Nice apartments, his studio setups became increasingly elaborate, with North African fabric screens called haitis and other textiles draped over ropes and a tall wooden folding frame. He used the backdrop to create a sort of alcove, furnished with a painted wood guéridon table from Algeria, a wooden octagonal chair from North Africa, an Ottoman charcoal heater called a brasero, and other studio props. In this setting, he posed white European women — primarily Henriette Darricarrère, who worked closely with Matisse from 1920 to ’27 — lounging in beaded bracelets, baggy long “harem pants,” kaftans, sheer veils, see-through blouses and dresses, and various states of undress.

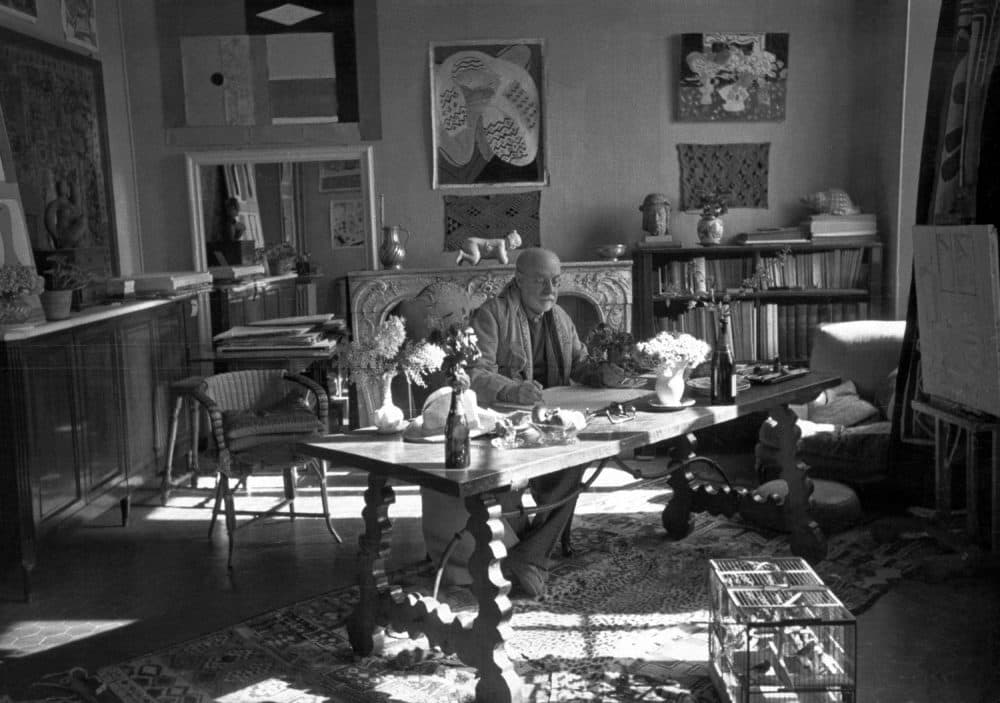

These odalisque fantasies are at the heart of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts’ major new exhibition “Matisse in the Studio,” on view from April 9 to July 9. The dazzling show reunites many of Matisse’s studio props — an 18th century French pewter jug, African masks, Chinese calligraphy, an Egyptian tent curtain, Islamic curtains and furnishings — with more than 80 of his paintings, sculptures, prints and “cut-outs” that they inspired throughout his career. Deft pairings illuminate Matisse’s methods — how much his art was focused on the interior world of his studios; how despite all his abstracting, his art was rooted in careful observation and depiction of things he saw.

“A lot of people coming to the exhibition, they’re going to be surprised to find out how culturally diverse his interests were,” says Wheaton College professor Ellen McBreen, who organized the exhibition with Dumas and MFA curator Helen Burnham. “One of the most French of French artists of the 20th century had really culturally hybrid sources. … He had this kind of endless fascination for objects and traditions outside of France.”

