View of The European Fine Art Fair in Maastricht, Holland. (Photo credit: S. Karabell)

S. Karabell

The Art Market Report, issued by The European Fine Art Fair (TEFAF) each year during its 10-day March event in Maastricht, Holland, is something of a bible for costs and trends in the world’s art market. So when, this year, the widely accepted and TEFAF-promulgated $60-something-billion market size was replaced by a $40-something-billion dollar price tag, collectors and journalists alike gave a collective gasp.

Indeed, the market had softened a bit since last year (TEFAF called it a shifting market, rather than a shrinking market), but the real reason for the $20 billion+ difference was a change in the metrics used in measuring the art market by the new economist and report author – Maastricht University professor of art market & finance Rachel Pownall, in place of art economist Claire McAndrew (now with the competing Art Basel fair) who had used her own metrics since starting the report back in 2002.

What Is A “Gallery?”

Pownall apparently uses a much tougher definition of “galleries,” to start. While McAndrew had included nearly 70,000 in her sample, Pownall included a more exclusive 21,000. “We focused more on only those dealers who handle exclusively arts and antiques and did not include second-hand retailers,” she told me in a reply to my questions from the floor following her presentation at TEFAF. Pownall says that while her numbers for the overall art market may be smaller than McAndrew’s, they are more representative of the true global market. And indeed, despite the difference in metrics and resulting numbers, Pownall’s report claims the overall art market inched up by nearly 1.7% from 2015-2016.

The monetary value of the market is also dependent upon who sold what and where. “So, what is a ‘collectible’? If it’s something sold by an antique dealer, then OK, we included the sale; if it’s sold at a second hand shop or a flea market, the sale was not included in the numbers,” she explained. Auction numbers were provided by ArtNet.com; statistics on dealers were collected from offices of national statistics worldwide.

But even this re-definition of “galleries” takes some honing. The scene is dominated by a handful of huge players and then a series of small proprietors. “The dealer market is not normally distributed,” Pownall’s boss, Jaap Bos, Chair of the Finance Department at Maastricht University, told me following the presentation. “There are some really big players and then the rest (note: nearly 75% of the world’s gallery market are sole proprietors). So contributions from dealers are weighted differently (according to size), and that brings down the total value. In the past, the report assumed more big players (bringing in more money) than there really are.” Using these new metrics, in an art market whose total value last year was $45-billion, dealers accounted for $25-billion, more than half of the income.

Economics is an inexact science. But there were nevertheless some distinct and exacting trends in the art market in the past year.

Auction Sales Decline

Worldwide, auction house sales dropped 18.8% year over year, to $16.9 billion. This was partially due to a significant drop in prices for the traditional big-sellers such as Picasso (down 50%) and Andy Warhol (down 68%). Foreign exchange – namely the huge decline in value of the British Pound – accounted for some of the drop. The number of items sold at auction last year also fell – by 21.5%.

Private sales by dealers, however, increased in value by as much as 25% year on year, accounting for some 70% of all sales worldwide. Europe is home to 54% of the worldwide dealer community, according to the report, and saw an increase of 20% from 2015-2016. The report suggests the shift from public auction to private sales is due to an increased desire for privacy on the part of buyers – something you don’t get at auctions houses where transparency is mandated by law. But it is still auction house sales that set pricing benchmarks –even for private sales.

“Uncertainty is very high,” says AXA Art Global CEO Kai Kuklinski of buyer behavior in the art market today, explaining one reason for an apparent desire for transactional privacy. AXA Art is TEFAF’s principal sponsor. He suggests global political and financial uncertainty is behind it all. “People are just waiting to see what’s going to happen. They are bringing possessions abroad, working out issues related to taxation, but also looking to diversify their portfolios (with art as an asset class),” he continues, adding that he sees an increase in the number of people wanting to insure jewelry and precious metals – traditional signs of hedging uncertainty. “But uncertainty is often a good thing for insurers,” he adds with a smile.

Model for official bust of Louis XVI (c. 1781), offered for sale at TEFAF by Didier Aaron, Inc, NYC.… [+]

Dealer Herve Aaron, a Paris-New York gallery dealer, believes that part of the reason private sales are increasing is financial. “Even auction houses are doing more private sales than they did last year,” he told me in an interview for this blog at his TEFAF installation. “Private sales are more lucrative, and it’s true that serious collectors often prefer privacy.” The TEFAF report concurs, pointing out that some private sales “go unreported into tax havens,” or remain in Freeports – a kind of un-taxable, secure no man’s land.