But that cultural interchange is complicated by that fact that much of it, as McBreen writes in the catalogue, was “made possible by larger political structures, such as colonialism, which in turn made African and North African culture accessible to Matisse in the first place. Needless to say, there would have been no West and Central African sculpture to study or collect in Paris in the early 20th century without European colonists invading those lands: African art was the spoils of this war.”

In Matisse’s art, this larger colonial context that he’s working within becomes most troubling when it’s reflected in paintings depicting European sex fantasies featuring the conquered peoples.

“You can’t really expect somebody to be part of this time, but the question is what do you do with it?” Burnham says. “It’s not my job to recuperate Matisse. My job is to be honest about what we’re seeing.”

So, if we look frankly, is it still OK to like Matisse’s harem fantasies?

‘The Emotion It Produces Upon Me’

In the fall of 1906, Matisse was walking over to visit the influential collector and writer Gertrude Stein, when the window of “a little antique shop” caught his eye. In it was a carved wooden African sculpture of “a little seated chap sticking out his tongue” (he recalled in 1941) or “a small Negro head” (as he told the story in 1951; it was a story he told repeatedly).

It reminded him of ancient Egyptian art. “I felt that the methods of writing form were the same in the two civilizations, no matter how foreign they may be to each other in every other way,” he said in 1951. “So I bought the head for a few francs and took it along to Gertrude Stein’s. There I found [the artist Pablo] Picasso, who was astonished by it. We discussed it at length, and that was the beginning of the interest we all have taken in Negro art.”

Here in this meeting in a Paris apartment is the wellspring from which so much of Western modernist art flows. As Europeans began to invent this new artistic language in the mid 19th century, they looked for new models outside the precincts of European fine art, turning to popular arts and to art made outside Europe. One strain of this produced French Orientalism — ranging from Eugene Delacroix’s 1820s and ‘30s painted imaginings of Middle East harems to Claude Monet’s 1876 painting (in the MFA’s collection) of his wife dressed up in kimono to Vincent Van Gogh’s painted copies of imported Japanese woodcut prints in the 1880s.

Matisse was after an art of feeling — “I do not literally paint the table, but the emotion it produces upon me” — and he believed he found a model in African art. He praised the “simplification” of African sculptures. “He would take a figurine in his hands, and point out to us the authentic and instinctive sculpturesque qualities, such as the marvelous workmanship, the unique sense of proportion, the supple palpitating fullness of form and equilibrium in them,” American painter Max Weber, who’d studied with Matisse in 1908, recalled in 1951. By 1908, Matisse owned some 20 African figures and masks.

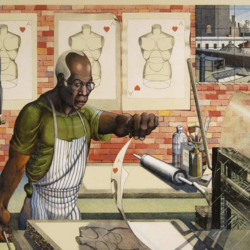

Matisse applied the formal lessons he took from African masks and sculptures to his 1906 painted “Self-Portrait,” his 1907 painting “Standing Nude” and his 1908 bronze sculpture “Two Women,” depicting two naked women standing facing each other with their arms around each others shoulders. The shapes of the faces and bodies take on characteristics of African masks — blunt and abstracted as if boldly cut from wood.

But African art wasn’t his only source of inspiration. “Standing Nude” was based on a photo of a naked (apparently) white woman “evoking the idea of surprise or modesty” that he found in an October 1906 edition of the magazine Mes Modèles. “Two Women” — sometimes called “Two Negresses” — was based on a photo of two young naked women, with their hair in tight braids, identified as “young Tuareg girls,” from the nomadic Berber people of the Sahara, in a January 1907 edition of the “ethnographic-erotic magazine” (according to the MFA) L’Humanité Féminine.

A 1907 photo shows Matisse standing in his studio with “Two Women” on a modeling stand and the source photo of “Tuareg girls” tacked to the wall behind.

The naked lady photos in Mes Modèles (My Models) were “billed for artists,” McBreen explains. “You can have this photograph and you don’t have to have a studio model. But come on.” L’Humanité Féminine (Feminine Humanity), she says, was “very poorly researched, very racist. … They’re very commercial publications.”

Looking at the sculpture, McBreen asks, “Is this his reaction to this photograph or his reaction to his feelings about women? He does make these women look much more powerful and much more sexual than the traditional artists were doing.”

“We don’t have to make peace with the politics of it because the politics are up for grabs and problematic,” McBreen says. “As Matisse is introducing new ideas about the female body, he’s also exploiting the female body at the same time.”

‘Revelation Thus Came To Me From The Orient’

“The object is an actor,” Matisse said in 1951. “A good actor can have a part in 10 different plays; an object can play a role in 10 different pictures.”

Matisse bought some of his collection of masks, textiles and other studio props while traveling, but the majority of them he acquired from shops in Paris and elsewhere in France. They became a sort of repertory company — appearing again and again in still-lives or to add ambience to posing models.

Looking for non-European models for his avant-garde aesthetics, he adventured to the (then) French colony of Algeria in 1906 and to Munich to see the landmark exhibit “Masterpieces of Mohammedan Art” in 1910. Which inspired him to visit Alhambra in Granada and the Great Mosque of Cordoba, Spain, in the winter of 1910 to ’11, and bring back an Andalusian glass vase.

“Matisse’s travel to Morocco in 1912 and 1913 was allowed by the recent establishment, just months before his arrival, of the French protectorate [there] by the Treaty of Fez,” McBreen writes in the catalogue. Matisse wrote in 1915, “What are we doing in Morocco? Teaching them to live with cannon fire!”

“If I instinctively admired the Primitives in the Louvre and then Oriental art, particularly at the extraordinary exhibition at Munich, it is because I found in them a new confirmation. Persian miniatures, for example, showed me the full possibility of my sensations,” Matisse said in 1947. “…Revelation thus came to me from the Orient.”

‘Look At These Odalisques Carefully’

In August 1914, Matisse’s hometown of Bohain-en-Vermandois, in northwestern France, fell to German troops in the early days of the First World War. With memories of looting by German forces who had occupied the town just after Matisse’s first birthday in 1871, during the brief Franco-Prussian War, his mother “buried her valuables in the back garden,” Hilary Spurling reports in her 2005 biography “Matisse the Master.”

This time, “the invaders paused just long enough to pillage the area, raiding cellars, slaughtering poultry, pigs and cattle, loading stolen cards and wagons with loot,” Spurling writes. (Germans would overrun the town again in World War II.)

The Germans had rushed through Belgium hoping to catch the French off guard and take Paris, where Matisse was with his wife. (Their kids had been sent south to a grandfather in Toulouse.) He hurriedly buried “sculpture in the garden” of his Paris residence, Spurling reports. The French army requisitioned his Issy-les-Moulineaux property in Paris’ southern suburbs for use as a headquarters. By Sept. 2, the booms of artillery could be heard in Paris as the German advance got to within 30 miles of the French capital.

While Matisse’s art often benefits from the spoils of French colonial expansion across Africa, he was also at times a victim of German territorial aspirations in France — sometimes he was among the people who had to bury their treasures in hopes of keeping marauding Europeans from making off with them.

Matisse was rejected for World War I military duty because of illness, a poor heart and age (he was now in his 40s). Instead he continued painting. He had been one of the leading figures in Western art, a pioneer of the abstracting language, for two decades now. In 1917, Matisse moved alone from Paris south to Nice, where he would spend much of the rest of his career. He moved there, Dumas says, in part, to get distance from World War I.

“I had to catch my breath, to relax and forget my worries, far from Paris,” Matisse said in 1951. “The odalisques were the fruits of happy nostalgia, of a lovely, lively dream and of the almost ecstatic, enchanted experience of those days and nights, in the incantation of the Moroccan climate. I felt an irresistible need to express that ecstasy, that divine nonchalance, in corresponding colored rhythms, the rhythms of sunny and lavish figures and colors.”

“I do odalisques in order to do nudes,” Matisse said in 1929. “But how does one do the nude without it being artificial? And then, because I know that they exist. I was in Morocco. I have seen them.” (Historians say it’s highly unlikely he had access to intimate Muslim spaces. Perhaps what Matisse was thinking of was the brothel at which he painted during visits to Morocco in 1912 and 1913.)