Paintings accounted for 70% of art market global sales, followed by sculptures, antiques, collector pieces and prints. Vivian Ebersman, Director of Art Expertise at AXA Art, has been watching what collectors buy for the past 18 years. “When I started, Impressionists were the most expensive thing you could buy,” she told me in an interview for this blog. “Today, new collectors are not really interested in Impressionists. I don’t see people collecting porcelain or decorative arts or antique English furniture. The market is strong for contemporary and emerging artists.”

But the biggest trend was more like a paradigm shift: the predominance of the Internet. Not just as a sales platform, but as a source of research for buyers and sellers alike – whether the sellers be auction houses or dealers. Even TEFAF – the granddaddy of art fairs and not the first to embrace cutting edge change – brought onboard as a Marquee Sponsor this year a company called Invaluable, which bills itself as “the world’s leading online marketplace for fine art, antiques and collectibles.” Founded in 1989 as a database called Art Fact, the company has morphed into an online powerhouse with more than 4000 auction houses (including Sotheby’s and Philip’s) and dealers in its stable, and buyers in more than 180 countries. Its online auction revenues increased 30% year on year, according to company statements.

Internet At The Crossroads

Invaluable’s growth and evolution show the evolution of the Internet in the art world, now sitting importantly at the crossroads of buyer and seller, serving both the demand and the supply side of the art market. “We started around the auction world,” Invaluable CEO Rob Weisberg told me in an interview at TEFAF for this blog. “Prospective new buyers wanted more information about an artist or price or background on a particular piece of art. But today consumers demand more; it’s not enough just to learn about a piece. On Amazon you buy today and it’s delivered tomorrow. The art world has been slow to respond to this sort of thing, but most are beginning to accept that this is the way the world is going.” And, he adds, 41% of his business is mobile.

The President & CEO of AXA Art Americas, Christiane Fischer, has already launched an Internet insurance product for young and emerging collectors – no easy feat in the US, where it can take 18 months to receive operating approval in all 50 states. The product started two years ago for brokers and segued directly to clients in 2016. “The next generation has different buying habits,” Fischer told me at the AXA Lounge at TEFAF. “One day we will have an app that will allow you to add automatically a new piece to your coverage, from your mobile device. The younger generation is used to doing everything online; they wouldn’t call a dealer for an insurance product.” Internet sales so far are at the low end of the price range; Fischer says, “This is low insurance revenue, but it’s also low cost to manage.”

TEFAF itself is focusing on the Internet with a full-blown report due out in the spring, to coincide with its Spring New York show at the Armory in Manhattan.

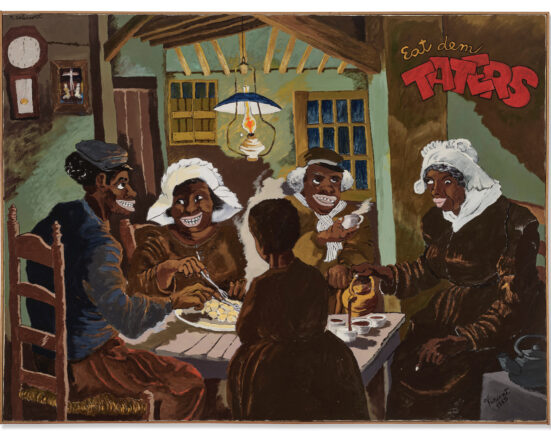

“Femme rose sur fond rouge” by Kees van Dongen (1909), offered by Ivo Bouwman gallery at TEFAF.… [+]

“The arrival of the Internet has changed the art market,” moans Ivo Bouwman who has spent 45 years working with Dutch private collectors as a gallery owner in The Hague. He told me, “People visit galleries less because they can follow you on your website. But they do come to art fairs – the number of art fairs has become staggering!” He suggests that TEFAF hold its Maastricht event (attracting 282 art and antiques dealers from some 21 countries this year alone) as a biennale and hold opposite year fairs in Asia. “Singapore would be a good place,” he opines. “It’s a Freeport and there are no customs issues as you would have in Beijing or Hong Kong. If TEFAF were biennial, people might look forward to it more. A year passes by so quickly!”