At first he stayed in hotels in Nice, but around 1921, he moved into a spacious apartment. There he began making his harem paintings of costumed and naked models posed in theatrical settings filled with brightly patterned North African haiti and other foreign goods.

“It took me a while to warm up to 1920s Matisse. At first glance, OK, I’m looking at a very familiar scenario. Subject matter can distract you from the ways the paintings are set up,” McBreen says. “…Not all depictions of nudes are the same. Matisse himself was like, ‘Don’t be fooled by my odalisques. There’s a torpor underneath.’”

She’s referring to what Matisse said in 1951: “Look at these odalisques carefully: the sun’s brightness reigns in a triumphal blaze, appropriating colors and forms. Now, the Oriental decors of the interiors, all the hangings and rugs, the lavish costumes, the sensuality of heavy, slumbering flesh, the blissful torpor of the faces awaiting pleasure, this whole ceremony of siesta brought to maximum intensity in the arabesque and the color must not deceive us: I have always rejected anecdote for its own sake. In this ambience of languid relaxation, beneath the sun-drenched torpor that bathes things and people, a great tension smolders, a specifically pictorial tension.”

In other words, Matisse seems to say, it’s OK to like his harem fantasies because they’re not really about the sensual flesh and North African stagings, they’re about the amazingly charged compositions.

Failing health and a botched 1941 cancer surgery that nearly killed him, left Matisse nearly bedridden for the last decade or so of his life. He painted less and less — abandoning it almost entirely around the end of World War II — and began making stunning “cut-outs” that he scissored out of paper painted in rich hues.

He cut out bright silhouettes of a sword swallower, trapeze and other circus scenes in 1943 and ’44 that were published in his 1947 book “Jazz.” Some of these prints included leafy shapes — like tropical fronds or seaweed—that evolved into major motifs of his subsequent cut-outs, like the overlapping orange, blue, yellow and black leaves in his 1951 “Mimosa.” These artworks arrive as the culminating synthesis of his interest in brilliant color, flat pattern and Islamic design.

‘Picturesque Cultural Stereotypes’

“There were so many reproaches even when I did the long series of odalisques,” Matisse said, still feeling raw, in 1951. “The charges some people made against me stuck for a long time … Did I paint too many odalisques, was I carried away by excessive enthusiasm in the happiness of creating those pictures, a happiness that swept me along like a warm ocean ground swell? I still don’t know.”

Matisse went on, “What I could not accept was that, in chiding me for a certain profusion of these pictures, people felt entitled to describe them with words like ‘exoticism’ and ‘Orientalism,’ used in the pejorative sense, as if my natural bent, my predilection for the arts of the Orient, might have drifted, given the plastic use I was making of some of their elements, might have drifted into mannerism, facile decorativeness, or even a questionable rococo!”

By painting odalisques, McBreen writes in the catalogue, “Matisse was still very much engaged with the legacy of 19th-century French Orientalism, a visual tradition that had effectively reduced the rich cultures of North African and the Middle East to a series of picturesque cultural stereotypes that, in turn helped to justify the ideology of European superiority at the heart of colonial conquest.”

So is it still OK to like Matisse’s harem fantasies?

“His theatrical set-ups in Nice seem to acknowledge the fiction, and inadequacy, of such traditions,” one of the exhibit’s signs says. “In the end, Matisse was drawn to this part of the world in an open-minded pursuit of new ideas about design and abstraction, and his artistic appropriations from North African objects helped him innovate beyond the confines of European tradition.”

McBreen writes, “When the gender and cultural dynamics of work from this period are read literally — as a rehash of the passive odalisque who exists only to be ogled, or as an attempt to transport viewers to North Africa — the complexity of the formal experimentation behind the world of false perspectives and misleading masquerades is lost.”

“Should we just ignore that this is a major part of modern art or should we show that this is where it comes from?” Burnham asks. “It’s up to visitors to figure out if they’re OK with that or if they’re disturbed. I think it helps to see that it’s part of the process of his art.”